Zhang Yueran Photo: Courtesy of Beijing Xiron Books Co, Ltd

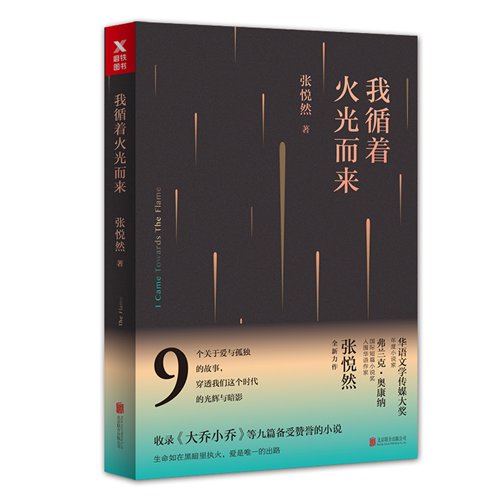

I Came Towards The Flame Photo: Courtesy of Beijing Xiron Books Co, Ltd

Chinese writer Zhang Yueran has long been an icon of 1990s pop fiction in China, a genre that has long been dismissed as fluffy nonsense by most serious literary scholars. But the 35-year-old female writer seems to be looking to grow beyond that label with a series of stories focusing on realism and social issues.

During a promotional event for her new book I Came Towards The Flame, Zhang sat down with renowned Chinese and foreign literary veterans such as Su Tong, Anna Gustafsson Chen - the Swedish translator behind Mo Yan's Nobel-winning work, and Taiwanese novelist Zhang Dachun to talk about her evolving outlook on writing.

Reflections of urban life

Featuring a more realist edge and a cruder yet poignant style that sets it apart from her past works, Zhang's new book tries to tackle the troubled sexual, marital and familial bonds that young Chinese today must deal with via nine short stories.

One of the stories that were discussed the most at the event is Daqiao and Xiaoqiao, a gloomy story about an urban Chinese family set during the one-child policy era. First published in Harvest - one of China's leading serious literature magazines, it has premiered works by some of China's best-known contemporary writers such as Mo Yan and Yu Hua - in February, the story sparked widespread discussion among critics, some calling it "a brave reflection on a social issue that the country is not yet ready to talk about."

In the story, the family of three begins to fall apart after Xiaoqiao - an "unplanned" child- survives a third-trimester induction abortion. The father, a public school teacher, gets fired for violating the one-child policy, while the mother is forced to go back to work to support the family.

Listing the breathtaking story as her top three favorites in I Came Towards The Flame, Chen, who attended the event via video call, called the story both convincing and heartbreaking. She stated that she saw the story as an attempt to explore China's increasingly material culture and the insurmountable gaps between the rich and poor in modern China.

However, Zhang partially disagreed with this assessment.

"Actually, I don't purposefully depict class in my stories," Zhang said, going on to explain that interpersonal communication is one of the main themes that she tries to express in her stories.

In addition to her observations, the Swedish translator noted that the depiction of modern Chinese city life in the story as well as the other eight had great potential for success in the international market.

"The Chinese literature works that Western readers are most familiar with now are still works written by the generation of writers born after the 1950s, like Yu Hua and Mo Yan," Chen said.

"And due to the fact that most of them were born to rural families, many of their stories take place in rural areas," she noted.

"Urban Chinese stories are rare in the foreign market."

The other way around

Besides Zhang, recent years have witnessed many other post-1980 pop fiction writers turn to serious literature, such as Zhou Jianing and Di An. Many of their works have been published in the country's top mainstream literature magazines.

This trend seems to indicate that serious literature circles are beginning to embrace these writers as well as the large number of young fans that support them, industry analysts noted.

First rising to prominence through the New Concept Writing Competition held during the 1990s and 2000s, the most influential pop literary event dedicated to discovering young Chinese writers, these writers were once criticized for their grandiose yet hollow writing styles as well as plots there were out of touch with reality.

"For me, it was painful to abandon my old writing style," Zhang admitted at the event.

"But I managed to grow out of this style. I think trying to rid of this style was actually a good thing as it has helped make me more confident."