When Shanghai's tycoons stood tall

They started with bags of flour and boxes of matches but went on to be some of Shanghai's richest and most successful men in the 1920s and 1930s. They led the way for the thousands of entrepreneurs who would follow them many years later and their achievements and techniques are still discussed at business schools throughout the country.

In 1921, the Rong brothers, Rong Zongjing and Rong Desheng, shone in the golden days of the flour and cotton trade. Their 14 flour mills across China churned out 250,000 kilograms of flour every day, a third of all the flour produced in China at that time. Their cotton factories turned out 30 percent of all the cotton made in China. Rong Zongjing, the older brother, once commented proudly, "If you think of food and clothing, I own half of China."

In an age that celebrated industrial heroes, the Rong brothers were true giants. They did not invent the machinery that mass produced flour or cotton, or the assembly lines that made this possible, but they were instrumental in building national industries that had been dominated by imports before they arrived.

Aggressive dealer

Hailing from Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, the two brothers were quite different. Rong Zongjing, the older brother, had bushy eyebrows and deep-set eyes. He was adventurous and bold and extremely aggressive in his business dealings. He expressed his business philosophy in this way: "If someone is willing to lend me the money, I'll borrow it. If anyone has a factory to sell, I'll buy it."

His younger brother, on the contrary, was discreet and cautious, and with a kindly, mild appearance. The brothers and partners complemented each other with the older brother focusing on business expansion, and the younger brother on management and technical development.

They started building their industrial empire in 1902. Then aged 29 and 27, they opened a small flour mill in Wuxi with the profits they had made from a small bank they owned in Shanghai. In the beginning, the factory employed 30 workers and produced 7,500 kilograms of flour every day.

At that time there were only four mechanized flour mills in China. While most Chinese people then used traditional stone milling to grind their grain into flour, the wealthy purchased imported flour from Europe and the US.

The brothers' first big break came in 1905, when the board of the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce called for a boycott of American goods, after reports of Chinese laborers suffering discrimination and abuse in the US. This was a big opportunity for China's national flour industry. The Rong brothers made a huge 60,000 yinyuan (or silver dollar) profit in the first year of production.

In 1912, they opened their second flour mill in Shanghai beside Suzhou Creek, naming it the Foh Sing Flour Mill.

In 1914 things changed. Until the outbreak of World War I, China had mostly been a flour importing country, but the war in Europe caused food shortages and exports to China dropped. From 1914 to 1915, flour imports fell from 132,870 tons to 10,281 tons. At the same time the demand for flour in Europe meant that China began exporting there. This soared over the years from 12,000 tons in 1915 to more than 121,000 tons a year from 1918 on.

Rapid expansion

This stimulated wheat and flour production in China and the Rong's flour business expanded rapidly. From 1912 to 1921, the Rong brothers built seven flour mills and leased another six in Shanghai, Wuxi, Hankou and Guangzhou to meet the growing demand for exports. The productivity of the first Foh Sing flour mill increased from 6,125 tons to 41,500 tons in 1918. By the early 1920s, they owned 301 rollermills, each with an average daily production of 1,900 tons - 31.4 percent of all China's flour production.

Their famous Binchuan brand flour was popular in Britain and France. At the 1926 Philadelphia World's Fair it won the second prize in the agricultural produce section and it was the first-ever registered trademark in China.

At home they were noted for their promotions. The company hid copper coins in random bags of flour and customers thought themselves very lucky if they found one of these.

In 1915 the Rong brothers opened their Sung Sing Textile Company in Shanghai and by 1922, they had established another three factories. Collectively, the Rong's flour and cotton businesses ranked second of China's national industries then, next only to the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company.

While their success was largely due to their personal qualities, the opening up of Shanghai's ports had enabled them to grasp the importance of modern technology and management.

Today, you can still find the buildings of the Foh Sing flour mill along the banks of Suzhou Creek. Now a retail center, the tall red brick buildings, with large windows stand silently at 423-433 Guangfu Road in Putuo district. Gone are the busy assembly lines, buzzing machines, hardworking employees and chimneys emitting clouds of smoke, but the lessons of the Rong's flour mills are still taught in business classes today.

