Illustrations: Lu Ting/GT

Last week, news that two embezzlers from Shanghai's prestigious Fudan University asked for lenient punishment in the second hearing at Shanghai No.1 Intermediate People's Court provided food for thought among the public.

Huang Aimin and Ao Hong, the former deputy and former director, respectively, of an animal laboratory at Shanghai Medical College of Fudan University were sentenced to jail terms of 12 years and 10 years after the first court hearing. They admitted embezzling a total of 1.47 million yuan ($226,852) between 2008 and 2012. Ao returned 300,000 yuan in 2013 after being investigated while Huang did not return his money.

This case is part of China's wide-sweeping anti-corruption campaign, which has seen the Communist Party of China Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) send inspection teams to State owned enterprises, government departments and academic institutions across the country.

Fudan University was inspection by the commission in 2014 and later that year was found to have made inappropriate use of scientific and research funds as well as graft related to its Jiangwan campus infrastructure project that resulted in safety hazards. The university said that the employees involved in the embezzlement and graft had been transferred to the juridical department.

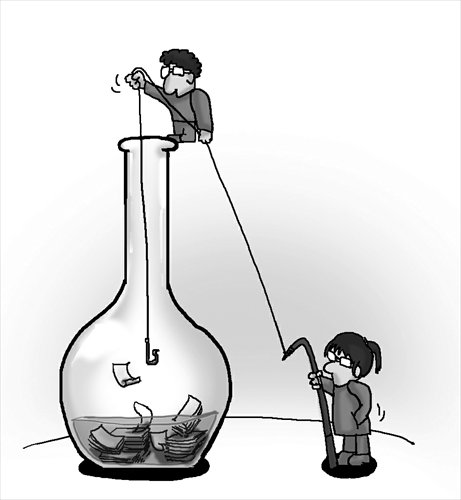

Ao, 47, female, with a doctor's degree, divorced, mother of an 18-year-old daughter, was the then-director. Huang, 48, a male technician, was the deputy head of the lab. They took advantage of loopholes in the university's reimbursement procedure by purchasing fake fapiao (invoices) from illegal traders commonly found standing around transport hubs like the Shanghai Railway Station.

Shanghai's procurator claimed that their jail terms were given in accordance with the current criminal law strictly based on the amount of money they had embezzled. Lawyers representing the defendants, however, claimed that their sentences are too long, as the so-called evidence of an "inside conference record" wasn't convincing and therefore could not support the trial. They also argued that part of their legal income earned from their jobs in the lab should not be calculated as an embezzled fund.

Both Ao and Huang were also given time to personally defend themselves. According to media reports, Ao chose to focus on her "miserable" personal life, complaining how she only earned a salary of 5,000 yuan, a meager income compared with Shanghai's high living costs. As a divorced woman, she said, her irresponsible ex-husband never helped raise their daughter, who needed tuition money for extra tutoring and who failed her gaokao (college entrance exam) due to the pressure of her mother's criminal trial. She also said she should be praised for returning her share of the stolen money and that China needs someone like her, as it's rare to come by a knowledgeable, cultivated Chinese doctor.

Huang also sang a sad song to the court, saying that he was suffering from chronicle kidney disease, that his son is mentally retarded and that he has to raise four senior family members, all which justified him taking the money for his own needs.

Had she been an illiterate countryside woman, Ao might have won sympathy from the judges and procurators for lenient treatment by acting like a "loser." But someone with so many privileges in life will find it quite hard to convince anyone that they were right in stealing public funds for personal purposes. The same goes for Huang, who really can't justify his theft just because he is "sick and tired."

Instead, if Huang and Ao and their team of lawyers really believe that they deserve lighter sentences, they should try to dig up prior case verdicts for embezzlement crimes involving civil servants and high ranking officials who served less time for more stolen money.

As China's central government moves to make criminal court decisions more transparent by making law data more accessible to legal professionals, including the 2014 establishment of an open-source national database of rulings, criminals and their lawyers will be forced to move away from the cliched "public sympathy" defense strategy that has made a farce of China's judicial system.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Times.