HOME >> METRO SHANGHAI

Guns, ships and science

By Zhang Yu Source:Global Times Published: 2013-8-22 18:08:01

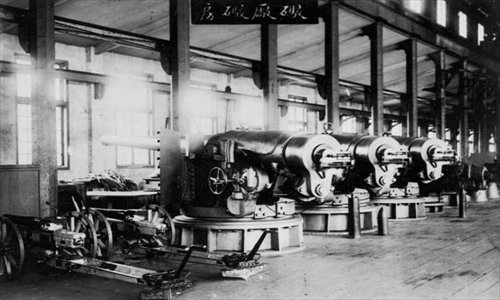

The cannon factory of the Kiangnan Arsenal

Today the cranes and machinery that line the Huangpu River are a signpost to the Shanghai shipbuilding industry and home to some of the country's largest shipbuilding companies. Modern shipbuilding began here 150 years ago as the country strengthened its military capabilities.For this China established the Nanking Arsenal, the Fuzhou Navy Yard, the Tianjin Arsenal and the Kiangnan Arsenal in Shanghai, a part of China's Self-Strengthening Movement, which was developed primarily by Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang.

In 1864, Li convinced the Qing government that a first-class arsenal was needed in the lower Yangtze River valley. Li himself went to Shanghai to find foreigners to teach the manufacture and use of arms - "to make the foreigners' special skills China's special skills."

Formally established in 1865, the Kiangnan Arsenal was the most impressive modern arms factory in China. In the period reigned by Emperor Tongzhi, it was peerless in East Asia and one of the greatest arsenals in the world, and, during the first few years of its establishment, China seemed to be coming abreast of the West.

The arsenal began life as Thomas Hunt and Company, an American iron firm in Hongkou district, which Li Hongzhang ordered Shanghai's customs official Ding Richang to purchase. It gathered some of the best equipment that could be found for the time, including machinery and raw materials brought in by Thomas Hunt.

It also merged two Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) cannon factories in Shanghai. Rong Hong (Yung Wing), the first Chinese student to graduate from a US university, bought back more than 100 manufacturing machines in New York and these too were sent to the Kiangnan Arsenal. It was officially titled the General Bureau of Machine Manufacture of Jiangnan.

Foreigners impressed

Foreigners who inspected the arsenal reported that they were impressed by the quality of production and products - and foreigners in those days were not generally enthusiastic about Chinese accomplishments. In 1866, the arsenal was reported as having enormous magazines, vast numbers of rifles and guns - an arsenal which "for extent may vie with those in the most powerful nations of Europe."

In 1867, only two years after the founding of the arsenal, the North China Herald stated, "It is now in such an efficient condition that all the tools and machinery needed are manufactured in the shop."

The arsenal's original purpose was to build warships to defend China from seagoing invaders. Foreign engineers were hired to work in the arsenal and in August 1868, the first ship, the Tianji ("Peaceful and Propitious") was completed. The 600-ton wooden steam-driven warship carried eight cannons and could travel at 21 kilometers an hour.

The arsenal carried out a number of other projects including prospecting for coal, refining iron, making guns and ammunition and training ships' officers. Most of the armaments the arsenal produced went to the armies of the northern warlords.

Workers were trained as machinists and boilermakers, which gave them, as skilled workers, wages four to eight times more than the average wage for ordinary workers and laborers. They were the first engineering workers and machinists in China.

In 1867, as business boomed, the original site proved too small and costly and the arsenal moved to the Gaochang Temple in southern Shanghai (on today's Zhizaoju Road in Huangpu district), where it grew into a large 43,000-square meter complex that included 13 factories manufacturing machinery, woodwork, guns, ammunition and gunpowder. This was where China's first machined tools, steel, smokeless gunpowder and cannons were manufactured.

By 1891, the complex spread over 246,000 square meters and the number of factory workers rose from the 200 when it was originally set up to nearly 3,000. Along with 600 management staff and supervisors, they together worked there alongside 662 lathes and presses and 361 steam engines.

Catching up

Although the Kiangnan Arsenal set many records in China, this was largely because the late Qing Dynasty had been backward in embracing technology and science. It was more about Li Hongzhang's desire to catch up with the West than making breakthroughs in its own.

