IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

WWII still shapes Chinese public consciousness: UK historian

Lessons from history

Rana Mitter, Director of the University of Oxford China Centre Photo: Sun Wei/GT

Editor's Notes: As China is set to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the victory of the world anti-fascist war, Global Times (GT) London-based correspondent Sun Wei spoke with Rana Mitter (Mitter), Director of the University of Oxford China Centre and professor of the history and politics of modern China at Oxford University. Mitter analyzed how the Chinese collective memory of World War II has reshaped China in its following 75-year history until today. He said a great deal of the collective memory of the war in China is not about creating enemies; rather it is about recalling times of collective trauma and healing wounds from the past.

GT: China has undergone earth-shaking changes over the past seven decades. How do you evaluate China's growing strength and role in the international community?

Mitter: Today, China is taking up some of the role that it was seeking in 1945. It is worth remembering that when the Chinese delegation went to San Francisco in April 1945 to debate the new UN Charter, there was a senior CPC figure (Dong Biwu) as well as prominent Nationalist figures such as T. V. Soong. So in some ways, China's growing role in the United Nations and global community today picks up the thread that was started at the end of World War II in 1945.

Today, there are many areas where China is playing a cooperative role in the global community; these including peacekeeping operations (PKO) within the UN, engagement with the Paris Accord on climate change, and discussion of changes to the World Trade Organization. Today, major powers, including the US, China, the EU and others need to spend more time understanding that cooperation does not always mean agreement. I think the international community needs less confrontational rhetoric and all countries should make more genuine attempts to learn from one another.

GT: Many people said the US has launched a "new cold war" on China. Some said it is different from the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. What's your view?

Mitter: I think the Cold War is not the best analogy because during that era, the two sides were quite separate from each other economically. Today, the US and China are still quite dependent on each other in terms of supply chains, financial systems, and technological exchange. This level of interdependence is a reminder that all sides need to take a calm, considered view of how we can keep a stable world at a time of growing economic crisis.

GT: What drives you to write the new book China's Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism? Why and in what way it was a "good" war?Mitter: I had the idea for the book when I was researching my previous book on the history of World War II in China, Forgotten Ally (in the UK, published as China's War with Japan). As I visited China, it seemed to me that memories of the wartime period were everywhere: museums, movies, school textbooks, and social media. Yet very few Westerners seemed to realize that the war continued to play an important role in shaping the way that the Chinese think about themselves today. Also, a great deal of the collective memory of the war in China is not about creating enemies; rather it is about thinking about times of collective trauma in China and healing wounds from the past. So the commemoration of the war in Chongqing's monument today is a reminder that despite political differences, CPC and Nationalist armies came together to oppose the invasion.

The phrase "good war" comes from the US historian Studs Terkel, who wrote a classic book of that title [ "The Good War": An Oral History of World War II] about the US role in World War II, pointing out that many Americans continue to regard it as being a "good" war because it was for a noble cause, despite the horrors suffered during it. I wanted to use the same idea for China; the effects of World War II in China were horrifying but today, many people still perceive it as worthwhile because it led to China defeating the invaders.

GT: Your book Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 attracted significant attention from Western academics and the general public when it was published in 2013. Since then, do you think Western historians have gained a new understanding of China's wartime contributions?

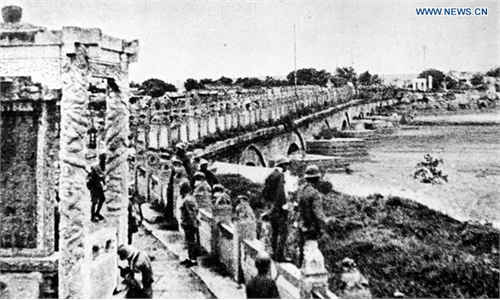

Mitter: I do believe that in recent years, there has been more attention paid to the very important contribution of China to World War II. There has been a greater realization that events in Asia and in China particularly, were central to what became a global war. One example of that is a book published recently, Richard B. Frank's Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War. Frank is a highly-respected American scholar of this period, and his new book on the conflict starts not with Pearl Harbor in 1941 but the Marco Polo Bridge incident in 1937.

Also, if you visit the US National Museum of World War II in New Orleans, you will see a great deal of attention to China's war efforts. And it is also likely that the Imperial War Museum in London will include much more about China's war efforts when its new galleries open. Changing historical interpretations is never a fast process, but I do think the changes in the Western understanding of China's war efforts are real.

Visitors look at photos and documents at the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders. Photo: IC

GT: What is the collective memory of World War II for the Chinese people? How did this collective memory reshape China over the past 75 years? And how does it affect China's handling of catastrophes, difficulties, or external threats like US hegemony?

Mitter: Collective social memory of World War II is a powerful element in the way that China thinks about itself today. This sometimes surprises Westerners, because while countries like Britain, Russia, and the US use analogies and metaphors about the period often, they do not realize that in China, something similar has been happening for many years. A recent example is the campaign against COVID-19, where the phrase renmin zhanzheng [people's war] has been used to describe the fightback. This recalls the language used by Mao Zedong in the 1940s about the resistance war against Japan.

In many other cases, I think the memory of the war is used as a way of contrasting a very different period of time when China was relatively poor and everyday life was a struggle. So for some Chinese, I think that talking about the war is a way of contrasting today's more prosperous lifestyle with the past and reminding people that consumer lifestyles and economic growth cannot be guaranteed. And of course, the war period is also useful for providing a historical contrast with the present day. Right now US-China relations are difficult. So it is worth remembering that the two countries did fight together against dark forces a couple of generations ago.

GT: You once wrote World War II was when the East and the West fought together against the darkest evil forces in history. In the face of today's fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, do you believe Eastern and Western countries can fight the forces threatening human survival and the economy?

Mitter: It is important to remember that science does not have national boundaries. We do not yet know where the vaccine will come from that will control the virus. But we do know that scientists must operate across boundaries and with the freedom and transparency to do their best research, unconstrained by politics. We are proud of the fact that in the UK, some of the best scientists in the world, including Chinese researchers and students, are part of that effort.

GT: Regarding Victory in Europe Day, a US memory lapse of Russia's efforts persists. How do you assess current perceptions?

Mitter: I think that 30 or 40 years ago, during the Cold War, there was insufficient understanding in the West of the decisive contribution of the USSR to winning the war against Hitler.

But these days, I do think that Western historians and the wider public have a much greater understanding of the 20 million or more Soviet soldiers and civilians who died in this cause. Part of the problem has to do with language. For Westerners, it is easier to read accounts of the war using American and British sources, which are familiar and in English. To read Russian and Chinese is harder.