IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

GQ article refuted after implying Chinese government is behind theft of treasures overseas

Robbing the truth

○ GQ published an article titled "The Great Chinese Art Heist," implying China ordered the thefts of looted relics from Western museums

○ The general manager of China's Poly Culture Group, Jiang Yingchun, says the article is nonsense

○ Since 2008, China's National Cultural Heritage Administration has reclaimed around 4,000 looted relics

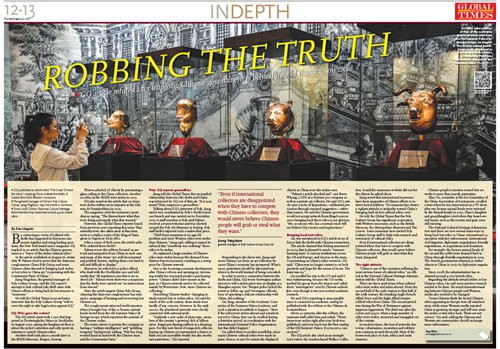

A visitor takes photos of four of the 12 bronze animal heads looted from the Old Summer Palace by foreign troops, on August 8. The bronze animal heads, temporarily displayed in Zhaoqing, South China's Guangdong Province, represent the animals of the Chinese zodiac. Photo: VCG

In the article published on August 16, writer Alex W Palmer tried to prove that the State-run conglomerate China Poly Group and some Chinese elites devoted to bringing back stolen or lost relics to China are "cooperating with the Communist Party of China."

Jiang Yingchun, the general manager of Poly Culture Group, said the GQ report's attempt to link cultural relic theft cases with China's efforts to bring back its lost treasure is "nonsense."

He told the Global Times in an exclusive interview that the Poly Culture Group "will reserve the right to take legal action against GQ."

GQ: Who gave the orders?

Another theft took place a month later in the KODE Museum, Bergen, Norway.

Thieves plucked 56 objects by penetrating a glass ceiling in the China collection. Another 22 relics in the KODE were stolen in 2013.

GQ also noted in the article that 22 items were stolen within seven minutes at the Château de Fontainebleau in 2015.

The magazine cited the museum's president as saying, "The thieves knew what they were doing and exactly what they wanted."

However, this Global Times reporter found from previous news reporting that some Thai artworks were also taken away at that time, such as a replica crown of the King of Siam, given to Napoleon III in 1861.

After a series of theft cases, the article asks: Who ordered these thefts?

Palmer wrote the robbers focused on artwork and antiquities from China in each case, and many of the items "are well documented and publicly known, making them very hard to sell and difficult to display."

Moreover, he referred to a police official who dealt with the Stockholm case and told media that "all experience says this is an ordered job." Palmer wrote there was a suspicion that the thefts were carried out "on instructions from abroad."

Next, the article targets China Poly Group, claiming the State-run conglomerate has initiated a campaign of locating and recovering lost Chinese art.

The conglomerate attracted world attention when it bought four of the 12 bronze animal heads looted from the old Summer Palace by foreign troops, which represent the animals of the Chinese zodiac.

The writer strives to portray the company as having a "military-intelligence" and "peddling weapons" background, adding, "Poly has long worked hand in hand with the Chinese state and the Communist Party."

Poly: GQ reports groundless

Jiang told the Global Times that an implied relationship between relic thefts and China was fabricated by GQ out of thin air. "It is nonsense! Their suspicion is groundless."

Talking about GQ's interview of Poly, Jiang said it was coordinated by Poly's North American branch and was carried out in November 2017. A staff member at Poly said Palmer received a warm welcome and was showed around the Poly Art Museum in Beijing. Poly staff hadn't expected such a malevolent piece.

"Theft from museums is an age-old problem and more Western relics were stolen than Chinese," Jiang said, adding it cannot be inferred that "somebody was ordering" those relics to be stolen.

He explained a large number of Chinese relics were stolen because the demand from Eastern buyers increased, resulting in a rising price for Chinese artwork.

Due to the booming economic development after China's reform and opening-up, increasing wealth has increased people's purchasing power. "Chinese didn't have money in the past, so Chinese artwork used to be collected mainly by Westerners. Now, more Chinese are collecting."

Describing Chinese leaders' changing attitude toward lost or stolen relics, GQ said for much of the 20th century, those items were hardly of any concern. However, by the early 2000s, the plundered artworks were closely connected with national pride.

"Suddenly a new cadre of plutocrats - members of the country's growing club of billionaires - began purchasing artifacts at a dizzying pace. For this new breed of mega-rich collector, buying up Chinese art represented a chance to flash not just incredible wealth but also exorbitant patriotism," GQ reported.

Responding to the above text, Jiang said more Chinese are keen on art collection because China's economy has prospered. What's more, patriotism should be advocated anywhere in the world instead of being concealed.

In order to prove a connection between the thefts and China, GQ wrote Norwegian authorities were told a stolen piece was on display at a Shanghai airport, but "Bergen police lacked the power to follow up, and Norwegian officials, wary of upsetting a delicate relationship with China, did nothing."

Liu Yang, member of the Academic Committee of the Summer Palace Academy, said such a situation is unlikely to happen. "Even if the relics were stolen abroad and somehow moved to China, they can be recalled during a detection period, in coordination with the International Criminal Police Organization, but that didn't happen."

Liu added there is another possibility, since many Chinese cultural relics were made in pairs. Hence, it can't be certain the displayed objects in China were the stolen ones.

"Palmer's article shocked me!" said Kevin Whong, a CFO at a Fortune 500 company as well as a private art collector. He said GQ's article uses a tactic of hypnotism - subliminal persuasion through repeated suggestion - rather than reason. He said the Chinese government would not accept artwork from illegal sources since bringing back those relics is not glorious. "Me, or anyone who has a normal mind will not believe GQ's tactics and implications."

Bringing back lost relics

Liu was mentioned in GQ's article in an effort to link the thefts with Chinese researchers.

The article claimed that Beijing announced in 2009 that it planned to send a "treasure hunting team" to various institutions across the US and Europe, and Liu was in the team. Commenting on China's relics research, GQ said, "China was no longer content to sit back passively and hope for the return of its art. The hunt was on."

Liu recalled his trip to the US and said it was embarrassing, because the US media tracked his group from the airport and called them "investigators" sent by Chinese authorities, even though it was just normal academic research.

He said GQ's reporting is unacceptable since it connected an academic catalog he published with the robbery at the Château de Fontainebleau.

About 30 minutes after the robbery, the museum staff called him and asked, "These items were stolen right after your book was published, and your book was the first catalog of the Old Summer Palace. Do you see a connection?"

The GQ article also cited as an example Liu's visit to the London-based Wallace Collection. It said the museum's website did not list the objects he asked about.

Jiang noted that international museums have been supportive of China's efforts to retrieve looted artifacts. "No museum has shown a vigilant attitude or antipathy toward China's bringing back its lost cultural relics, ever."

He told the Global Times that the Poly Culture Group has significant cooperation with Western museums, such as the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum and The Louvre. Some museums have invited Poly Culture Group staff to help with research and restoration of cultural relics.

Even if international collectors are disappointed when they have to compete with Chinese collectors, they would never believe Chinese people will grab or steal what they want, Jiang said.

The right attitude

"China is one of the countries suffering the most serious losses of cultural relics," an official at the National Cultural Heritage Administration told the Global Times.

There are three peak times when cultural relics were stolen and taken abroad. From the second half of the 19th century to first half of the 20th century, the invading Anglo-French Allied Force and the Eight Allied Armies robbed relics from China. The second period was during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. The third was after the 1980s and 1990s, when a large number of relics were stolen, excavated and smuggled out of the country.

In modern times, the loss of artworks due to war, colonization, excavation and robbery was common around the world. Most of the losses took place in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Chinese people's emotion toward lost artworks is more than merely patriotism.

Zhao Yu, counselor at the Art Committee of the China Association of Auctioneers, recalled a time when he was interviewed on a TV show after two bronze animal heads were returned by the Pinault family in 2013. Zhao's daughter and granddaughter cried when they heard several heads, such as the rooster and goat, were still missing.

The National Cultural Heritage Administration said there are now several main ways to bring back lost relics to China: international cooperation with law enforcement, international civil litigation, diplomatic negotiations, friendly negotiations, or acquisitions and donations.

For example, the bronze animal heads of the rat and the rabbit were donated back to China through friendly negotiations in 2013. The French government returned 32 stolen objects to China in 2015 via diplomatic negotiation.

Since 2008, the administration has reclaimed around 4,000 looted relics.

Regarding the attitude toward stolen or lost Chinese relics, Liu said more precise research needed to be done. He noted misunderstanding between Chinese people and Western media also needed to be changed.

"Some Chinese think the looted Chinese relics appearing in Europe were all snatched away, while some Western media reported China is growing stronger and will now seize the stolen or lost relics back. These are not correct," Liu said, adding the Chinese and Western art communities should exchange more information.