Changing times have traditional political cartoons on the wane in China

Political cartoons are having a hard time in China, a far cry from the "Golden Age" of the 1980s. Behind the decline lie weakening print media and a distaste for satire and confrontation deeply ingrained in Chinese traditional values. But some cartoonists believe that social media could help revive China's flagging political cartoon tradition.

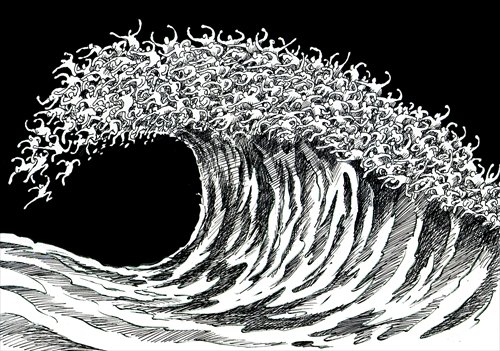

A cartoon named Fury Wave by Kuang Biao Photo: Courtesy of Kuang Biao

A baby sheep aims a hard kick at an ugly man, dressed like an ancient Chinese charlatan and holding a banner that says "Nine out of 10 people born in the year of the sheep have unlucky lives."

The cartoon, criticizing a superstition that is likely to cause a drop in newborn babies in the coming Year of the Sheep in China, was the front-page cartoon on the latest issue of Satire and Humor, a weekly Chinese newspaper that publishes political cartoons along with social and political commentary.

When the world was talking about the terrorist attack on French magazine Charlie Hebdo and lamenting the terrible price for free speech, Chinese cartoon publications seemed to be keeping a distance from the discussion. Many of them are quietly sinking into oblivion.

Once China's most popular cartoon newspaper, Satire and Humor, for example, is now hard to find at the country's newsstands, so it's no surprise that its circulation has shrunk over 90 percent, from 1.32 million copies during its peak in the 1980s to around 80,000 copies today, according to Xiao Chengsen, the publication's managing editor-in-chief. "We feel embarrassed when compared with our predecessors," Xiao, aged 50, told the Global Times.

The decline of China's only remaining cartoon newspaper is a reminder of the bitter situation facing China's political cartoons today, complicated by factors including the decline of print media, a distaste for satire and confrontation deeply ingrained in Chinese traditional values.

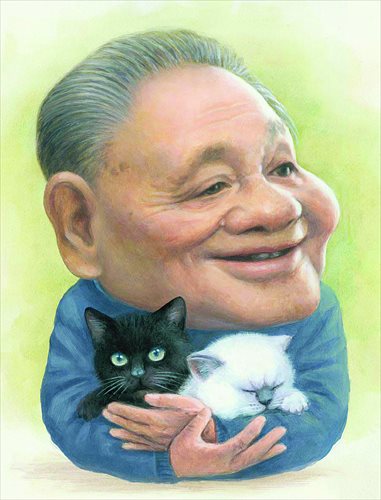

Caricature of Deng Xiaoping by Zhu Zizun with Deng holding one white cat and one black cat in his arms, a tribute to his famous remark: "It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it can catch mice," referring to China's choice of economic systems. Photo: Courtesy of Zhu Zizun

A glorious history

In January 1979, cartoonist Ying Tao founded Satire and Humor as a supplement of People's Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China (CPC), with the approval of Hu Yaobang, then head of the Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee. The Gang of Four, the political clique that was believed to be behind the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and other backward social phenomenon in the society, were its main targets.

The paper's birth marked the beginning of a golden age of China's political cartoons. The Cultural Revolution had just ended, and artists, both professional and amateur, threw off the ideological shackles of the movement and stepped into the new age with hopes for freer speech and more space for art.

In an interview with the Associated Press in 1986, Ying said the paper received over 100 cartoons a day from enthusiastic amateurs who wanted to have their satirical or humorous works published.

Hungry after 10 years of drab cultural and political life during the Cultural Revolution, readers vented their pent-up emotions through reading the paper's pungent and witty criticism of the Gang of Four and other current events. According to a memoir by Ying, in the 1980s, people would line up in front of the post offices on the morning of each publication day, waiting to buy the paper. At newsstands, copies were often sold out within hours. Circulation soared.

It was also a golden age for editorial cartoons in general. Apart from Satire and Humor, The World of Cartoons, a weekly newspaper, was launched in Shanghai in 1985 and Cartoon Monthly, the first cartoon magazine in China, was launched in Hebei Province in the same year.

Xiao recalled that in the 1980s, almost every local-level Party newspaper had a cartoon column. A worker at a factory in Shenyang, Liaoning Province at that time, Xiao started his painting career by sending his amateur works to local newspapers.

