METRO BEIJING / METRO BEIJING

Artist Han Shuo talks about his thoughts on freehand figure traditional Chinese painting

Artist Han Shuo Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

I am from Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province and have been doing Chinese paintings for decades. In this article, I want to share my perspective and thoughts on Chinese freehand paintings in China.

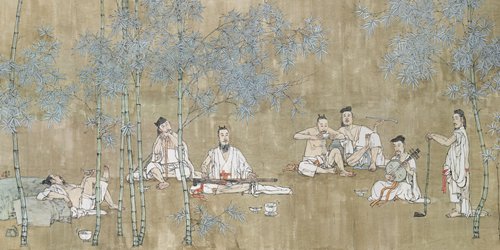

Zhu Lin Qi Xian Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

The shaping of an image comes firstChinese painting is like other kinds of art forms in terms of shaping an image. The image of a flower-and-bird painting is a flower, bird, fish or insect. The image of a landscape painting is a mountain, tree, cloud or water, and the image of a portrait is the figure.

Broadly speaking, the composition of a painting, the ink penetration and even the abstract painting has to face the problem of how to shape an image. We usually require that ink and brush strokes have quality lines and charm, as both are crucial to Chinese painting. They embody the beauty of Chinese painting and are important signals for whether the artist's skill is mature or not.

Without the shaping of an image, the painting has no soul. A piece of artwork is perfect only when painting integrates with the shaping of an image.

Freehand figure painting is not an exception. Many artists don't care about the shaping of an image when they are painting. They have no training and no awareness of how to do it. Once, there was a figure painter who saw a sketch of one of my paintings and proudly stated that he never sketches. But when you looked at his paintings you would know whether he should have sketched or not.

The viewers of your painting only care whether your painting is good enough. I have some artist friends who can make their sketches so delicate that the sketches themselves can be a piece of perfect artwork.

Regardless of how one creates a painting, his aim is to exert his strong points to make the best artwork. There is no way which is superior or inferior to another.

Nan Chang Qi Yi Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

The charm of brush and ink paintingsWe often hear that in shaping an image, Chinese paintings cannot catch up with oil paintings, and freehand brushwork paintings are also slightly inferior to fine brushwork paintings because they cannot express as much technique as oil paintings or fine brushwork paintings.

I don't agree with this saying because one standard cannot apply to so many different things.

Both freehand brushwork and fine brushwork paintings have their own charm. The charm of brushwork paintings lies in its ease, verve and ink penetration, which does not go against exquisite technique and details. Take the great freehand brushwork of the famous artist Qi Baishi for example; although there seems to be inadvertence in the gorgeousness of his artwork, it is hard for you to imagine how meticulous he is when creating.

In his Chinese cabbage painting, Qi would note down how much light ink and heavy ink he used in drawing the cabbage leaves and how many light ink lines he used to draw the cabbage stalk. When he drew a landscape with a pavilion on a mountain, he marked on the sketch whether the position of the pavilion needs to be moved to the upper part of the painting a little.

The small position shift can be ignored in a landscape painting; however, he is still meticulous about every detail of his paintings.

Although Qi is quite careful with his lines and each drop of ink he uses, what you see in his paintings is not constraint, but great flexibility. The paintings of China's excellent freehand brushwork painters, from Liang Kai to Zhu Da and Pan Tianshou, are so classical that any small change is not allowed to damage their beauty. Who can say that such paintings are not delicate and exquisite?

There are a lot of excellent artworks flooding national art exhibitions in recent years, but I have found that the freehand brushwork paintings, especially the freehand figure paintings, are still relatively weak.

One important reason is that there are many difficulties in shaping an image for a freehand brushwork painting. The painter has to handle his brush strokes well along with how wet, dry, thick or light the ink is.

If he does not manage it well, he cannot undo it. When a painting has a lot of figures and the scene is complicated, only experienced painters can handle it. It is not uncommon to see paintings stained due to a lack of skill.

Zhong Kui Jia Mei Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

Make the artwork vibrantIn the mid-1960s, artist Fang Zeng wrote a brochure titled How to Draw Ink Figure Painting, which was sold at only 0.42 yuan ($0.07). It was the best textbook for Chinese freehand figure painting learners at that time and influenced a whole generation of artists. Decades passed, and the brochure has fulfilled its mission. Fang's artwork also went through several changes and returned to the public with a pretty new outlook.

Chinese art nowadays is in the multidimensional era. How should freehand figure painters meet the new era?

I am often invited to all kinds of exhibitions, and I have found that very few young people view the older painters' artwork. There seems to be a gap between the young people and the older painters. Older painters are more experienced, and younger painters usually have sharp thoughts and lots of passion in creation. If the two parties can communicate more and learn from each other's strong points, their artwork will be complementary.

I know many artists who are in their 70s and like to make friends with young artists. They usually talk about fresh ideas. The older artists are willing to accept new thoughts and embrace new things and concepts. Their artwork features strong characteristics of the new era and is full of energy.

Viewers say that these old artists' artwork is like those created by young artists, but most young artists might not achieve the amount of skill reflected in their paintings.

People's experiences vary, and their ways of learning painting are different. But everyone can find a suitable road and walk it diligently. When I was very young, I did not receive tertiary education. I drew paintings while working.

Over the past decades, I have faced a lot of difficulties and confusion when drawing my artwork. The challenges range from selecting topics and shaping a figure's image to all kinds of technical issues in my paintings. My ability to solve problems has improved significantly through practice.

As long as one persists, every road can lead to the summit of glory. But one should see both the positive and negative sides of their road clearly. Everything has two sides, like a coin.

Take attending an academy of fine arts for example; it is a good thing on one side because you can get lots of practice and solid basic knowledge, but on the other side your creativity might be relatively weaker.

Mu Ke Zhai Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

Pan Si Dong Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

The spirit of freehand brushworkAn important standard to tell whether an artwork is good is whether the painter has his own personality, whether he breaks through the clichés, whether he has his unique "language" or perspective, whether the artwork represents the era and whether it has soul.

In recent years, there have been heated discussions about the spirit of freehand in the field of Chinese paintings. It is proposed that fine brushwork paintings should also have a similar spirit to that of freehand. The spirit of freehand is meaningful for freehand brushwork paintings. The depth of the spirit is dependent on the depth of the painter's thoughts.

What one depicts comes from one's life and painting experience. Only when a painter has both good thoughts and skills that can convey those thoughts, will they be able to create a piece of perfect artwork that has "spirit."

The opinions on the spirit of freehand are divided. I don't mean to argue about it. I just think that putting the "spirit" of freehand into a painting will make it different from those outdated and repetitive paintings, and I embrace the idea of gifting a painting with soul.

Xi Xiang Ji Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo

Introduction to the artist:Han Shuo was born in 1945 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. He graduated from the department of Chinese painting at Shanghai University. Han is a national-level artist, a director of the China Artists Association, a member of the Chinese Painting and Art Committee of the China Artists Association, vice president of the Chinese Painting Institute, and a director of the Shanghai Artists Association's Chinese Painting and Art Committee. He is also an adjunct professor at both Shanghai University and Shanghai Normal University's College of Fine Arts.

Artist Han Shuo Photo: Courtesy of Han Shuo