Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

The violent face-off taking place in June in the Galwan Valley led to fatalities and injuries on both sides. It has altered the era of merely maintaining peace and tranquility on the disputed boundary.

Both sides should have seen this coming - as early as their Doklam standoff in 2017, the tensions were slowly unfolding. Either apathy or ignorance was allowed to thrive. Or perhaps there were only pretensions of trust in their time-tested "managing" capabilities.

It is important to understand how the two countries' methods and mechanism for ensuring peace and tranquility have become dated and ineffective. This novel chapter of ensuring peace and tranquility in India-China border regions began with the 1988 groundbreaking China visit of young Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. His inordinately long handshake with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping finally pulled their equations out of post-1962 war disengagement of disquiet.

This saw these two most populous countries not just open a new era of exploring partnerships but it also set the stage for a complete transformation of their power profile. This has since created new challenges.

The last four decades saw China and India emerge as the world's leading economies. They became internationally engaged societies and influential polities with regional and global responsibilities. China emerged as the world's largest trading nation and second-largest economy. Likewise, India is today the world's fifth-largest economy. After three decades of coalition governments, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's two historic election victories have returned India to its original equilibrium of a "one-party, one-man" style of leadership.

The global vision of the top leaders of India and China - aimed at fast forwarding their respective nation's stature - has transformed India-China ties beyond their historical and bilateral differences. Mutual imaginations of even bilateral issues (like their current stand-offs) are now viewed from the vantage point of their increasing regional and global interactions and initiatives. Their cost-benefit analyses are no longer limited to their ceding or gaining a few miles — however unsettling this calculus might be.

India's engagement with the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue perhaps influences long-drawn China-India negotiations for disengagement in the Galwan Valley far more directly. The prolonged US trade war with China or more recently US-led anti-China tirade over COVID-19 pandemic has surely encouraged India's "boycott China" campaign.

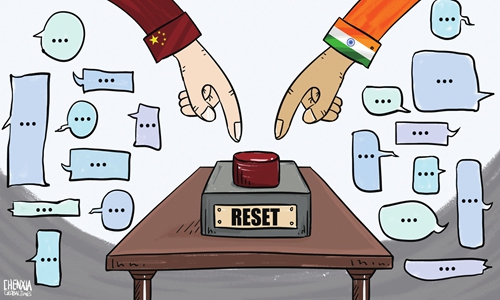

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping have sought to cast a reset of China-India ties through their informal summits. This saw them present new norms like "ensuring that differences are not allowed to become disputes" and "strategic guidance to their respective militaries to strengthen communication in order to build trust and mutual understanding and enhance predictability and effectiveness in the management of border affairs."

However, the implementation of these new templates continues to be based on ineffective and outdated measures and mechanisms.

This is also because on the ground, meanwhile, rising prosperity of China and India has resulted in their forces on border having better infrastructure, better equipment and smarter weapon systems though both sides were able to maintain restraint until the June 15 face-off in the Galwan Valley. But this has made them capable of more rigorous patrols along the border.

As a result, there have been rapid increases in the frequency of ingressions, encounters and fistfights. The increased mobility has resulted in larger numbers of troops, heavier equipment and temporary infrastructure moving forward quickly. This therefore results in ever more intense shows of strength and confidence and leads tempers to run high.

No doubt, both sides have fine-tuned their preventive measures. This includes upgrading the seniority of border meetings from brigade to corps commander. It means supplementing their Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination for Border Affairs with foreign ministers and special representatives videoconferencing. However, these have so far failed to keep them from constantly inching toward perilous brinkmanship.

This repeated slide into brinkmanship calls for an overhaul of all extent methods and mechanism for redressing such eventualities on their disputed boundary. As a first pragmatic step forward, both sides should begin by returning to the April 2020 status quo on all point across the Line of Actual Control.

This may be followed by both sides agreeing to provide advance notice of their patrol plans to the other side. This will prevent soldiers from repeatedly facing each other by surprise. Instead matters can be clarified by using existing communications channels.

The exchange of official maps will give both sides clearer ideas about their claims. It can clear cobwebs of grey areas and minimize surprises about their infrastructure building efforts. Finally, there is a need to analyze India-China ties in their totality and not allow any single issue to monopolize their mutual perceptions and policies.

The author is professor and chair, Center for International Politics, Organization and Disarmament, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn