Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The 3rd China-LAC Foreign Ministers Forum is not due until January of 2021. But in July, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi co-hosted with Mexican Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard, the pro tempore chair of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), a teleconference with a dozen Latin American foreign ministers. They discussed China's cooperation with the region to cope with its current crisis. The takeaway from the meeting was a Chinese commitment to lend up to $1 billion for dealing with the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America.

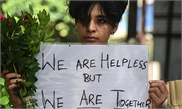

Latin America is a global hot spot for the pandemic. With a mere 8 percent of the world's population, it accounts for one-quarter of the world's fatalities from it, three times what we should expect. According to IMF projections, the region's economy will suffer a contraction of 9.4 percent in 2020, the worst performance of any developing region. The health crisis and the economic recession, in turn, come on top of the social upheavals that rocked many countries in 2019.

Throughout the region, vast sectors of the middle classes, who thought they had escaped the poverty trap, are being pulled back into it. Historically, such massive social upheavals have led to major political realignments. That is what happened in the 1930s and there is no reason to think it will be any different now. The representatives of the so-called blue wave of conservative governments that came to power in this electoral cycle have shown themselves incapable of handling the challenge of the pandemic. Governments that are unable to fulfill their primordial duty, that is, to defend and protect the lives of its citizens, reflect a basic incompetence that deserves that their leaders be relegated to the political wilderness for a long time.

The task for those that would replace them and the task for the new wave of progressive political parties and leaders that will emerge out of the current debacle will be monumental. The enormity of it can be glimpsed from the fact that it will entail not only rebuilding economies and societies that have been shaken to the core. It will not be enough to recreate the many jobs that have been lost, to foster an upsurge of new businesses to replace those that went under, and to redress the many inequities that have blossomed.

What will be needed is a much deeper restructuring of societies caught for far too long in the middle-income trap and in which inequality has been the hallmark. The notion that every so often the region must go through "lost decades" in which, Sisyphus-like, the people endure painstaking social and economic backsliding, with the efforts of many years coming to naught, is unacceptable. Poverty levels are now back to where they were in 2006.

A glimmer of hope is offered by the fact that, in a rather depressing year in which global trade is projected to fall by 30 percent, trade between China and Latin America is starting to pick up. In July 2020, bilateral trade between Chile and China reached $2.26 billion, a 25.3 percent increase over July of 2019, whereas trade with Chile's other main trading partners like the US and Japan fell by 15 percent and 14 percent respectively. From January to July of 2020, Chilean exports to China reached $14.17 billion, a 10 percent increase over the same period in 2019. Something similar is occurring in other countries in South America: In June, Argentine exports to China increased by 50 percent over June of 2019, and by 30 percent in Brazil over June of 2019.

However that may be, a major rethink on how the region approaches its development and its links with the rest of the world is long overdue. This should include, at a minimum, the following:

First, put an end to the current regional fragmentation, in which the rule is basically "everyone for himself." This has been made especially apparent during this pandemic, in which intra-regional coordination has been either nonexistent or woefully inadequate.

Second, embark on a major program to add a measure of value to the commodities and natural resources exported by the region. The condition of "hewers of wood and carriers of water," into which the region seems to have been condemned to, is not conducive to progress and prosperity. It only replicates the eternal cycles of boom and bust of Latin America's 200 years of independent history.

Third, strengthen state capacity and fiscal resources, so that a proper social safety net can be established. This is needed to provide minimum subsistence floor to populations that are sick and tired of going through life as if in a carrousel, so many are the ups and downs.

Fourth, focus on sustainable development across the board, rather than on the old-fashioned and self-defeating type of "slash-and-burn," extractive economic model followed until now.

If there is a silver lining to this once-in-a-century crisis in Latin America, it is that it might trigger at least some of these long overdue changes in a region once again buffeted by tragedy and mayhem.

The author is a research professor at the Pardee School of Global Studies, Boston University, a Wilson Center global fellow, and a senior research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn