Resumption of Gaokao propelled China’s economic take-off

Resumption of talent selection system propelled country’s economic take-off

Students walk out of a school where they had sat a 2019 Gaokao exam. Photo: IC

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China. During the past seven decades, China has endured a certain period of volatility, but Beijing soon devised solutions to end turbulence and bring the economy to a fast-track of development. In the education sector, the resumption of the Gaokao in 1977 was a watershed event. The Global Times recently talked with those who sat the 1977 Gaokao and discussed how it has changed China.

This summer, millions of high school students across China are waiting anxiously for their admission results for Chinese universities based on the scores they receive from their Gaokao, a high-stakes exam officially known as the National College Entrance Examination.

Some 10 million students took the college entrance examinations from June 7 to June 9, fulfilling their dreams to pursue higher education in China's top universities through hard work and grueling exam preparation.

This year marks the 42nd year since the resumption of the Gaokao, a talent-selection mechanism that has been delivering high-quality college graduates to empower China's rapid economic and social development.

In 1977, the first year the Gaokao was restored after a decade-long hiatus due to the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), around 5.7 million people — including high school graduates, farmers and factory workers — took the exam. The exam was the world's largest in terms of participants and competition was very fierce at that time, with less than 5 percent of candidates being admitted to university, the lowest admittance rate in China's history. This is particularly shocking when compared with the current rate of roughly 70 percent.

Liu Tiegen, director of the Institute of Optical Fiber Sensing under Tianjin University, is part of the cohort that sat the 1977 Gaokao that changed China.

Recalling the exam, the 65-year-old man described the resumption of the Gaokao as a "watershed" event in the history of China's education that signaled the country's educational system was back on the right track. The standardization of the system is also regarded as a precursor to China's reform and opening-up in 1978, which then nurtured a pool of talent that drove the country's economic take-off for years.

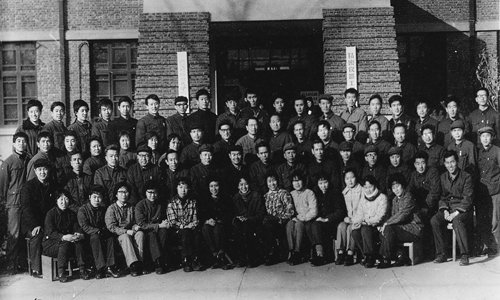

Graduation photo of Liu Tiegen and his undergraduate classmates at Tianjin University. Photos: Courtesy of Liu

Historic momentIn 1974, Liu graduated from high school in North China's Tianjin Municipality and was then sent to the countryside to work as an "educated youth (zhiqing)" at a settlement office in a rural commune.

At that time, getting into college required a recommendation from the Communist Party units, and only those who achieved high political scores in the countryside and had a "good" family background, such as workers, peasants and soldiers, were qualified for such a recommendation. Liu himself had been in queue for the recommendation for several years before 1977.

Desire for knowledge was common for Liu's generation as chances to receive higher education were very meager.

"I wanted to learn, so I also brought notes and books from high school with me, reviewing them and having discussions with other 'educated youth' during my spare time," Liu told the Global Times on Tuesday.

Never had he, nor thousands of "educated youth" sent to the countryside, imagined a resumption of the Gaokao until the news broke out suddenly in October 1977. "It was a bleak autumn in 1977 [when we heard the news], but my colleagues and former classmates were overwhelmed by joy and excitement. It sounded so unreal."

In late 1977, then-Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping made the historic decision to reform the talent selection scheme and reinstate the Gaokao.

Liu and his generation, luckily, got a ride on the first train.

Everything was rushed at that time. Liu had less than two months to prepare, and he squeezed as much time as he could from his regular workload to study day and night, cramming knowledge from middle school and high school.

"My preparation was far from sufficient, but I sometimes comforted myself by thinking: I only have a three-year gap [between high school and] taking the exam, and I should be in a advantaged position compared with those who have gaps of five years or more," Liu joked.

Unlike the college entrance exam, which now is generally held in early June, it was a cold and snowy winter when the Gaokao was held at a middle school in Tianjin, roughly 20 kilometers from Liu's workplace in 1977. He got up at 6 am and rode a bicycle for two hours to take the exam.

"The roads were slippery and bumpy, but I was in high spirits… I knew the chance to attend college was within reach," Liu said. He was 22 years old at the time, while some candidates were in their 30s or 40s.

Every province had its own exam papers. During the two days, Liu took three exams: Chinese, Politics and Science — including mathematics, physics and chemistry, with a total score of 450 points.

"I didn't perform well in Politics because the textbook and materials were rare, and I could not get them to review. But in Chemistry I did quite well. I was anxious and even thought that I might need to take the exam again next year," Liu recalled. He even had a plan B to work as a maintenance worker at an automobile factory in Tianjin if he did not secure a college position.

Liu Tiegen and his undergraduate classmates at Tianjin University on the 30th anniversary of their graduation on January 1, 2008.

The 1977 generationDespite his worries, the results were beyond Liu's expectations.

Liu was admitted to Tianjin University, which he said was a "life-changing moment" for his family. He then pursued a master's degree and a PhD degree at Tianjin University. As most universities were short-handed at the time, Liu remained at the university after his graduation to serve as a professor of subjects related to optoelectronics engineering.

Liu, calling himself a witness of how changes in China are building up and gaining momentum, said his career's development has been in tandem with China's technology rise during the past decades.

Liu now serves as the chief scientist of a national optical fiber sensing project under the National Basic Research Program (973 Program) and the director-general of the Association of National Optical-mechanical Technology and System Integration under China Instrument and Control Society. He also enjoys a special allowance of the State Council, China's cabinet, a subsidy only high-level Chinese technicians are entitled to.

"When I began research in optoelectronics in the 1980s, we were just reading theses written by foreign scholars and following their footsteps, but now we devote ourselves to developing innovative, researches," he explained.

His team applies for more than 10 patents every year now, with world-leading breakthroughs in areas such as fiber optic pressure sensing and fiber optic gas sensing. Prior to 2000, the total number of patents Liu's team had applied for was below 10.

Like Liu, the other students of the 1977 cohort, or the first college graduates after the end of an extremely turbulent period, have now become pillars of China's economy, in areas spanning politics, technology, science, medicine and culture. Some are esteemed officials and directors, including Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, who was enrolled in Peking University after sitting the 1977 Gaokao, and film director and producer Zhang Yimo.

Together they guided the Chinese economy, which was in ruins back in the 1970s, through modernization, reform, and opening-up, to become the world's second-largest powerhouse.

Liu Tiegen (right) works with a colleague in a library. Li Xuanmin/GT

Modern contextWithout a doubt, the 1977 Gaokao played a pivotal role in underpinning China's economic growth. However, given the head-to-head global tech competition and China's industrial upgrade and transformation, industry observers have called for another overhaul in the educational system to better propel China's economy.

Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the Shanghai-based 21st Century Education Research Institute, told the Global Times on Tuesday that under a modern context, the Gaokao's role in the educational system should be revised from "a baton of examination" to "a server" that helps universities assess students during the enrollment process.

"China now needs innovative and high-quality talent to gain a firm foothold in the global race, but it is hard to create such graduates under the exam-oriented system. Gaokao results should only be a reference for higher education admissions," Xiong explained.