As the arsenal relied heavily on foreign machinery and raw materials and employed a huge number of workers on high wages, running costs were enormous. The cost to make a ship there was twice the price of a ship imported directly from Britain and the ship was slower and less efficient.

Each rifle manufactured there cost 17.4 taels of silver, while foreign-made arms cost just 10 taels. At one stage Li Hongzhang's own troops reportedly refused to use Kiangnan rifles because they were inefficient.

Seventy years after the arsenal had been established and began production, however, it became obvious it would never realize the dream of its founders to match the West in armaments and production.

Alongside its manufacturing arm, the arsenal had a highly-regarded translation office and by 1871 it was publishing translations of scientific, engineering, military and other papers. The office was the creation of two Chinese scientists, Hua Hengfang and Xu Shou, who were inspired by Jesuit translations and the "Medical Missionary" Benjamin Hobson. They came to work in the arsenal in 1867, and soon persuaded the director that the arsenal needed better information and they should establish a translation office for the complex.

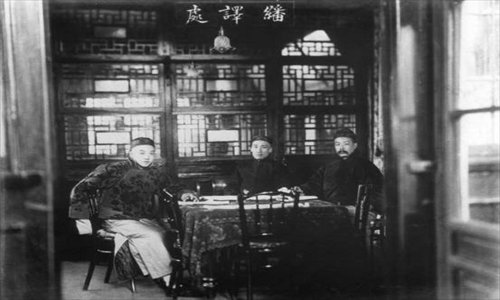

The translation office opened in 1868, with Hua, Xu and Xu Jianyin, Xu Shou's son, as the first Chinese staff members along with the English-speaking John Fryer, Alexander Wylie, John MacGowan and Carl Kryer. A total of 59 scientists and scholars were involved in the office which at first produced papers and books on armaments and ammunition, some of which were used as textbooks at the arsenal's school.

Chinese and foreign scholars worked together in the office - the foreigners translating and explaining texts as the Chinese transcribed the words into Chinese characters, creating new forms when there were no existing words or symbols. The office had a printing house attached to it and by 1909 it had published over 180 books, making it the largest and most influential translation publisher in modern China.

Since his earlier experience had been building steamships, it was natural that Xu Shou's first translation, published in 1871, was The Origin of the Steam Engine. The translators were free to select titles from the hundreds of books Fryer had delivered from England.

Notable titles that the office introduced to China included The Outlines of Astronomy by British astronomer John Frederick Herschel and Elements of Geology by Charles Lyell. The characters for "technology," "molecule," "inherit," and "neuron," which had never before existed in the Chinese language, were coined by translation scholars here.

The translation scholars also showed an interest in the social sciences. Among the 160 volumes published between 1868 and 1907, about 30 books were about liberal arts and social sciences, politics, law and military strategy.

One important publication was Compilations of Recent Developments in the West, an annual translation of excerpts from British newspapers like The Times, collating major events in the West. The noted Chinese scholar Liang Qichao said these were a "must read" for people interested in current affairs.

These books influenced the thinking of many modern Chinese scholars like Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao and Li Hongzhang. In some aspects, the value of Kiangnan Arsenal's translation office was greater than that of the arsenal itself, as it brought fresh new ideas from the West to China and influenced China's technical and social development.

Xu Jianyin, Hua Hengfang and Xu Shou (from left to right) were the earliest Chinese staff of the translation office of the Kiangnan Arsenal.

A major playerAfter the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Kiangnan Arsenal was renamed the Jiangnan Shipyard, and became a major part of China's shipping industry, building the first wholly Chinese-designed vessel, the first submarine and the first corvette.

In 1996, the company was corporatized as the Jiangnan Shipyard Group. In 2008, on its 143rd anniversary, the shipyard moved to Changxing Island in northeastern Shanghai. The shipyard's website states that it aims to become China's number one military shipbuilder by 2015.

Its military connections have often shrouded the company in mystery. In 2011, there was a flurry of rumors that the Jiangnan Shipyard would build China's first aircraft carrier. Visitors curious about the past can look over the history of the shipyard at the Shanghai Jiangnan Shipbuilding Museum, on Luban Road in Huangpu district.

Posted in: Metro Shanghai, Meeting up with old Shanghai