HOME >> OP-ED

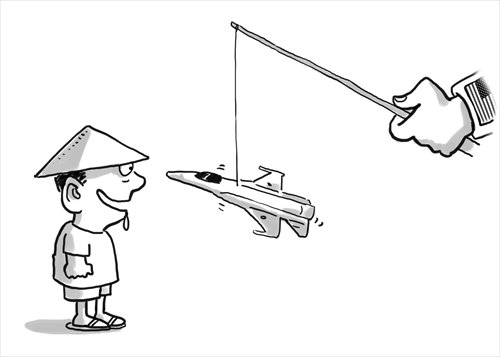

US arms sales make waves in S.China Sea

By Li Kaisheng Source:Global Times Published: 2014-10-9 22:53:01

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Sino-Vietnamese relations are at a low ebb following China's deployment of an oil rig in the Xisha Islands in May and the riots sparked by Vietnamese anti-China demonstrations. The massive backlash was unexpected for decision-makers in both countries, and since then the two sides have been working to mend the relationship.

While the grudges between the two are unlikely to be fixed by a single visit, bilateral relations are beginning to get back on track. This will be helpful for resolving disputes over the South China Sea peacefully and stabilizing the regional situation.

But then came the US decision to partially lift its ban on the sale of lethal weapons to Vietnam, announced on October 2. The announcement was not surprising, as Washington has been strengthening its military cooperation with Hanoi through frequent visits by senior army officials on both sides.

In August, Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, landed in Hanoi, the first visit by a chairman since 1971.

The US has maintained an arms embargo on Vietnam since the end of the Vietnam War. But it has chosen to ease the ban at a critical moment in relations between Beijing and Hanoi. It's fair to doubt the timing and motivation of the US policy shift.

The response of the Vietnamese sides to the US move is also worth noticing. Vietnam's senior officials applauded the easing of the ban, saying such a move shouldn't worry China.

Beijing certainly won't worry about any damage that the weapons sales may cause to China's substantial interests. What it is concerned is that the momentum toward improving Sino-Vietnamese relations and stabilizing the situation in the South China Sea may be reversed by the latest US move.

Mutual trust between Beijing and Hanoi remains fragile, and a Vietnam supported by US weapons may be more reluctant to negotiate a peaceful settlement to territorial disputes.

The weapons sales benefit the US, as it can easily push Vietnam to the front line of its strategy to contain China, stacking another chip in the great power game. Greater difficulty resolving disputes over the South China Sea and the rising possibility of conflict have put regional stability and peace in jeopardy.

Recently on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York, Vietnamese Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh said the Asia-Pacific region faces an unprecedented risk of military conflict over territorial disputes.

What he didn't mention is that dragging the US into the disputes also adds to the risk. With regard to disputes over the South China Sea, smaller countries such as Vietnam tend to put all the blame on China while ignoring their own wrongdoings. Such regrettable, emotional actions do nothing to help promote rational, peaceful resolutions to disputes in the South China Sea.

In fact, Vietnam will actually suffer from the easing of the ban. China and Vietnam are neighbors who share a border. Both are geographically distant from the US, and conflicts triggered by US arms sales will only hurt the two instead of the US.

Despite its arms sales, the US will definitely not send troops to help Vietnam in the event of a conflict. This isn't due to any weakness in American military power in the region, but rather because Washington does not have any interests in the region worth the risk of fighting China. The fundamental code of conduct for the US is its national interest, rather than the interests of East Asian countries or regional stability and peace.

It's natural for territorial disputes to occur between neighboring countries. What's critical is for the countries involved to calmly manage the differences, and resolve disputes through peaceful consultations.

Some argue that Beijing has become "assertive" on territorial issues in recent years, but a fact often ignored is that China has resolved its land territorial disputes with a dozen of neighbors through negotiations.

China has taken certain counter-measures in response to some countries' actions, including building islands and extracting oil, which have changed or are changing the status quo. The steps are compensatory in nature.

China will take further steps if these countries don't put a stop to their actions; but at the same time, it stands ready to negotiate at any time.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has initiated a dual-track approach, wherein relevant disputes are addressed by the countries directly concerned through peaceful, friendly consultations and negotiations, and through joint efforts by China and ASEAN countries to maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea. This is yet another sign of China's sincerity.

All relevant countries should take this opportunity to sit down and talk about how to maintain the stability of the overall situation in the South China Sea and to properly resolve disputes over sovereignty.

An insistence on a so-called "internationalized" solution that drags in an irrelevant country will only push solutions further out of reach. The victims of the resulting disturbances to regional stability and peace will be the countries of the region.

The author is an associate research fellow at the Institute of International Relations, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Posted in: Viewpoint