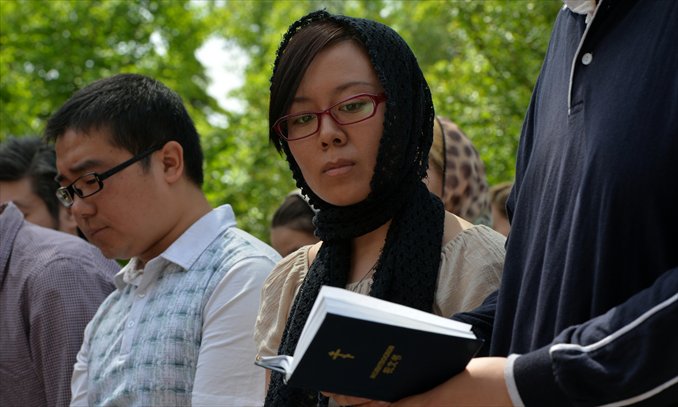

Orthodox Christians in China seeking official recognition

With a very small number of followers, practically no clergymen, and without official recognition, the Orthodox Church's situation in China is a precarious one. Researchers predict that the religion, imported from Russia, could disappear altogether in China within 15 years.

With Patriarch Kirill concluding his first official visit to China as head of the Church, Chinese Orthodox Christians are hoping that the religion will see something of a revival in China.

Sun Ming, who works as the guardian of an Orthodox church in the city of Erguna, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is one of them. His church, which can hold about 150 people, is one of the only four Orthodox churches in China that are approved for religious activities.

At 8:30 am on Sunday, Sun leads the service by reading a passage of scripture in Church Slavonic and then plays an audio tape of a Sunday service recorded in a Russian church. About a dozen people show up, most of whom are advanced in years.

Despite having studied in a Russian orthodox seminary for five years, Sun is not ordained and therefore cannot hold the service. In the entire mainland, there are only two Orthodox priests qualified to do so.

About 2,000 people of Russian ethnicity live in Erguna. Sun's grandmothers on both sides are Russian. His parents are also Orthodox Christians, but he didn't learn much about the religion when growing up.

There were celebrations during important occasions such as Easter or Christmas, but they were more like festivals rather than religious activities, he recalled.

Sun grew interested in his religion when he visited his relatives in Russia in 1997, where he went to church, and at 25 was christened.

There were previously 18 Orthodox churches and one house of prayer in Erguna before the 1960s, when Sun's grandparents could still go to church and attend religious activities. But the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) led to the destruction of most churches and the oppression of religion, leaving little opportunity for Sun's parents' generation to engage in religious activities.

Sun, 39, said that nowadays many traditions and rituals are observed only as part of the ethnic culture, while their religious significance is often neglected. He estimates that only a few hundred people in the Erguna area are Orthodox Christians.

Sun has been looking after the church for over a decade. In 1992, the local government and local people put together some money to build this church. But it was only in 2009 that the church was finally put to use. For a long time, there were no religious items or clergymen in the church.

The iconostasis, a wall of icons and religious paintings to the east of the church, was donated by Russia in 2003. But Chinese customs authorities denied it entry for five years because the religion isn't recognized in China.

Official recognition

China officially recognizes five religions, Buddhism, Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam and Taoism. These religions all have officially registered and approved churches or associations and are supervised by the religious authorities.

But the Orthodox churches remain open to followers. Besides this church in Erguna, there are two in Urumqi and Ili in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and Pokrovsky Cathedral in Harbin, which Patriarch Kirill visited on Tuesday.

Without legitimate status, it's difficult to maintain regular religious activities or set up churches.

There are about 400 Orthodox Christians in Beijing. Although the church inside the Russian embassy is open to everyone, regulations prevent Chinese people from going in, said Liu Yuxin, an Orthodox Christian in Beijing.

Without a place to hold religious activities, they've applied to build a church on their own, but the process has been stalled.

Orthodox Christianity has existed in China since 1685. Between then and 1924, Russia sent 18 Orthodox missions to China.

In 1955, the Orthodox Church in China became independent from the Russian Church. At its peak in the 1920s, there were over 300,000 followers, most of whom were Russian people or clergymen who came to China during the October Revolution, or children of Chinese and Russians.

