Unlike Western street art, vandalism in China serves a utilitarian purpose

Fapiao (fake invoices) ad written on a crosswalk Photo: Tom Carter/GT

In 1987, when I was just 14 years old, I ran with the biggest tagging crews in San Francisco. My accomplices and I ditched most of the ninth grade to ride around all day on Muni, the city's public transportation, scrawling graffiti on bus windows and the sides of the subway. At one point I - or rather, my alias - was Muni's most wanted, but I was never caught. Hopefully the statute of limitations has expired, as I've never publicly confessed my role in what probably cost the San Francisco municipal government "hella" thousands of dollars to clean up.

Sticker ads from factories making rolling shutters Photo: Tom Carter/GT

Now that I am an upstanding adult citizen, I of course self-criticize the youthful indiscretions of my past; no need to drag me to a struggle session. Aside from the thrill of being chased and the glory of seeing my signature scrawled all over the city, there really was no point to our graffiti. We referred to ourselves as writers though our tags were illegible to laypeople. Others called us street artists, but there was nothing artistic about it. It was raw vandalism, spray-painting instead of smashing stuff; a teenaged middle finger to authority.

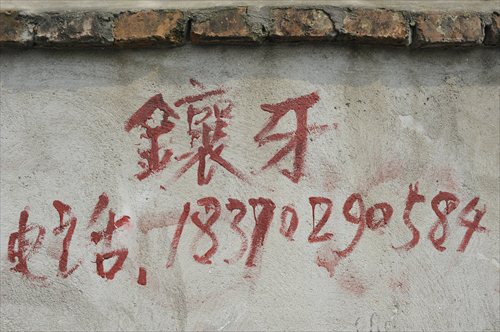

Dentures ad hand-painted on a brick wall Photo: Tom Carter/GT

When I first arrived in China over a decade ago, I was admittedly intrigued by the sight of so much vandalism here. This wasn't street art, however, but hand-styled advertisements for services ranging from recycling to sexual disease treatments to fake invoices. The vandals scribbled, sprayed, stamped or stuck their adverts on public walls, audaciously along with their phone numbers. In my reformed mind, doing so was just begging to be busted, but they never got caught. They proliferated far beyond what any graffiti crew in Los Angeles or New York City could get away with because there was an actual demand for their utilitarian tagging.

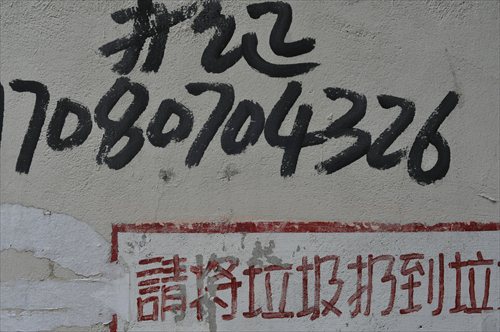

Air conditioner repair ad at a residence Photo: Tom Carter/GT

Ten years on, the advent of China's tech revolution has made such defacement largely irrelevant. Subsequently, the posses of peasants who were once paid to walk around the city all night writing phone numbers on walls have mostly abandoned their trade. Though you'll sometimes see stamps and stickers in bathroom stalls or alleyway communities, xiao guanggao ("small ads") are now a dying art form in urban China. With this in mind, this tagger-turned-photographer recently set out to pay tribute to the last few illicit ads that still exist around Shanghai.

Ad for fake official documents (diplomas, drivers' licenses, etc.) Photo: Tom Carter/GT

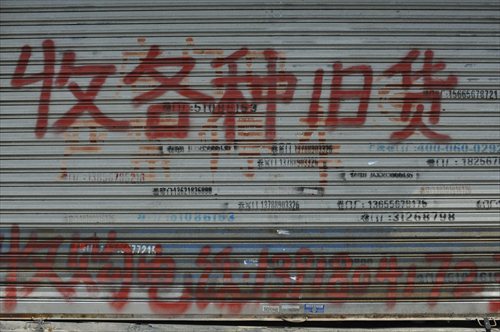

Recycling secondhand products ad spray-painted on shutter Photo: Tom Carter/GT

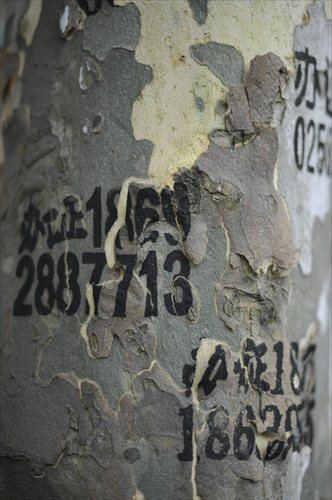

Fake accreditation ads stamped on a tree Photo: Tom Carter/GT

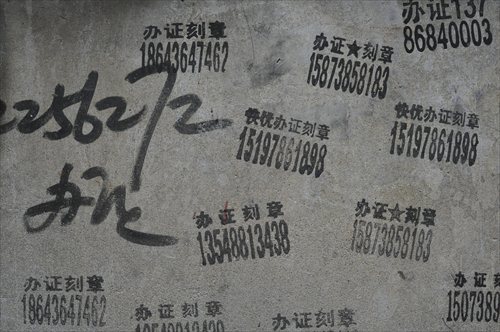

Stamps and seals ads stenciled all over a wall Photo: Tom Carter/GT

Newspaper headline: Chinese graffiti