Inspired by inclusive family planning policy, young Chinese expect a fertility-friendly society

Bearing inclusion

Parents holding their children play in the square of a residential community in Nanjing, capital of East China's Jiangsu Province. Photo: VCG

After having two daughters, 43-year-old father Yu Zhongquan in Dalian, Northeast China's Liaoning Province, welcomed his third son in July.

It is just better to have both girls and boys in my family, he told the Global Times, emphasizing that he loves his daughters very much.

"Our family's economic condition can support more children. Although breaking the second-child policy, my wife and I also wanted a third kid, so we have him," Yu said.

However, many Chinese refuse to have more than one kid, due to the heavy burden of raising kids.

Zhang Qian, a 34-year-old mother from Daqing, Northeast China's Heilongjiang Province said, "If I could do it all over again, I would not get married and have a baby."

Checking homework, supervising her six-year-old daughter in practicing dancing skills and reciting ancient poems, Zhang has devoted all her leisure time at night and on weekends to her only kid.

"My husband helped little, holding the stereotype that a wife should take the main responsibility of taking care of kids in a family," Zhang said. "Nobody can manage to persuade me having another kid."

Yu and Zhang are reflections of young Chinese holding different concepts of family planning. However, like Zhang, many people of reproductive age in China are less enthusiastic about starting a family.

According to an article written by the Minister of Civil Affairs Li Jiheng, China's child-bearing age population has low fertility desire, the total birth rate has fallen below the warning line, and population development has entered a critical transition period.

China has actively responded to the disappearing demographic dividend and low fertility rate, partly by putting forth the concept of "inclusiveness" in the family planning policy for the first time, in its most recent Five-Year Plan.

Demographers reached by the Global Times predicted that the inclusive family planning policy would slow down the fertility rate decline to some extent, and the Chinese people are expecting a fertility-friendly society in an all-round way.

The older brother kisses his younger brother on his face in a family of two children in Guiyang, Southwest China's Guizhou Province. Photo: VCG

All in the family

The "inclusiveness" sparked heated discussion and ignited wide curiosity about its implications, especially for groups like unmarried women and same-sex couples, who expect their family planning preferences will be included.

"Tying maternity benefits to marriage certificate is totally unfair and wrong," 36-year-old unmarried woman She Wenqing in Shanghai told the Global Times. "Authorities should support unmarried mothers to encourage more births, rather than frustrating them."

She was extremely disappointed when she was told she can't get the birth allowance afforded to married people, even though she has been paying compulsory maternity insurance for 10 years.

In many areas across China, including Shanghai where She and her boyfriend live, unmarried mothers are not allowed to enjoy some benefits they are entitled to, such as the "80,000 to 200,000 yuan ($12,224-30,560) of birth allowance," She said.

In September 2019, an unmarried mother in Shanghai took a local social security bureau to the court for having her maternity insurance application rejected. Local courts dismissed her complaints in all three trials.

She is among the growing number of unmarried Chinese women demanding equal treatment for out-of-wedlock births, a current grey area of policy.

Yang Ming (pseudonym), 30, came out to his parents as a gay at the age of 20. Yang said that he always wanted to raise a child.

Yang's mother, a traditional woman from Changchun, Northeast China's Jilin Province, struggled to understand and accept her boy's sexual orientation but insisted that he should have his own child. She has even saved up for her son's surrogacy.

Yang told the Global Times that he wishes the fertility desire of minority groups is considered in the coming policy.

"Surrogacy, including registration of hukou for the kid, is a grey area, as long as it is not legislated to guarantee homosexual people's reproductive rights. I want my baby to be admitted and blessed to come to this world," Yang noted.

The demand to allow for a third child is a heated discourse on internet. Yu Zhongquan, who has three children, expects more policies that will support workers' parental priorities.

Yu left home for work at 6am every morning and arrived home around 6pm, leaving most of caring work to his wife and nanny.

Taking care of three children at night drove Yu's family crazy. Yu sometimes leaves office one hour earlier to prepare dinner for his kids. But he has to factor in his boss' mood and leaves apologetically, despite having completed the day's task ahead of schedule.

"I wish the coming policy will give more raising time for families that have three or more children. For example, I am supported by related fertility policy to leave one or two hours earlier for caring my third baby," Yu said, noting "the country would be better off with as many policies as possible reducing the burden of raising children for families who want to have children."

