○ Danzhai county, Southwest China's Guizhou Province, one of the poorest areas in China, eradicated poverty by developing tourism and promoting local culture

○ Many Miao women including the elderly have earned their first company salaries with the help of the poverty alleviation project

○ US researchers see much to learn from the Danzhai model and encourage the US to be open-minded

Since 2014, Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda Group has built a vocational college and tourist village and established a fund in Danzhai to help address poverty in the region. The group has invested 2.1 billion yuan ($310 million) so far.

In return, the county has attracted investment and tourists, creating tax revenue of 270 million yuan and stimulating local GDP growth of 1.2 percent over the past four years. In April, the People's Government of Guizhou Province announced that Danzhai county had eradicated poverty.

This is a small part of China's massive goal to lift all of its 1.4 billion people out of poverty by 2020. Government officials at all levels in China have been racking their brains to reach this goal over the past few years.

According to the Xinhua News Agency, from 2013 to 2017, a total 9.28 million Chinese were lifted out of poverty - roughly the population of Hungary.

However, there are doubts about whether those villages and townships that have been lifted out of poverty can survive and develop in a sustainable way.

For many people who visit Danzhai, it certainly seems that the county has made it.

First salary

Dressed in traditional Miao clothes, 66-year-old Ahua picked tea leaves in the Danzhai Poverty Alleviation Tea Garden. Moving with an obvious stoop, she wore a black bag on her back that contained her lunch.

The tea garden has helped local tea growers increase their incomes and expand market channels, while also providing training and jobs to locals.

Originally from Pu'an, Sandu Shuizu Autonomous county, Ahua moved to Danzhai, nearly 40 kilometers away, so her grandson could go to school there.

A farmer back in Pu'an, she got by on what she could sell herself, not receiving a single cent from any company or organization.

"I feel happier picking tea leaves here, since I can chat with my friends and sisters instead of farming alone at home," she told the Global Times, noting that many villagers migrated to Danzhai after the poverty alleviation project was launched there.

For another group of local Miao women, the changes they and their family have enjoyed go far beyond the monetary and better living conditions.

Source of pride

In the tourist village at Danzhai sits a shop called Village Story. Dark blue clothing and bags decorated with various patterns in white are on display in the shop.

Wang Jianqi, 30 years old, was busy using a tiny axe-shaped knife to draw various designs in beeswax on a canvas bag that she would later sell for 99 yuan. Wang was dressed in traditional clothing she made herself. Blue with white designs, the clothes were made using an ancient Miao wax-resist dyeing technique.

Similar to the canvas bag, the clothing is drawn on using beeswax and then dyed deep blue, causing the designs covered in beeswax to spring forth from the background color.

Originating from as early as the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220), this type of wax-resist dyeing of cloth is an integral part of the Miao people's ancient culture and history. In 2006, the techniques of making these fabrics were listed in China's first group of national intangible cultural heritages.

The founder of Village Story, Yu Ying, has witnessed tremendous changes in the village since she first came to explore the local culture a decade ago.

"I remember 10 years ago, when I visited the villages for the first time, most of the people who welcomed me were men. I could feel their disdain and arrogance," Yu said.

Attracted by the beauty of the local culture, she decided to launch training projects to teach Miao women about marketing and exporting their cultural products to other parts of China, even abroad, so that the culture could thrive and continue to be passed on.

She told the story of Wu Ruqun, a woman who participated in Yu's training program three times.

"She loves embroidery so much… After following our project for two years, she became the main economic source in her family," Yu said.

While visiting Wu one time, Yu saw Wu's husband ask for some money. With the demeanor of a strict wife, Wu took out the money from her purse, counted it, and then gave the money to her husband.

In Danzhai, Yu also saw happy couples working together. She saw some men in the villages drawing patterns on the clothes with beeswax or dying the clothes; some even embroider together with their wives.

"In the big city, maybe we would say this is something only sissies would do, but in the villages, all I see is harmony between husband and wife," Yu noted.

One of the problems in poverty-stricken areas in China are so-called "left-behind children" - children left in the care of family members while their parents head off to big cities in search of work.

Some of Yu's staff used to have to leave their kids behind, but with this new source of income they are now able to stay at home and accompany their children.

"Allowing mothers to stay means having the men stay. It also means that the children and local culture can stay. No matter what methods we use, such as embroidery or developing tourism, as long as we retain mothers we can bring hope to others," Yu told the Global Times.

So far, more than 5,000 villagers have received training through Yu's program, while a total of 3,000 female embroiders have worked for Yu.

"I found what touched me is not only the beautiful craftsmanship, but the people… So if there is a little something that I can do for them, I will feel very happy," Yu said.

US learning from China

Danzhai's poverty alleviation project has attracted attention from US researchers.

Antonio M. Bento, a professor and director of the Center for Sustainability Solutions at the University of Southern California (USC), is one of them.