According to estimates by the Russian Orthodox Church, there are about 15,000 Orthodox Christians in China today. But Chinese scholars believe there are probably only a few thousand, most of whom live in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang.

Shi Hengtan and Tang Xiaofeng, two researchers from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, studied the situation facing Orthodox believers in Harbin and Erguna in 2010.

They found that only a handful of Orthodox churches are kept in Harbin and only one is now used for religious activities.

No more than 30 to 40 people regularly attend Sunday services at the cathedral in Harbin, some of whom are Russian tourists or expats. Most of the followers are retirees.

Sun said that it's not only in China, but in Russia too, that the church is having difficulty attracting young people.

Staff shortages

One of the major problems facing Orthodox Christianity in China is a lack of clergymen. The last bishop in China passed away around the time of the Cultural Revolution. At present, there is one priest and one deacon, both in their 80s, in Shanghai.

Without a bishop, there is no way that the Orthodox in China could ordain any new priests by itself. But laws prohibit foreigners from ordaining members of the clergy in the country. Without priests, followers cannot get christened. Some people have gone to Hong Kong to get christened.

Because there are no priests to hold services, most followers come to church and pray on their own. In April 2010, the authorities invited a priest from Russia to preside over the Easter ceremony in Harbin. However, such occasions are rare.

The church in Erguna is only open on Sunday and for important religious occasions. Sun and one other person maintain the church, which has a limited source of income and just about manages to stay operational. The other churches are in a similar situation.

Shi and Tang estimated that if left alone without any support, the Orthodox Church may disappear in Harbin and Erguna in 10 to 15 years.

In 2001, Sun went to study at an Orthodox seminary in Moscow for five years and later interned in the city of Chita for a year. Over the years, about a dozen people have gone to study in Russian seminaries.

Even though Sun is properly qualified, he isn't ordained and therefore cannot hold any services, such as communion or hear confessions.

The authorities have also sent two students to study in Orthodox theological seminaries in Russia.

Lack of influence

Because the number of followers is so small, they have very little influence on the authorities, who would probably rather leave it alone, observed Shi, a researcher at the Institute of Religious Studies, CASS.

"The authorities probably don't want to make more trouble for themselves," he said.

Even with the five officially recognized religions, there are frictions, for instance, between the government-approved churches and other groups.

But experts say that the authorities need not worry too much because the Orthodox churches largely have not posed any threats to the state throughout history.

"Politically speaking, the Orthodox Church is a rather mild religion, and has not shown any desires to fight for power in the secular world," said Li Xing, a professor of international relations at Beijing Normal University who specializes in Russian studies.

History shows that the Orthodox Church has often been entwined with secular power. The relationship between the Orthodox Church and the Russian state has traditionally been close, as the church was strongly nationalistic.

In Russia today, the Orthodox Church represents about 80 percent of the population. "But its influence remains at the spiritual level," said Li.

Also unlike Catholicism, which recognizes the Pope as the leader of the Catholic churches all over the world, Orthodox Churches in different countries mostly remain independent from each other.

When Patriarch Kirill visited Beijing earlier this week, he was received by President Xi Jinping and celebrated a liturgy in Beijing.

For Chinese Orthodox Christians, some of whom were able to attend the ceremony and meet the Patriarch, the visit is a sign of hope. "I think it means that the Chinese authorities are gradually starting to recognize our existence," said Liu. "We hope the visit can help revive Orthodox Christianity in China."

During his visit, Patriarch Kirill expressed the wish that "the parishes of the Chinese Orthodox Church be granted registration, and at some moment there will be a Chinese bishop, so that the Chinese Orthodox Church can have a full life, can herself ordain her priests, organize places for worship and preach the gospel," according to the official website of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Media have mainly focused on the diplomatic issues when reporting on Kirill's visit.

In 2006, Kirill accompanied Putin during a visit to China as chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate department for external church relations. That was the first time China officially received a high-level Russian Orthodox clergyman.

Over the years, the Russian Orthodox Church has expressed a wish for China to officially recognize the religion and let it grow. Many followers are hoping that the Chinese authorities can make an exception in this case and let the Russian Church ordain a Chinese bishop so that the church can grow in China on its own.

But Sun understands that it all depends on the government's approach, saying that "It's more important to maintain the followers; otherwise, what use are members of the clergy if we no longer have any followers?"