West overlooks contribution of China to regional water resource

By Hu Yuwei Source: Global Times Published: 2020/7/15 20:53:40

A fisherwoman walks on an embankment on October 31, 2019, on the Mekong River in Pak Chom district in Thailand during the drought. Photo: AFP

The New York Times cited a so-called study from US climate observers Alan Basist and Claude Williams on April 13 to blame China of limiting the Mekong River's flow that caused the record low water levels in downstream countries.

However, Chinese experts carefully evaluated Basist' report and found that both the humidity model and flow model used in the report had serious errors, resulting in unreliable and misleading results.

The review also noted the report, called Monitoring the Quantity of Water Flowing Through the Upper Mekong Basin Under Natural (Unimpeded Conditions), was not complied by any authorized academic institution, and was not published by any official or peer-reviewed publication.

Moreover, Chinese researchers found the original report's use of humidity as a representation for water flow was academically problematic. There may be a correlation between the data of station water level quoted by the original report's author and the watershed moisture age, but this correlation is not necessarily causal, so the correlation may be unstable.

Chinese reviewers suggest the water levels at the sites US observers tested may be correlated with local catchment levels, and not necessarily cause-and-effect.

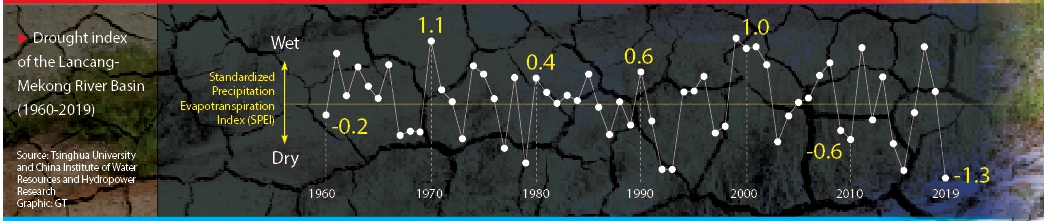

Graphics: GT

This was not the first time Western scholars attacked China's role and infrastructures' impact on LMRB countries.

In 2017, Brian Eyler, a Senior Fellow and Director of Stimson's Southeast Asia program - a Washington-based think tank - in his book Last Days of the Mighty Mekong (Asian Arguments), arbitrarily blamed China's hydropower development for a plethora of issues along the Mekong River ranging from the loss of grapes to the loss of tourists, and from villagers' dissatisfaction with relocation compensation to drought, unstable water supply and garbage accumulation.

But in fact, these conclusions based on partial evidence and unreliable analytical methods show how some Western institutions and media deliberately conceal and deny China's efforts to allocate water resources to downstream countries.

A strong El Niño in 2016 caused a once-in-a-century drought in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam, threatening 30 percent of the 1.15 million hectares of winter and spring crops. In response to a request from the Vietnamese government to increase the flow of water downstream to alleviate the drought, China's Jinghong hydropower station at Lancang River immediately released water to downstream countries.

Chinese stations along the Lancang River provided 2.7 billion cubic meters of water downstream in 2016, largely alleviating the serious drought.

Posted in: IN-DEPTH