In late May, Bento brought his students to Danzhai to learn about its poverty alleviation programs. He was quite impressed by the work in Danzhai.

Bento said that one of the strengths of the Danzhai model is that it doesn't lift people from poverty by just giving them money, but by providing them with the jobs they need to make money themselves.

He noted that in the US income transfers are a very common way to deal with poverty, which is to use the tax system or other types of polices to transfer income to individuals.

"When I look in the US society, for example, much of the tension that existed around 2016 Presidential Elections was really the failure of the US society to come up with a vision for rural America. Under the lack of vision for rural America, the only way to deal with poverty in rural America was essentially by buying people out, by giving them cash transfers," Bento said, noting that by providing cash transfers, the government is actually not giving individuals a way to get out of poverty, because it will have to continue to subsidize them.

Justin Dewaele, a graduate student at USC studying urban policy who went with Bento to the village, said that he found it a pity that many people in the West disregard China's economic development models out of hand.

He said people should keep an open mind when trying to find solutions to complicated issues like poverty and rural development.

He said he intends to tell his friends that Danzhai has many creative models which have not been thought about carefully in the US, especially in the way that local culture is protected and promoted.

○ Many Miao women including the elderly have earned their first company salaries with the help of the poverty alleviation project

○ US researchers see much to learn from the Danzhai model and encourage the US to be open-minded

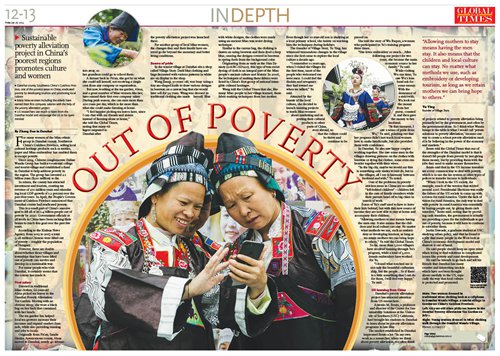

Two women dressed in traditional Miao clothing look at a cellphone in Danzhai Wanda Village, a tourist village in Southwest China's Guizhou Province. Photo: Li Hao/GT

For many women of the Miao ethnic group in Danzhai county, Southwest China's Guizhou Province, selling local cultural heritage products such as textiles, paper and Miao embroidery has enabled them to escape poverty.Since 2014, Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda Group has built a vocational college and tourist village and established a fund in Danzhai to help address poverty in the region. The group has invested 2.1 billion yuan ($310 million) so far.

In return, the county has attracted investment and tourists, creating tax revenue of 270 million yuan and stimulating local GDP growth of 1.2 percent over the past four years. In April, the People's Government of Guizhou Province announced that Danzhai county had eradicated poverty.

This is a small part of China's massive goal to lift all of its 1.4 billion people out of poverty by 2020. Government officials at all levels in China have been racking their brains to reach this goal over the past few years.

According to the Xinhua News Agency, from 2013 to 2017, a total 9.28 million Chinese were lifted out of poverty - roughly the population of Hungary.

However, there are doubts about whether those villages and townships that have been lifted out of poverty can survive and develop in a sustainable way.

For many people who visit Danzhai, it certainly seems that the county has made it.

First salary

Dressed in traditional Miao clothes, 66-year-old Ahua picked tea leaves in the Danzhai Poverty Alleviation Tea Garden. Moving with an obvious stoop, she wore a black bag on her back that contained her lunch.

The tea garden has helped local tea growers increase their incomes and expand market channels, while also providing training and jobs to locals.

Originally from Pu'an, Sandu Shuizu Autonomous county, Ahua moved to Danzhai, nearly 40 kilometers away, so her grandson could go to school there.

A farmer back in Pu'an, she got by on what she could sell herself, not receiving a single cent from any company or organization.

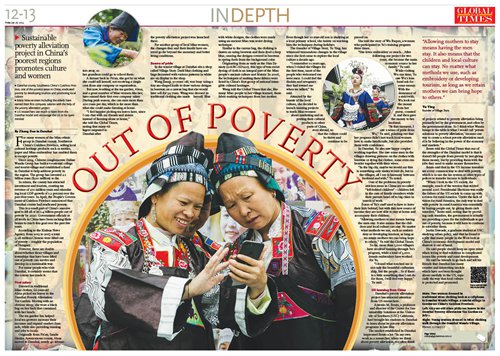

Young women dressed in Miao clothing walk through the Danzhai Wanda Village. Photo: Li Hao/GT

But now, working at the tea garden, Ahua and a great number of Miao women like her have earned their first ever company salary. During peak season, she can earn more than 200 yuan per day, which is far more than what she could make farming at home."I feel happier picking tea leaves here, since I can chat with my friends and sisters instead of farming alone at home," she told the Global Times, noting that many villagers migrated to Danzhai after the poverty alleviation project was launched there.

For another group of local Miao women, the changes they and their family have enjoyed go far beyond the monetary and better living conditions.

