Dressed to thrill

The origin of the popular adage "there is nothing the Cantonese will refuse to eat and nothing the Shanghainese will refuse to wear" might well have been lost over the decades but the fact remains that Shanghai is the country's fashion capital, a position that can be traced back to the 1920s when it became a modern metropolis. Shanghai Glamour, a current exhibition at New York's Museum of Chinese in America, documents the city's fashion scene through early to mid 1900s, and notes that Shanghai people and their fashionable dress "epitomized the seduction and mystery of this legendary city."

During the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), women in Shanghai wore skirts or trousers under a long tunic (ao) while scholars and men of distinction wore full-length Manchu robes (changshan). After the Republic of China was founded in 1912, women were allowed into the universities and thus entered professions previously reserved for men. This, according to Hazel Clark, the author of The Cheongsam, called for a more egalitarian form of dress.

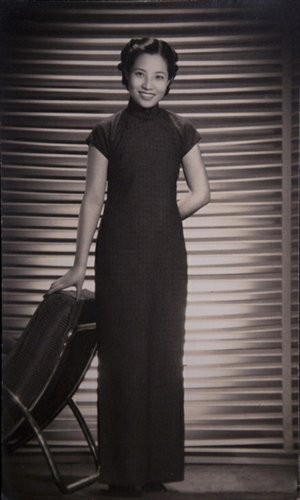

In 1920, China's earliest pictorial journal Jiefang Huabao and a major newspaper Shi Bao reported that the cheongsam (also known as qipao) had become hugely popular for women in Shanghai. An evolution from the classless and androgynous changshan worn by men, the cheongsam freed them from layers of restricting garments. Eileen Chang, in A Chronicle of Changing Clothes, said "in 1921, women put on long cheongsams."

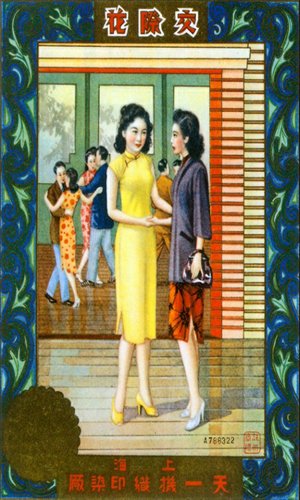

The city's trendsetting socialites contributed to the popularity of the cheongsam. Tang Ying, one of Shanghai's best-known socialites, was more than a cheongsam enthusiast and collector. In 1927, she opened her own dressmaking company specializing in cheongsams. The company, Yunshang, was established in a three-story house near Jing'an Temple and Tang won celebrity endorsement from the legendary artist and socialite Lu Xiaoman, and hired designers who had studied in France and Japan. This Shanghai cheongsam brand was soon sought after not just in Shanghai, but by women in Nanjing, Suzhou, Beijing and Tianjin.

Decidedly feminine

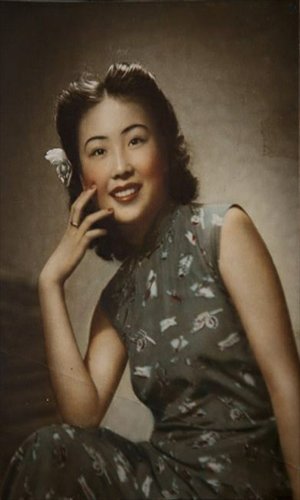

While the cheongsam was adopted in the early 1920s as a symbol of equality, it went on to become a decidedly feminine garment. The popularity of Hollywood cinema in the late 1920s kept Shanghai women up to date with international fashion and generated preferences for more closely fitted, body-hugging cheongsams. The introduction of bust darts, waist darts, and shoulder slits in the early 1930s made the cheongsam even more flattering.

The fashionable length of the garment, just like Western skirts, soared and dropped. The hemline for cheongsams rose to just below the knee by the end of the 1920s, then between 1932 and 1938 it dropped to the floor, according to The History of Chinese Qipao Culture by Liu Yu. After 1939, it rose to the lower mid-calf levels.

Variations were also regularly introduced to the collars and sleeves: turndown collars, V-necks, ruffled collars and sleeves and slit sleeves gained popularity. Not only were these Western designs embraced but the materials themselves became more Western. With Shanghai's textile industry in full bloom cheongsams could be created in satin, silk, wool and velour. Most people on modest budgets however chose cheongsams made from rayon.

Floral patterns were consistently popular with flowers decorating the bodies of the dresses and the cuffs and hems. Geometric designs, a signature theme of art deco designs, were also common.

While some designs were more daring, most were subtle and showcased international sophistication. Wearers could be perfect examples of mix-and-match fashions with Western fur-trimmed coats or down jackets worn over cheongsams and high-heeled shoes or boots.

In the 1940s, cheongsams continued to be slim-fitting. While the side-slits were not as high as in the 1930s and revealed less leg, sleeveless cheongsams took the stage in summer, baring arms.

After the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, the distinctly feminine cheongsam gave way to the "'people's suit" the drab plain jacket and trousers. In the early 1950s, the cheongsam almost disappeared from everyday life. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), the cheongsam was classified as "decadent" and many cheongsam collections in the city were destroyed and burned.

In the movies

Although the internationally acclaimed movies The World of Suzie Wong (1960) and In the Mood for Love (2000) were famous for promoting the charm of cheongsams, both stories were not set in Shanghai but Hong Kong. A better cinematic record of Shanghai women and the cheongsam might be Everlasting Regret (2005), in which the heroine (played by Sammi Cheng) a beauty contestant who lives her life through some of Shanghai's turbulent years, wears a variety of cheongsams from a gray striped cotton version to one that is a dazzling red and fully embroidered.

