Back to work? Not without a check-in app, immunity passport

Source:Reuters Published: 2020/7/6 17:33:40

A staff member checks a visitor's ticket to enter the Universal Studios Singapore theme park on the resort island of Sentosa in Singapore on Friday, as the attraction reopened after being temporarily closed due to concerns about COVID-19. Photo: AFP

To go anywhere in Singapore these days, Joni Sng needs mobile phone apps and other technologies: a QR code to enter shops, a digital map to see how crowded a mall or park is, and a tracker to show if she was near someone infected with the coronavirus.

For the roughly 5.6 million people in Singapore, these actions are routine as the government eases restrictions placed to contain the spread of the disease. "The apps are quite convenient and easy to use, and I feel a little safer knowing that everyone else is also using them," Sng, a videographer, told Reuters.

"It has become very natural to click on the apps while going somewhere, just like wearing a mask," she said.

Singapore, along with South Korea and China, was quick to embrace technology to map the coronavirus outbreak early on with contact tracing, robots and drones.

Now, countries and businesses are mandating technologies as people return to work and begin to travel, with apps, scanners, check-in systems, and so-called immunity passports.

These are particularly needed in big cities that tend to be more densely populated, with more points of contact for the population, ranging from public transit to bars and restaurants.

"As Singapore restarts its economy, data-driven tech solutions will play a crucial role in helping the nation safely and successfully get back on its feet," Singapore's Government Technology Agency said in a statement on June 22.

Harm's way

COVID-19, the illness caused by the new coronavirus, has infected more than 10 million people worldwide and killed more than 500,000, pushing governments and companies to innovate quickly on everything from quarantines to ventilators.

Many have turned to technologies based on big data, such as facial recognition software, that have raised fears of surveillance and privacy risks, but which authorities say are needed to track the disease and keep people safe.

China's health code app was among the first off the block, showing whether a user is symptom-free in order to take the subway or check into a hotel.

In India, authorities have made the contact-tracing mobile app Aarogya Setu mandatory for everything from taking public transit and boarding flights to going to work. But these tools exclude vulnerable and marginalized populations, including those without smartphones, said Malavika Jayaram, executive director of the Digital Asia Hub think tank.

"When tools that are supposedly enabling exclude those without the right devices, the same technology that opens doors for some, closes them for others, and can serve as a barrier, not a leveler," she said.

"This raises the risk of the digital divide turning into a new sort of 'privacy divide,'" she said.

"Those with new smartphones can stay safe, remain social and return to a semblance of normal life. Those with feature phones will be barred from spaces and activities, or be unduly surveilled in order to participate in society."

In some cases, lives are at stake.

Dozens of people are stranded between warring groups in eastern Ukraine because the government requires them to download a coronavirus tracking app, and is denying entry to anyone who doesn't have a smartphone, according to Human Rights Watch.

"People have had to camp out, in some cases overnight, in the middle of an active military conflict, just because they didn't have a smartphone to download an app," said Laura Mills, a researcher at the advocacy group.

"This highly invasive app is clearly putting people... further in harm's way," she said.

Not fair

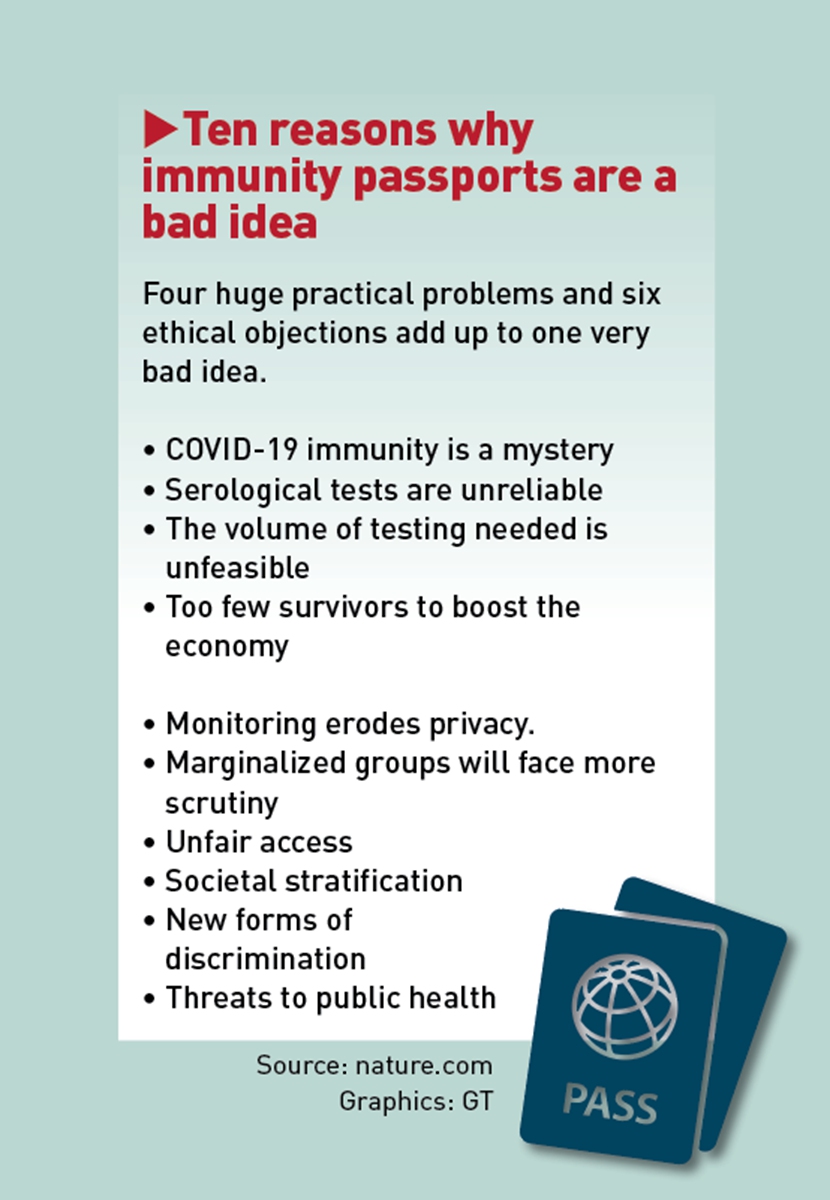

The debate around fairness and equity is set to intensify, with growing concerns that as workplaces open and international travel resumes, workers and travelers may be required to provide proof of immunity as a condition of entry.

One of the options being considered is an immunity passport, which collects testing data and enables people to share their immunity status with an employer or airline.

Estonia has started to test one of the world's first digital immunity passports, with countries including Chile, Germany, Italy, Britain and the United States also said to be exploring the option.

The World Health Organization has been quick to discredit immunity passports and the notion that the presence of antibodies in a previously infected person makes them immune.

"There is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an immunity passport or risk-free certificate," the WHO said in April. But that has not stopped firms from diving in: UK-based tech firm VST Enterprises said it has started shipping its digital health passport, COVI-Pass, to companies and governments in more than 15 countries including France, Canada and India.

IDnow, a German technology firm, has said it is in talks with the UK government for immunity passports.

Firms are also developing their own systems including Bluetooth-enabled devices, and using artificial intelligence to track employees' movements and social distancing.

Indonesia is considering an immunity or vaccination certificate, said Djarot Andaru, a researcher at the University of Indonesia who is advising the government on air transport protocol as travel restrictions are lifted. "The worry is that the tests are expensive and not widely available, so not everyone can access or afford them. That may lead to greater hardship and also fake certificates," he said.

Newspaper headline: ‘Privacy divide’ risked

Posted in: ASIA-PACIFIC