Central banks flex their green muscle for climate fight

Source: Reuters Published: 2020/10/29 18:33:41

Central bankers fighting to save the global economy from the coronavirus fallout are preparing to deploy their firepower in another unprecedented battle - against climate change.

The wildfires, floods and droughts that ravaged large parts of the Earth in 2020 were reminders that COVID-19 is not the only crisis damaging the world economy. Such climate-driven events increasingly affect inflation, economic growth and financial stability.

Here is why central banks are getting involved and what they can do:

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a group comprising of 74 central banks as members and regulators including all the largest ones with the exception of the US Federal Reserve, argues that climate change, as a source of financial risk, falls squarely within central bank mandates.

Banks and financial companies that lend against or insure assets such as buildings in Italy's lagoon city Venice or oil refineries could face major future losses.

A 2017 study funded by the German government warned of up to $20 trillion in assets risk becoming "stranded" - effectively worthless - by 2050 as the world weans itself off fossil fuels.

Separately, the Carbon Disclosure Project, a UK-headquartered non-profit, estimates that the world's 500 largest companies are exposed to nearly $1 trillion in climate risk.

It all leaves markets vulnerable to what the Bank for International Settlements dubs a "green swan" crisis - similar to the 2008 meltdown stemming from banks' exposure to subprime mortgages.

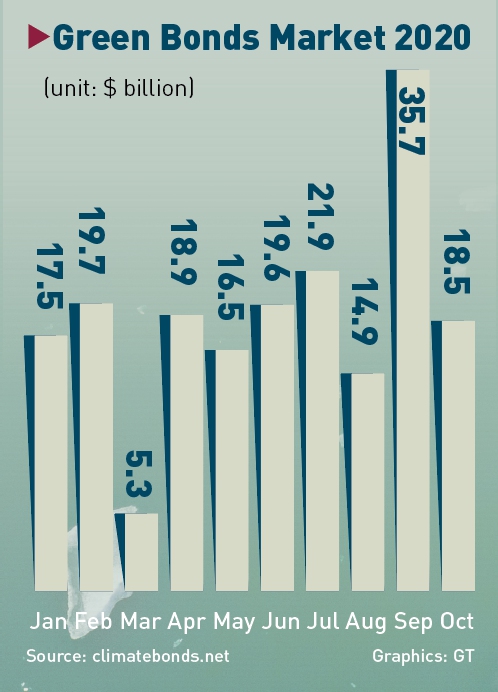

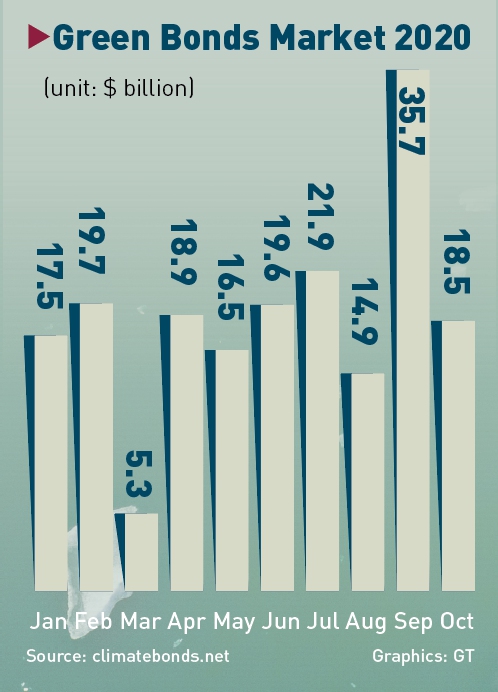

Central banks are increasing purchases of green bonds - used to finance clean energy and environmental projects - with proceeds earmarked for sustainable projects.

The ECB already owns 20 percent of eligible euro-denominated green debt, having only started buying corporate bonds in 2016. But ironically, polluting oil, energy and mining firms have received a boost from central banks via lower borrowing costs and inclusion in asset-purchase schemes.

This has prompted calls by the likes of Greenpeace for so-called green quantitative easing to ensure that stimulus doesn't fund projects harming the environment. Many at the ECB, including Lagarde, back favoring "green" debt in corporate bond-buying schemes. Some deem this a radical move as it would ditch the market neutrality principle that currently requires the ECB to buy bonds strictly in proportion to outstanding totals.

Elsewhere, the Bank of England and the Dutch central bank are including climate among criteria for bank stress tests while China's central bank accepts some green bonds as collateral.

The normally reticent Bank of Japan is stepping up too, with Governor Haruhiko Kuroda recently listing climate change among the biggest challenges facing the world economy. And Sweden's Riksbank said in November 2019 it sold off the bonds of some Australian and Canadian provinces with high greenhouse gas emissions, showing that central banks' $10 trillion-plus in reserves may prove a potent tool in the climate fight.

Purchasing green bonds, whether for stimulus or for currency reserves, sounds like the easiest option, except that the market is tiny, comprising just 4 percent of the $260 trillion global bond universe.

While that market grows, a plausible alternative is "green TLTROs" - offering banks cheaper central bank loans on condition that the money is lent on to climate-friendly companies and projects. Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) are the ECB's funding mechanism for banks.