His first work was published in 1988 on Yingkou Daily, Party newspaper of Yingkou, a port city in Liaoning Province. "It depicted a Buddhist temple which was turned into a kasaya shop, criticizing the nationwide business fever at that time," Xiao said.

No appetite for satire

But all that is a distant memory. The past decade saw Shanghai's Cartoon World fold and Cartoon Monthly switch to print comic strips in a market-driven change. In the meantime, the number of cartoon columns in newspapers dwindled to almost nothing. Xiao estimates that only 20 newspapers in China still publish editorial cartoons on a regular basis today.

The critical nature of political cartoons is considered a major reason they are not welcomed by the Chinese officials.

"The essence of a political cartoon is satire. Politicians in China are used to praises and applause. It's natural that they have no appetite for thorny satire, especially in publications they view as their publicity tools," Gouben, a professional cartoonist who contributes to newspapers including Southern Weekend, Southern Metropolis Daily and The Beijing News, told the Global Times.

"Many local newspaper publishers do not understand the humor in a cartoon and think of them as liabilities that may offend officials," Xiao said.

Cartoonists have to also face stringent regulations by the media on their work. "For example, some newspapers had a requirement that officials involved in news scandals should not be caricatured. They can't even be painted as fatter than they really are," Gouben said.

Kuang Biao, former editor of the cartoon page at Southern Metropolis Daily in 2008, said he had to prepare two to three back-up works each week in case a cartoon had to be revised or pulled completely.

"In less than a year, authorities asked the cartoon page to shut down, and I was ordered not to launch a new one," Kuang told the Global Times. He left Southern Metropolis Daily in 2013 and now works as the art director at a newspaper in Hong Kong.

Chinese cartoonists have to adopt oblique techniques when they want to express their criticism. Allusions and metaphors abound. "Because of this, our works are sometimes more witty and classy than our Western counterparts, and are more thought-provoking," Kuang said.

Last year, active online cartoonist Wang Liming, known on China's social media Weibo as Pervert Hot Pepper, said he was forced to move to Japan after he was attacked by some newspapers for being a "traitor" and had all his social media accounts forcibly deleted. Wang, however, argues that his outspoken cartoons were the real reason why he was under attack.

"It's not difficult to see why he is so hated. His works are too straightforward - like poking a man's heart with a knife. Besides, his views are too subjective and sometimes radical," Kuang said.

In the meantime, Chinese authorities have allowed cartoon depictions of China's leadership to appear in the media for the first time since the 1980s, as part of a broader Party publicity push. Caricatures of former and current central government leaders such as Jiang Zemin and Xi Jinping, painted by artist Zhu Zizun, for example, were exhibited during a cartoon festival last year in Hangzhou, and cartoon drawings of Peng Liyuan, China's first lady, went viral online.

Finding new life online

While most people working in media in China are in their 20s or 30s, most of the cartoonists who are still active in the media are men in their 40s and 50s. "Without a certain amount of social and life experiences, it's hard for artists to draw powerful and trenchant political cartoons," Kuang said.

But a new generation of political cartoonists are already emerging on social media, with modern styles that cater to young people's tastes and faster drawing techniques that allow them to respond more quickly to current events. "I'm not worried about the future of China's political cartoons. Painters like Gouben, Dashixiong and others are not just active in newspaper but more importantly, on social media. They are taking over our role," Kuang said.

Cartoonists believe that social media will bring a revival to China's political cartoons. In fact, Weibo has already witnessed the births of creative new forms of news cartoons. One of them is "character news" created by Wang Zuozhongyou, who tells news stories by deconstructing Chinese characters and numbers, replacing radicals with paintings.

One of his famous works depicts the number 500 with the two 0's resembling a pair of handcuffs. The cartoon was an indirect reference to a 2013 ruling that bloggers can be sent to jail for online posts containing false information which are reposted more than 500 times.

Wang Zuozhongyou has kept his real name and identity a secret, revealing only that he works in the media. Zuozhongyou is Wang's pseudonym, which literally means "left middle right," expressing his view that his work has no political inclinations. "I choose to draw cartoons on news that are already widespread on the social media. Most of the time, I try to be objective and only describe the facts in my cartoons," he told the Global Times.

In reality, however, Wang's choice of subject, including the arrest of lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and the blocking of Gmail in China, reveals his liberal inclination.

Many of his works were censored on Weibo, and his public account on WeChat, Tencent's popular messaging app, where he sends latest works to subscribers, was shut down at the beginning of 2014. Even so, cartoonists are still optimistic about the future. "The space for art on the Internet is much bigger, and we now have more channels to publish our works," Xiao said. "In this [digital] age, as long as cartoonists have a free mind and an independent soul, they can find outlets to pour their energy into," said Kuang.

Newspaper headline: Out of toon