Children of the Revolution

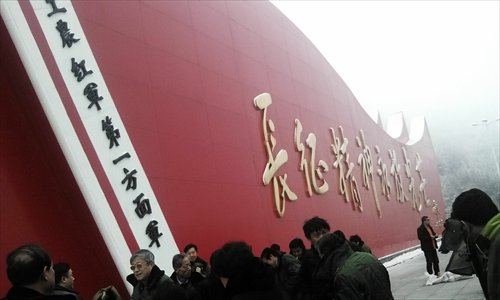

Sons and daughters of former revolution leaders visit Liupan Mountain Red Army Museum late last month. Photo: Liang Chen/GT

In late October, some 130 children of former top leaders in the Communist Party of China were invited to Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, to launch an exhibition of Chairman Mao's calligraphy and poetry. During a two-day tour, they were invited to visit red revolutionary bases and museums in Ningxia.

"It is a baptism. As the children of revolutionaries, revisiting these places where our fathers fought can refresh us and remind us of the hard-earned victory," Chen Weihua, daughter of Chen Yun, founder of China's economic construction, told the Global Times.

"We shoulder the responsibility for inheriting the spirit of the red revolution. This spirit cannot be abandoned."

The children of former prominent revolutionary officials refer to themselves as hongerdai - the second red generation - clearly distinguishing themselves from guanerdai, the sons and daughters of current officials.

"You shouldn't mix up the concept. Our parents fought battles and established the country. We have been taught to inherit the red spirit of the Red Army, work hard and maintain plain lives since we were children. We're totally different from the second generation of current officials who are likely to abuse power to seize personal gains," Cao Yunshan, grandson of Mao Zemin, the younger brother of Mao Zedong, told the Global Times.

For most "princelings" - a term given to the children of past senior Party leaders - one of their main tasks is to inherit the red spirit of the revolutionaries.

One way of promoting this red spirit is by attending commemorative events for the birth anniversary of Chairman Mao and other prominent leaders.

This year marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Chairman Mao, an event for which Chen and her comrades have always been honored guests.

Cao has made it his task to collect historical materials to restore the image of Mao Zemin, a brother of Mao Zedong. He has visited archives in Russia several times to collect rarely seen historical files and published two books about Mao Zemin.

"So many martyrs sacrificed themselves for the founding of the country. However, people have little knowledge about them. As descendants, we have the duty to restore history and pass on the spirit of the Red Army," Cao said.

Yang Shaoming (second from left) and his hongerdai friends. Photo: Liang Chen/GT

Shunning politics

Yang Shaoming, son of Yang Shangkun, China's president from 1988 to 1993, has chosen a life that could not be more different than his father's.

Shunning politics, Yang has decided to work as a photographer and a philanthropist.

Since 1979, he has been working for the Xinhua News Agency. He spent 12 years photographing late leader Deng Xiaoping, the chief architect of China's reform and opening-up strategy.

Now, Yang has shifted his focus to public welfare, serving as vice president of the Soong Ching Ling Foundation, an NGO dedicated to promoting the healthcare and cultural education of women and children. Recently, he successfully raised millions of yuan so that children in West China could receive free education.

Yang's case is not an isolated one. Many of China's hongerdai have decided to stay away from politics and use their abilities in a variety of areas ranging from business and writing to editing and teaching.

They seldom live in the media spotlight. Mostly in their 60s, they pay a great deal of attention to society, public welfare and political changes. However, most of them deliberately avoid publicly discussing sensitive topics, such as Chairman Mao's achievements and mistakes and their personal hopes for politics.

"Politics is complicated. Nowadays, if you want to climb up the political ladder, you have to go against your heart sometimes," Yang, who has negative opinions on the work style of many officials, told the Global Times.

"Simply put, you have to bribe people if you want to get promoted."

People like Yang may have made their choices for a variety of reasons, but for many, the trauma inflicted on them and their father's generation by the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) is the main cause.

The tumult that Yang witnessed when his family was targeted during the Cultural Revolution was what drove him to a life free from politics.

Even though over 30 years have passed, Yang could not hold back his tears when he recalled to the Global Times the trauma caused by the chaos, taking several long pauses to gather himself when talking about this tumultuous chapter in Chinese history.