Ambitions revealed

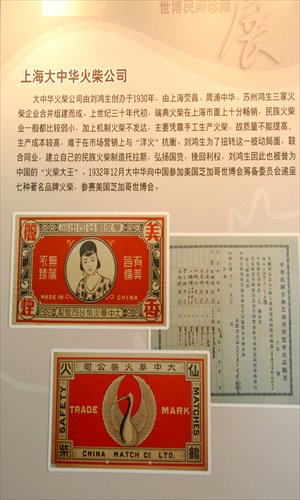

On September 20, 1932, in a letter to his sons studying in Britain, 44-year-old Liu Hongsheng revealed his ambitions. "I'm focusing all my energies on creating a national joint venture in the match industry. My ultimate plan is to merge all the match factories and relevant companies into a conglomerate, and turn this into a huge national business. I'm not being selfish. Only in this way will China's national industry be developed and protected."

This was 12 years after the Ningbo-born Liu had founded the Suzhou Hongsheng Match Company. At Shanghai's Fanhangdu Club, where he was a regular visitor, people called him "the King of Matches." To some extent, by then Liu's dream of building a match empire had already come true. But that wasn't enough for him.

Matches were an important daily necessity for every household in China. For a long time, the ever reliable Swedish matches were the best-selling matches in China. In 1929, 27 Swedish match brands suddenly lowered their prices to half the manufacturing cost in the Chinese market, trying to dominate the market by undercutting. As a result, the sales of Chinese matches plummeted and many Chinese match factories were forced to close.

Liu was concerned about the livelihood of the more than 100,000 workers in the match industry in China. He proposed a way that China's match companies could survive. He wanted them to merge into a larger company to ease the competition between national brands and attract more investment. In 1928 he tried to talk to two of the large match companies, the Chonghua Match Company and the Yingchang Match Company, but neither responded.

In November 1929, in an attempt to counter the Swedish matches, 52 Chinese match companies sent representatives to Shanghai to discuss ways to save the industry. They established a match consortium and Liu was made the chairman.

Liu again talked to the two major match manufacturers, emphasizing that he had no personal interest in creating a joint venture. He gave six reasons as to why a conglomerate was needed including that this would pool resources, save commission fees and could result in enough funds to employ scientific experts to improve the quality of their product and make it competitive with the imported matches. This time the two big companies agreed and in 1930 they and the consortium formed the China Match Co, with assets of 1.9 million yinyuan. As one of the 11 board members and the man who had initiated the merger, Liu became the company's general manager.

That was just his first step. Liu's plan was to merge as many big companies as possible and to buy out or lease smaller firms and over the next four years he continued to do this. By 1934, China Match Co had match companies in Suzhou, Shanghai, Zhenjiang, Jiujiang, Hankou and Hangzhou and produced 52 match brands - it was a giant in China's match industry.

In production and management, China Match Co set new standards and tackled technical problems like finding ways to stop matches being affected by moisture. In the second half year of the initial merger, the company reported earnings of 110,000 yinyuan, a real boost to an industry that had been losing money for years.

The September 18 Incident of 1931, which preceded Japan's invasion of Northeast China, sparked a nationwide boycott of foreign goods. Over the following years, China Match Co's Meili brand matches overtook Sweden's Phoenix brand in sales for the first time, a milestone for China's match industry.

Joint ventures

Liu was not just interested in matches. The St. John's University dropout was a business genius and invested in coal and cement but his forte was in creating joint ventures and competing against foreign companies.

In 1923 Liu founded the Shanghai Cement Company despite fierce market competition. He found himself in competition with two of the major cement companies of the time - the Chinese-owned Qixin Cement Company in Tangshan and the Japanese-owned Dragon brand cement business.

Liu went to Tianjin to talk with Qixin, suggesting they form a partnership and fight the Japanese company. Qixin agreed.

Another company, the China Cement Company, based in Nanjing, joined the joint venture in 1928 after Liu had talked with its executives, and soon the conglomerate accounted for 85 percent of China's cement production, successfully beating out Japanese companies.

During the 1930s, Liu Hongsheng was a true tycoon. As well as coal mines, match and cement factories, he founded the China Pier Company and owned three piers and more than 10 warehouses. He had opened porcelain and wool processing factories and established banks and insurance companies. At the peak of his career he was worth more than 20 million yinyuan.

In August 1937, the Battle of Shanghai began. Shanghai became a major battlefield in South China. The Japanese took over most of Liu's companies and properties, meaning he lost at least 10 million yinyuan in assets. Liu made a very bold move. To boost the weakened economy in Southwest China, he decided to move his factories to Guizhou, Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. He got his sons to remove more than 500 tons of machinery and raw materials from their Shanghai factories and transport them to the inland cities to reopen there. With little personal cash remaining, his interest in these new companies was diminished.

After the war Liu returned to Shanghai and re-established his companies here. In 1956, Liu's companies were nationalized and that year he passed away.