Source of pride

In the tourist village at Danzhai sits a shop called Village Story. Dark blue clothing and bags decorated with various patterns in white are on display in the shop.

Wang Jianqi, 30 years old, was busy using a tiny axe-shaped knife to draw various designs in beeswax on a canvas bag that she would later sell for 99 yuan. Wang was dressed in traditional clothing she made herself. Blue with white designs, the clothes were made using an ancient Miao wax-resist dyeing technique.

Similar to the canvas bag, the clothing is drawn on using beeswax and then dyed deep blue, causing the designs covered in beeswax to spring forth from the background color.

Originating from as early as the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220), this type of wax-resist dyeing of cloth is an integral part of the Miao people's ancient culture and history. In 2006, the techniques of making these fabrics were listed in China's first group of national intangible cultural heritages.

Wang Jianqi makes a canvas bag that will sell for 99 yuan. Photo: Zhang Dan/GT

Wang told the Global Times that she, like many Miao people in her village, learned these fabric-making techniques from her mother. Even though her 10-year-old son is studying at a local primary school, she insists on teaching him the techniques during holidays.The founder of Village Story, Yu Ying, has witnessed tremendous changes in the village since she first came to explore the local culture a decade ago.

"I remember 10 years ago, when I visited the villages for the first time, most of the people who welcomed me were men. I could feel their disdain and arrogance," Yu said.

Attracted by the beauty of the local culture, she decided to launch training projects to teach Miao women about marketing and exporting their cultural products to other parts of China, even abroad, so that the culture could thrive and continue to be passed on.

She told the story of Wu Ruqun, a woman who participated in Yu's training program three times.

"She loves embroidery so much… After following our project for two years, she became the main economic source in her family," Yu said.

While visiting Wu one time, Yu saw Wu's husband ask for some money. With the demeanor of a strict wife, Wu took out the money from her purse, counted it, and then gave the money to her husband.

Ahua, 66-year-old, picks tea leaves in the Danzhai Poverty Alleviation Tea Garden on July 1. Photo: Li Hao/GT

"At that moment, I saw a sense of pride from Wu," Yu said, pointing out that her program didn't just teach local women how to make handicrafts, but also provided them with confidence.In Danzhai, Yu also saw happy couples working together. She saw some men in the villages drawing patterns on the clothes with beeswax or dying the clothes; some even embroider together with their wives.

"In the big city, maybe we would say this is something only sissies would do, but in the villages, all I see is harmony between husband and wife," Yu noted.

One of the problems in poverty-stricken areas in China are so-called "left-behind children" - children left in the care of family members while their parents head off to big cities in search of work.

Some of Yu's staff used to have to leave their kids behind, but with this new source of income they are now able to stay at home and accompany their children.

"Allowing mothers to stay means having the men stay. It also means that the children and local culture can stay. No matter what methods we use, such as embroidery or developing tourism, as long as we retain mothers we can bring hope to others," Yu told the Global Times.

So far, more than 5,000 villagers have received training through Yu's program, while a total of 3,000 female embroiders have worked for Yu.

"I found what touched me is not only the beautiful craftsmanship, but the people… So if there is a little something that I can do for them, I will feel very happy," Yu said.

US learning from China

Danzhai's poverty alleviation project has attracted attention from US researchers.

Antonio M. Bento, a professor and director of the Center for Sustainability Solutions at the University of Southern California (USC), is one of them.

In late May, Bento brought his students to Danzhai to learn about its poverty alleviation programs. He was quite impressed by the work in Danzhai.

"In my own work as a researcher, when we think about poverty alleviation, we often think of projects related to poverty alleviation being primarily led by the government, and often by the government alone. So I think what Wanda brings to the table is what I would call 'private solutions to poverty alleviation,' because one way to create a robust poverty alleviation model is by believing in the power of the economy and markets," he told the Global Times in an e-mail.

Bento said that one of the strengths of the Danzhai model is that it doesn't lift people from poverty by just giving them money, but by providing them with the jobs they need to make money themselves.

He noted that in the US income transfers are a very common way to deal with poverty, which is to use the tax system or other types of polices to transfer income to individuals.

"When I look in the US society, for example, much of the tension that existed around 2016 Presidential Elections was really the failure of the US society to come up with a vision for rural America. Under the lack of vision for rural America, the only way to deal with poverty in rural America was essentially by buying people out, by giving them cash transfers," Bento said, noting that by providing cash transfers, the government is actually not giving individuals a way to get out of poverty, because it will have to continue to subsidize them.

Justin Dewaele, a graduate student at USC studying urban policy who went with Bento to the village, said that he found it a pity that many people in the West disregard China's economic development models out of hand.

He said people should keep an open mind when trying to find solutions to complicated issues like poverty and rural development.

He said he intends to tell his friends that Danzhai has many creative models which have not been thought about carefully in the US, especially in the way that local culture is protected and promoted.