Lingering legacy

By Lu Qianwen Source:Global Times Published: 2013-4-21 17:28:01

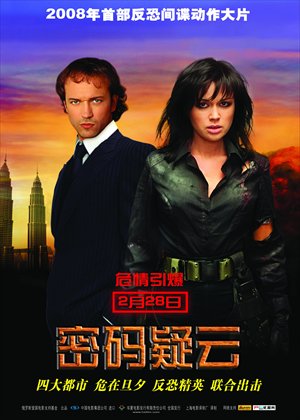

A movie poster for Russian film The Apocalypse Code

A scene from Hooked on the Game 2 Photos: CFP

Between the 1950s and 1980s when the USSR was a major world power, its films were as influential, famous and profitable as its vodka. And to Chinese audiences at the time, their stories seemed more appealing due to the two countries' similar political systems and ideologies.

Bygone memories

As China's big brother then, the Soviet Union fully exerted its influence in the film industry - from production to the values displayed. "Some Soviet directors had a deep influence on Chinese directors, mainly in how to show the films' artistic value and how to use the language of film," said Zhang Xiaodong, a film critic with expertise in Russian and films of the USSR.

Some of the most famous Chinese directors have also been influenced. Zhang Yimou once said Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-86, representative works include Andrei Rublev, Ivan's Childhood and Solaris) is one of the three directors he admires most.

"Tarkovsky's book Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema (1989), in which the author talks about his thoughts and inspirations on making films, has become a must-read book for many directors and films critics in China," said Zhang Xiaodong.

And for audiences, the influence of Soviet films was much wider in China. From Chapaev (1934), The Dawns Here Are Quiet (1972), Office Romance (1977), to Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1980, winner of Best Foreign Language Film at the 1981 Oscars), every one of them can refresh memories of the elder Chinese generations.

"Besides their influence on Chinese film production, Soviet films' emphasis on realism and romanticism has also affected the aesthetic value of our audiences and the production in other cultural and artistic aspects," said Huo Jianqi, a Chinese film director best known for his work Postmen in the Mountains in 1999.

With a strong hint of narrative story-telling, Soviet films overall were neither too commercial, nor too artistic to be understood. "They actually have very distinct styles, presenting people's spirit and high sense of responsibility then," said Zhang, "and I think this is an important reason why they resonated so much with Chinese audiences in that period."

Declining clout

With the breakup of this superpower in 1991, Russia gradually lagged behind in film production due to a lack of financial support and chaotic industry guidelines. (In the time of the Soviet Union, the film industry was state-owned, and this model was employed by China's film industry.)

Meanwhile in China, with the opening-up of many industrial sectors progressively deepening and Chinese audiences gaining more access to Western films especially Hollywood blockbusters, Russian films began to lose their foothold in China.

According to the statistics from Russian business magazine ChinaPRO between 2010 and 2011, the most profitable Russian film in China was We Are from the Future, with a box office of $3 million. When it premiered in Russia in 2008, it earned $8.5 million.

The box office for the next profitable Russian films like Hooked on the Game 2, The Apocalypse Code and The Rock Climber were all no more than $2.5 million, a large gap compared to earnings of Hollywood hits 2012 ($67.3 million) and Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen ($33.7 million), which premiered in China in 2009 and 2011 respectively.

However, despite the diminishing influence in China, Russian films have still gained a certain reputation in the world since the 1990s, not for its big-budget commercial films (an area that still lags behind the Hollywood standard), but for its artistic ones instead.

"Films like Burnt by the Sun (1994), The Barber of Siberia (1998) and 12 (2007), all by the country's veteran director Nikita Mikhalkov were still very popular in the world," said Zhang. Among them, Burnt by the Sun won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1995.

Russian notoriety is not limited to those veteran directors: Works by the country's younger directors' have also been attracting attention in the world. The Return (2003) by Andrei Zvyagintsev won the Golden Lion for best film at the 16th Venice Film Festival in 2003. And Zvyagintsev's two other films The Banishment (2007) and Elena (2011) were also regarded as representative works of Russian artistic films.

"It's not that Chinese people have lost interest in Russian films, but there is a limited introduction of the real valuable ones," said Zhang.

Co-productions underway

Not only are the number of Russian films in China limited due to the latter's quota on foreign films, but those that are introduced are often not the ones that have earned high recognition within the country or around the world.

"Maybe out of concern for the box office, domestic theaters mostly introduce those commercial Russian films. There should be more of [the country's] artistic films introduced to Chinese audiences. I think those will resonate with us like they did in the last century, since both countries have experienced so many tremendous social changes in recent decades," said Zhang.

Now to make more Russian films accessible to Chinese audiences, a two-pronged strategy is underway: First, Chinese theaters are increasing their efforts to scout out and introduce more high-quality Russian films to the country. Second, in 2011 China and Russia established a fund mainly for the co-production of films to circumvent the limit of China's quota on foreign films.

Under this fund, a group of films have been in production. These include Aerocade, which tells the story of Chinese and Soviet soldiers participating the Korean War in 1950; Beijing Duck, a story of several Russian people's experiences in China during the 1990s; and Russian fairy tale The Scarl Flower. They are expected to be presented in Chinese theaters in the upcoming years.

Posted in: Film