As well as the cheongsam the other essential for a stylish Shanghai woman's wardrobe was a pair of stockings. Stockings had first arrived in the city in the 1850s. Yu Qianchu, a Cantonese businessman returned from a trip to Europe along with a Western stocking maker and opened the Guangshengxiang store on Guangdong Road in 1857. He began selling imported stockings from English manufacturers based in Hong Kong but soon began to design and make his own products.

Later in the 1920s, silk stockings became the local fashion, as they served as perfect accessories to the high slit or shorter cheongsams. In the 1930s, the spotlight was on high quality silk stockings, which the locals called "glass stockings." Introduced by the US company DuPont, the stockings were described as a "second skin" being transparent and comfortable with a gloss that made a woman's legs appear slimmer. Film stars and socialites including the movie queen Ruan Lingyu were big fans.

Underneath the cheongsam there was a revolution as well. The British newspaper The Independent said that in 1907 the American Vogue magazine coined the word brassiere to refer to the undergarment that supports and lifts a woman's bosom. World War I (1914-1918) saw more and more Western women abandoning corsets and turning to bras.

Domestic brassieres were accessible in the early 1930s with a Russian businessman opening China's first bra and lingerie store, called Gujin, the magazine Vantage Shanghai reported. It was located at 859 Xiafei Road (now 865 Huaihai Road Middle), and provided personal service for the customers who reportedly welcomed the simplicity of the new garments and enjoyed more confidence wearing them.

On the top

In the 1920s, Shanghai women kept their hairstyles simple often by tying their hair in a knot, sometimes decorated with a ribbon or a flower. Another popular style was the ear-length bob with a straight fringe, a look popular with girl students and intellectuals.

When permanent waves arrived in Shanghai in 1920, foreign hair salons began to provide the service in the concessions, but perms were only enjoyed by the well-off as the price was a hefty 20 silver dollars - around that time, according to shtong.gov.cn, most factory workers earned 9 silver dollars a month while shop assistants made between 16 and 30 silver dollars monthly. By the 1930s, reasonably priced Chinese hair salons were offering perms to their customers and the technique became commonplace.

With perms women could have curls in their hair and shoulder length curly hair became the fashion of the time. By the 1940s hair wax or pomade (the precursors to gel) had arrived to enhance the stylists' visions and kept unruly bangs in place.

Makeup in the 1920s highlighted fair complexions, arched eyebrows, and rosy lips. In the 1930s, the traditional appreciation of slanted eyes gave way to an appreciation of large eyes, generating a fondness for darker eye shadows. Bright lip colors were also in vogue.

Imported cosmetics like those from Max Factor from the US were coveted during the 1930s. When 17-year-old Eileen Chang earned her first paycheck of 5 silver dollars for a newspaper in 1937, she bought a Max Factor lipstick. Other popular imported brands included Bourjois from France, 4711 from Germany, and the more expensive Elizabeth Arden from the US.

Well suited

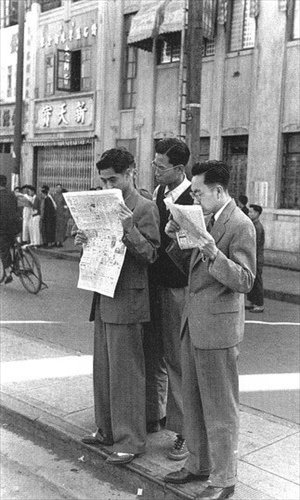

Shanghai men, who were not noted for being well-dressed and suave, enjoyed a style evolution too. Tailored suit shops emerged in Shanghai around the 1850s - most of the tailors then were British or Jewish. They passed their craft on to apprentices who came to the city from Ningbo and Fenghua in Zhejiang Province, and these new Chinese tailors became famed for their skill. In 1896, the first homegrown Chinese tailored suit shop, Hechang, opened on Sichuan Road North. More homegrown tailor's shops run by Zhejiang tailors like Wangxingchang and Rongchangxiang soon followed step.

Chinese suits were made along the lines of the traditional European suits - with jacket, vest and trousers. Apart from expats, in the early days in the city only middle class office workers employed by foreign firms and students who had been educated abroad wore suits. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the suit became an unofficial compulsory uniform for office workers in Shanghai and even the lowest clerk would have two or three suits to maintain the image.

While the suit remained a suit, unlike the fashion variations in style for cheongsams, the shirts worn with the three pieces changed frequently. Standing collars were popular early on until they gave way to round and later peak collars. Shirts couldn't be worn without ties which came in a variety of colors and styles. For a while there was a custom where a young woman would cut a piece of her cheongsam from the hem and send it to the young man she fancied. He, in turn, would wear this as a tie to publicly display his affection.

While most suits for city office workers were made by local tailors, the wealthy and the famous had their suits made in British, French, and Italian shops. Mu Xin, a noted Zhejiang painter and writer who was studying art in Shanghai in the 1940s, wrote in his article A Tribute to Shanghai that the city's middle-aged and older gentlemen chose British tailors while their rich sons went to French shops and show business stars frequented Italian shops.

The Sun Yat-sen suit, named after the Republic of China's founding father (although it was also dubbed the Mao suit in the West), was added to men's wardrobes from the early 1920s. This showed influences of military and school uniforms, along with Western suits in a design fashioned by Sun's ideas and preferences.

While there are several stories of the origin of the suit it remains a mystery whether Shanghai was the actual birthplace. But the city was one of the earliest cities in which tailor-made clothes were offered to the public. Shanghai's Zhejiang tailors made and sold both Western-style and Sun Yat-sen suits. Rongchangxiang, one of the major tailor shops, was famous for reportedly being visited by Sun Yat-sen himself, and claimed that "The Sun Yat-sen suit is a must-have for the people." Sun Yat-sen suits were taken up enthusiastically by the city's pro-revolution students - along with civil servants, who were obliged to wear them.