In May 1966, when the campaign started, his father Yang Shangkun was denounced as a "counter-revolutionary element" and was put under house arrest for the next 12 years. His wife was beaten and humiliated.

Yang Shaoming, a history major in Peking University at that time, was implicated, verbally abused and physically beaten at struggle sessions. One person threw a spear at the back of Yang's head, causing him to fall into a prolonged coma. The long scar on the back of his head remains a shocking sight even today.

Yang said the torture was unforgettable. More than once, he thought about committing suicide.

Chen Xiaolu, son of marshal Chen Yi, visits an exhibition of the Red Army in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, October 19. Photo: Liang Chen/GT

Keeping the spirit

Despite the havoc that the Cultural Revolution wreaked on Yang and other children of senior officials, they remain nostalgic about Mao's time when he led the Red Army to found a country. "The Long March is unforgettable. Officials and people closely united together, held a strong belief and fought hard for it," Yang told the Global Times.

Chen Xiaolu, the youngest son of People's Liberation Army Marshal Chen Yi, a national hero, is a promoter of the red spirit.

When commenting on the impact of the Cultural Revolution and Mao's merits and faults, Chen said, "Mao's merits outweighed his shortcomings" - a consensus held among hongerdai.

However, Chen recognizes the Cultural Revolution as a mistake and apologized in a high-profile gesture in October to his teachers whom he persecuted when he was a "red guard."

Chen and other hongerdai tend not to blame the Cultural Revolution entirely on Mao, who, they say, was not in full control of the situation at that time.

Chen's father had been criticized and reprimanded during the chaos. After his father was rehabilitated in 1971, Chen Xiaolu was dispatched to serve in the army. However, he left in 1992 with the rank of colonel and went into business in Hainan.

"Why did I leave the army? I hated seeing their unjust behavior and acts," he said.

People like Chen have long been concerned about the growing public discontent with official corruption, he noted.

"Corruption is a life-and-death issue. The lowest organ of government, the village committee, has become corrupt," Chen said, adding that many village officials bribe their villagers to get power.

"Why have so many corrupt officials fallen from grace? They didn't stick to the spirit of Mao Zedong Thought, which is to serve the people."

Chen insisted that if officials stick to the "spirit of Jinggangshan," the revolutionary spirit of the CPC that promotes officials maintaining close ties with masses, Party unity and hard work, officials would not be corrupt.

Chen said most of the children of former senior Party officials are disappointed with the political situation, but not yet desperate. Critics say that vested interest groups nowadays have amassed huge wealth by using their connections to engage in business that is closely tied to the State.

One of the most famous cases is that of Bo Xilai, former Chongqing Party chief and also a "princeling," who was sentenced to life imprisonment for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power.

Making connections

Despite these efforts to remain apart from the political process, their distinctive family backgrounds have given them rich social resources and connections that are very tempting to officials, companies and agencies.

Contact with hongerdai has a very real political significance in China, where a culture of human relationships dominates society.

Undeniably, Chen Xiaolu and his "brothers and sisters" (a term that the children of senior Party revolutionaries use for each other) have always been welcomed by officials and companies.

In Ningxia, wherever they went, local officials would greet them warmly, prepare feasts and invite representatives to give speeches and write inscriptions as gifts to the local government.

"In the key moment for our county to build a well-off society in an all-round way, it is uplifting that the children of the Party's revolutionaries visit us," Zhang Xingbin, the Party Secretary of Tongxin county, where Chairman Mao once fought during the Long March, said in an address at a dinner reception hosted by the local government.

Ma Honghai, head of Tongxin county, told the Global Times that it is a great honor to work as an official where Chairman Mao once made base on his Long March.

"The 'red roots' of Tongxin county have also helped boost the local economy. Tongxin has developed rapidly under the care of the central government," Ma told the Global Times.

The central government has allocated tens of millions of yuan and preferential policies to support the county's economic development, Ma said. Tongxin was also the first county in Ningxia to provide tap water to all its villages, he noted.

"The attendance and inscriptions can bring in practical political and economic benefits for local officials. It will attract public attention and add weight to their activities if the descendants of Party leaders attend," a researcher on modern history from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences told the Global Times.

It is also a nice addition to their political résumé, Lei added.