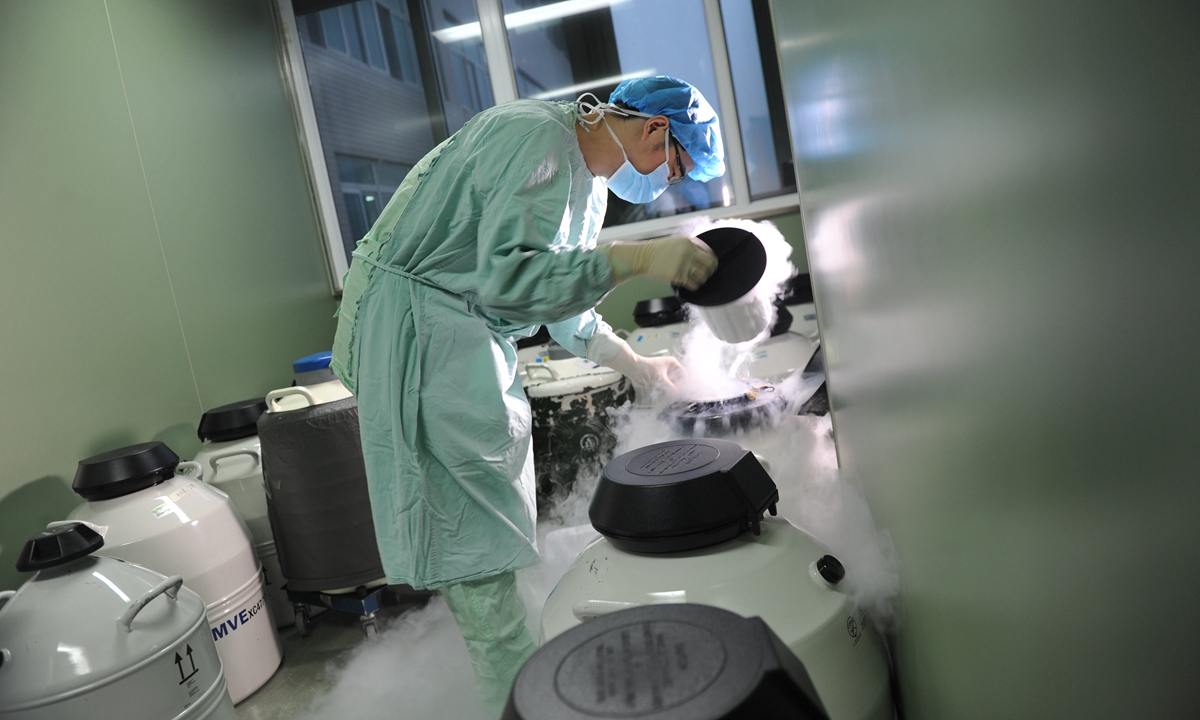

The Reproductive Medicine Center of The West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University is the largest "test-tube baby" center in Southwest China. Photo: VCG

Inclusive policy

Lu Jiehua, professor of sociology at Peking University, said allowing a third child or lifting the family planning policy may be determined by the seventh national population census, due out in the middle of 2021.

To promote demographic adjustment and cope with an aging society, Lu personally recommends China ease the family planning policy as soon as possible and allow families to give birth on their own.

China faces the problem of a demographic dividend loss with its labor force population shrinking in recent years, said demographer Zhou Haiwang, deputy director of Institute of Population and Development under Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. Demographic dividend occurs only when dependency ratio - a ratio of dependent people (not of working age) to working-age people - is below 50 percent, Zhou explained.

China's dependency ratio was 37 percent in 2017, according to a report released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2019. It was predicted to keep rising in the following years and reach around 51 percent in 2032, it said.

Under this circumstance, China's "inclusive" family planning policies are very likely to include lifting the limits on egg freezing, out-of-wedlock birth and how many children a family can have, Zhou estimated, adding that as far as he knows, government departments have been working on investigations and assessments related to these possible policies.

However, Zhai Zhenwu, chairman of the standing council of the China Population Association under the National Health and Family Planning Commission, said fertility policies will hardly be inclusive to unmarried couples and the LGBTQ community, at least until after the next five-year period, according to the current socio-cultural concepts in China. Decrement in the number of births is an inexorable trend, said Zhai.

The number of Chinese women aged between 20 and 35, who are in the period of strong fertility, will drop by 44 percent in 2030, according to the China Fertility Report released by Evergrande Research Institute in 2019.

Zhai said instead of allowing a third or fourth child, it would be good to directly lift the family planning policy and ask the family to decide itself, other than allow a third or fourth child, which could help slightly ease the downward trend in fertility.

The future "signals the country will continue relaxing its family planning policy," Liu Zhijun, a deputy head of the Social Science Experiment Center of Zhejiang University, told the Global Times.

But reforms will likely take time. "Given the continuity of the historical family planning policy and the social mood, it is too early to conclude that within five years, the family planning policy will be abolished and out-of-wedlock births will be included," said Liu, adding that conservative preferences may postpone inclusion of same-sex marriage or surrogacy in the next national policy agenda.

Nearly 1,000 pregnant women practice yoga together at the Hefei Olympic Sports Center. Photo: VCG

Fertility-friendly society

Aside from expectations of an inclusive family planning policy, a growing number of people don't want more kids, citing the economic and physical pressure of raising children and employment discrimination against new working moms.

Official figures show that the number of births in China has been declining for several years in a row. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, 14.65 million Chinese were born in the Chinese mainland in 2019, 580,000 fewer than in 2018; and the birth rate was 10.48 per thousand, 0.46 thousand points lower than in 2018. The birth rate of 2019 was also the lowest since 2000.

Discrimination against women in the workplace for having children always persists, making it difficult for us to enjoy equal promotion opportunities with male colleagues after women get married and have children, Luo Linqi, a 29-year-old woman from Siping, Northeast China's Jilin Province, told the Global Times, noting that she dares not marry and give birth.

Yu Yue, 37, who is a father of a five-year-old girl from Deyang, Southwest China's Sichuan Province, told the Global Times that he won't have another kid no matter how the family planning policy is promoted.

As a working couple, Yu and his wife are not capable of raising more children, without sufficient money and time.

"My mother-in-law, who helped us raise child at her first three years, is 66 years old. My mother's physical condition is not good. No one can help us care for a small baby," Yu said. "The burden of raising a child and caring for our elders is already very heavy for us."

Zhai Zhenwu said that China should continue building a fertility- friendly society to reduce fertility costs and crack down on employment discrimination toward women.

In 2019, the State Council released an official guidance on promoting the development of care services for children under age three.

Authorities can change and improve education and housing policies in line with childbirth encouragement, Zhou Haiwang suggested.

Shanghai, for instance, should change its regulation that people have to pay higher tax on a home larger than 140 square meters than a smaller one, Zhou said. "This is useful in controlling real estate market, but unfriendly to families with more than one child who need a larger space," he said.

Zhai Zhenwu noted a low fertility rate is an inevitable trend of a country's modernization. The state should balance social, economic and cultural policies to create a fertility-friendly environment for people willing to have children.