A scene from The Admonitions Scroll Photo: Courtesy of British Museum

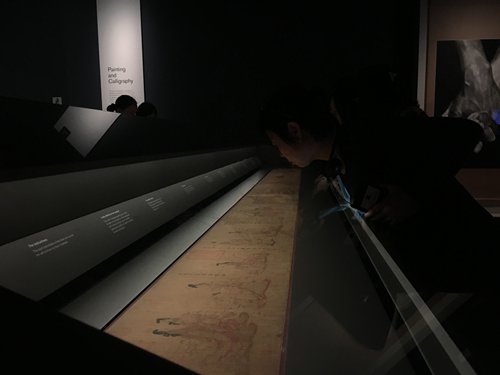

A visitor examines The Admonitions Scroll at the British Museum. Photo: Courtesy of British Museum

The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (The Admonitions Scroll) is being put back on display at the British Museum until August 16, giving visitors a rare opportunity to view one of the earliest extant examples of Chinese painting on silk.

The Admonitions Scroll is traditionally ascribed to Gu Kaizhi (345-406), a court artist who worked in Nanjing during the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) and who was known as the father of Chinese classical figure painting.

Part of the British Museum collection for more than a century, the painting on display is believed to be a fifth to eighth century copy of Gu's original work. It has been executed in a fine linear style that is typical of fourth century figure painting.

The Admonitions Scroll was originally used to educate ladies at court on how to behave according to Confucian principles. It illustrates a poetic text composed by the poet-official Zhang Hua (232-300).

There were originally 12 scenes depicted on the scroll at the British Museum, but three were lost at some point before it entered the museum's collection in 1903, leaving only nine remaining.

Setting the example

The nine scenes on The Admonitions Scroll represent exemplary acts of historical palace ladies or address the daily life and proper attitude expected of a court lady.

The scroll's message regarding good conduct for ladies at court draws on virtues associated with Confucian thought, such as humanity, righteousness, loyalty and respect for one's parents, husband and the emperor.

The first surviving scene is known as "Lady Feng and the Bear." Lady Feng was the consort of Emperor Yuan, who ruled during the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220) from 48BC to 33BC. In the scene, Feng and two palace guards place themselves in the path of a bear to protect the emperor, while another consort ignobly flees for her life.

The "Attending to Appearance" scene shows a court concubine grooming herself with the help of her maid. The concubine wears a long-sleeved wrap over robe while the maid wears a separate skirt, wrap over top and an elaborate hair ornament. The accompanying text emphasizes that cultivating one's inner self is as important as one's external appearance.

"The Rejection" scene depicts the emperor turning away from his consort, the text explains that by thinking she is his favorite, the consort in fact has lost the emperor's favor.

The Admonitions Scroll has been owned by emperors such as Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and the Qing Dynasty's Qianlong Emperor, as well as private collectors, many of whom stamped the painting with their seals or added inscriptions to the scroll. The earliest seals and inscriptions on this painting can be traced back to the eighth century.

Adding seals and inscriptions to a work of art was a traditional way of showing respect, and has proved useful for documenting a work's history as it passed from collector to collector through the centuries.

In 1899, during the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, the painting was acquired by an officer in the British Indian Army who sold it to the British Museum in 1903.

Around 1914, the scroll was mounted on panels and the painting was separated from the inscriptions. The decision to mount the ancient rolled hand scroll as a flat painting proved to be the right one given the brittle nature of the painting and its silk canvas.

Preserving beauty

The scroll is displayed in a state-of-the-art display case in Room 91a, which was designed for both long-term storage and periodic display. Since 2014, the painting is only put on display for a short period of time due to its extremely fragile condition.

The case glass cover has been placed at a 45 degree angle to allow closer viewing. Two hand-drawn internal blinds have also been installed so that the interior of the case can be blacked out completely if needed.

It has been a great challenge to preserve a work of art that is in such a fragile condition. The silk support is very worn and has been repaired through the centuries in many places, while the paint has cracked and begun flaking over time.

The British Museum has been researching how to better preserve and restore the painting for the past six years. In the summer of 2013, the museum invited academics and experts from around the world to discuss the best way to restore it.

In early 2014, Qiu Jinxian, senior conservator of Chinese paintings at the British Museum, put her 42 years of painting restoration experience to the test by working on The Admonitions Scroll.

Qiu told the Global Times that it took her two months of uninterrupted work with her assistants to restore the scroll to a more presentable state.

"It can easily go another 100 to 200 years without needing further repair," Qiu told the Global Times, adding that she used traditional materials, pigments and techniques during the restoration.

The display area is approximately four meters long, with the painting shown on one side of the display case and the seals and inscriptions on the other. The level of ambient light in the gallery is kept low in order to better protect the artwork.

Although this light sensitivity means the scroll can only be displayed for eight weeks out of the year, the museum has made digital copies available for long-term artistic appreciation.

According to Joanna Kosek, head of the Pictorial Art Conservation Department at the museum, the Google Art Center digitized the scroll in 2015. Viewers can now go online to the Google Arts & Culture web page to view the painting. They can even zoom in on the painting to examine the work in further detail.