Another approach, floated by ECB board member Isabel Schnabel in September, involves changing central banks' lending operations to make the bonds of polluting companies less valuable as collateral than cleaner peers.

Climate conscious

Stress-testing the financial sector for climate risk is gaining popularity of 33 central banks surveyed in 2020 by think tank OMFIF and accountants Mazars, 15 percent were working on such exercises and nearly 80 percent said they intended to do so.

Singapore - much of it just 15 meters above sea level - is even evaluating the resilience of its foreign exchange reserves under a range of climate scenarios.

Ceres, a sustainability nonprofit, said in a recent study the Fed and other regulators needed to ensure the financial sector took climate into account while assessing stability risks.

Climate activists also call for "brown penalizing" measures such as raising banks' capital requirements when lending to carbon-intensive firms. That would reduce climate exposure and encourage lending to lower-carbon businesses. "For me it comes down to regulation," Veena Ramani, one of the authors behind the Ceres study said.

Newspaper headline: Sustainable bonds

The wildfires, floods and droughts that ravaged large parts of the Earth in 2020 were reminders that COVID-19 is not the only crisis damaging the world economy. Such climate-driven events increasingly affect inflation, economic growth and financial stability.

Reindeers from the Vilhelmina Norra Sameby, are pictured at their winter season location on February 4, near Ornskoldsvik in northern Sweden. Photos: VCG

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde indicated in October that policymakers were up for the task, saying the ECB may need to address climate risks via its stimulus programs and other policies.Here is why central banks are getting involved and what they can do:

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a group comprising of 74 central banks as members and regulators including all the largest ones with the exception of the US Federal Reserve, argues that climate change, as a source of financial risk, falls squarely within central bank mandates.

Banks and financial companies that lend against or insure assets such as buildings in Italy's lagoon city Venice or oil refineries could face major future losses.

A 2017 study funded by the German government warned of up to $20 trillion in assets risk becoming "stranded" - effectively worthless - by 2050 as the world weans itself off fossil fuels.

Separately, the Carbon Disclosure Project, a UK-headquartered non-profit, estimates that the world's 500 largest companies are exposed to nearly $1 trillion in climate risk.

It all leaves markets vulnerable to what the Bank for International Settlements dubs a "green swan" crisis - similar to the 2008 meltdown stemming from banks' exposure to subprime mortgages.

Aerial photos showcase the stunning landscape conjured up by Iceland's glaciers.

Quantitative greening?Central banks are increasing purchases of green bonds - used to finance clean energy and environmental projects - with proceeds earmarked for sustainable projects.

The ECB already owns 20 percent of eligible euro-denominated green debt, having only started buying corporate bonds in 2016. But ironically, polluting oil, energy and mining firms have received a boost from central banks via lower borrowing costs and inclusion in asset-purchase schemes.

This has prompted calls by the likes of Greenpeace for so-called green quantitative easing to ensure that stimulus doesn't fund projects harming the environment. Many at the ECB, including Lagarde, back favoring "green" debt in corporate bond-buying schemes. Some deem this a radical move as it would ditch the market neutrality principle that currently requires the ECB to buy bonds strictly in proportion to outstanding totals.

Elsewhere, the Bank of England and the Dutch central bank are including climate among criteria for bank stress tests while China's central bank accepts some green bonds as collateral.

The normally reticent Bank of Japan is stepping up too, with Governor Haruhiko Kuroda recently listing climate change among the biggest challenges facing the world economy. And Sweden's Riksbank said in November 2019 it sold off the bonds of some Australian and Canadian provinces with high greenhouse gas emissions, showing that central banks' $10 trillion-plus in reserves may prove a potent tool in the climate fight.

A drone photo shows a flock of flamingos and other waterfowl in the shrinking Lake Van as water level decreased due to global warming in Edremit district of Van Province, Turkey on September 1.

Collateral cleanupPurchasing green bonds, whether for stimulus or for currency reserves, sounds like the easiest option, except that the market is tiny, comprising just 4 percent of the $260 trillion global bond universe.

While that market grows, a plausible alternative is "green TLTROs" - offering banks cheaper central bank loans on condition that the money is lent on to climate-friendly companies and projects. Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) are the ECB's funding mechanism for banks.

Another approach, floated by ECB board member Isabel Schnabel in September, involves changing central banks' lending operations to make the bonds of polluting companies less valuable as collateral than cleaner peers.

Climate conscious

Stress-testing the financial sector for climate risk is gaining popularity of 33 central banks surveyed in 2020 by think tank OMFIF and accountants Mazars, 15 percent were working on such exercises and nearly 80 percent said they intended to do so.

Singapore - much of it just 15 meters above sea level - is even evaluating the resilience of its foreign exchange reserves under a range of climate scenarios.

Ceres, a sustainability nonprofit, said in a recent study the Fed and other regulators needed to ensure the financial sector took climate into account while assessing stability risks.

Climate activists also call for "brown penalizing" measures such as raising banks' capital requirements when lending to carbon-intensive firms. That would reduce climate exposure and encourage lending to lower-carbon businesses. "For me it comes down to regulation," Veena Ramani, one of the authors behind the Ceres study said.

Newspaper headline: Sustainable bonds

Posted in: CROSS-BORDERS,WORLD FOCUS