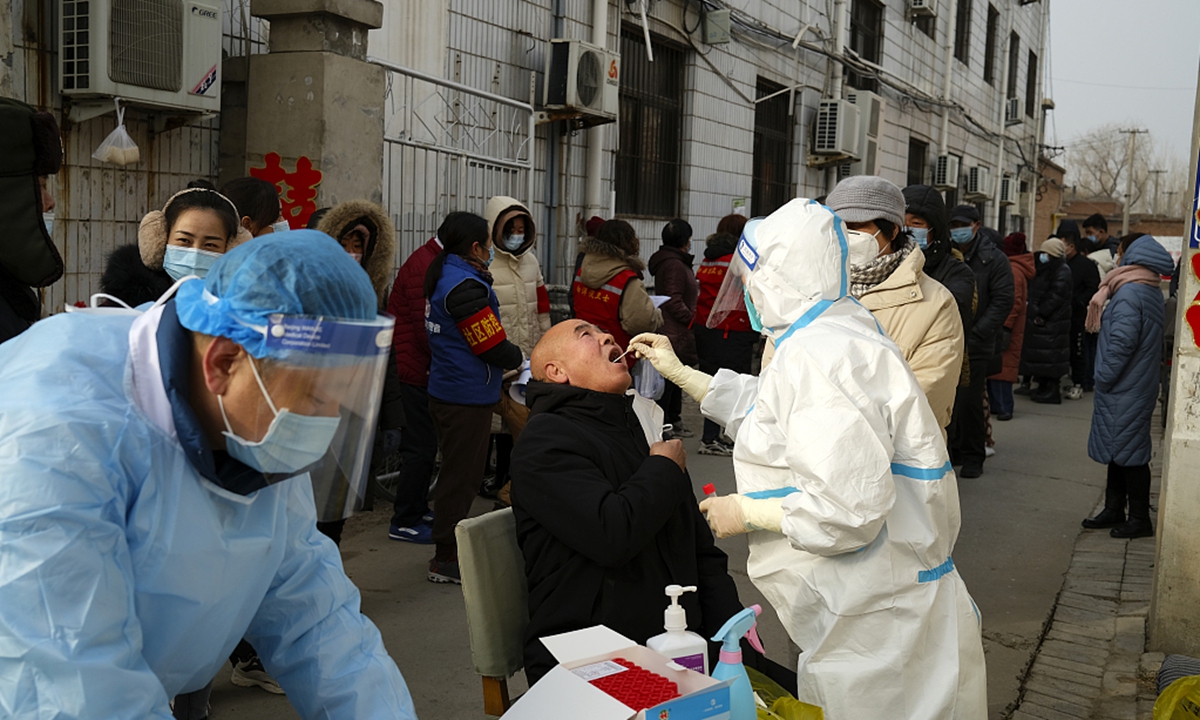

Residents in Xiongan New Area, North China's Hebei Province queue up for nucleic acid tests on January 14. Photo: VCG

North China's Hebei Province reported a death from COVID-19 on Thursday, becoming the country's first coronavirus fatality in about eight months. The case might not be a direct indication that the virus has become more pathogenic but sounds an alarm regarding loopholes in epidemic control in rural areas as most patients in the outbreaks this winter are elderly people from villages with many suffering from chronic diseases.

Although China has invested a huge amount of money in promoting nucleic acid detection capabilities in county-level hospitals, interviews with villagers found that village doctors lack the ability to identify the virus, the awareness to report fever cases and still prefer to choose intravenous therapy that could lead to cross infections instead.

As the Spring Festival travel season nears, many people will return to their hometown, bringing greater challenges to epidemic control in villages. So far, local authorities across the nation have released policies that encourage residents to spend the festival in the places they work. Experts warned special attention should also be paid to the risks in "villages" in urban areas as some migrant workers may not return to their hometown and remain stranded in these places with substandard hygiene conditions.

Cunning virus in villages "Previously, we thought that the countryside was too large and sparsely populated for the virus to spread. But the virus is very 'cunning' as the outbreaks in Hebei and [Northeast China's] Heilongjiang provinces began in the countryside this time," Wu Hao, an expert at the National Health Commission's Disease Prevention and Control Advisory Committee and head of the Fangzhuang community health service center in Beijing, told the Global Times.

The main anti-epidemic task in rural areas in the past was to prevent "imported" cases - blocking roads and keeping outsiders out were enough, he said. However, it turns out that the virus transmission is more complex and covert than once thought.

China's top health authority said local sporadic cases and cluster infections this winter have a long duration and rapid transmission, affecting elderly patients and a high proportion of rural residents. In some places, community transmission and multi-generational transmission have appeared, making the prevention and control situation complicated and grave.

Most of the patients are middle-aged and elderly people from villages. The average age of confirmed cases in Hebei Province is 50 years old, and 30 percent of the cases are over 60. Many of them have been suffering from cerebral and vascular diseases.

Hebei has reported 523 confirmed cases since January 2 and 16 severe cases remain in hospital. From epidemiological investigations into their movements released on the official website of the Hebei Provincial Health Commission, a Global Times reporter found that at least 430 cases live in villages, which account for 84 percent of the total. For example, on Wednesday alone, Hebei reported 81 cases, including 75 in its capital city Shijiazhuang. Of the 75 cases, only four live in the downtown area.

The Global Times has learned that many patients from Xiaoguozhuang, a village under the administration of Shijiazhuang's Gaocheng district and the epicenter of the new outbreak, had visited doctors in village clinics before they were confirmed, which is considered as one of the key reasons why these patients were not detected in the early stages.

"I was given a drip for seven days when I had a cough. The clinic neither gave me a nucleic acid test nor asked me to take one," 56-year-old Fan Li, recalling her memories as she suspects she contracted COVID-19 in late December.

"When we had a fever or cough, we would take pills at home, or turn to village clinics where the only, best treatment was to have an intravenous drip," Fan said.

A doctor from a village in Xingtai, another city close to Shijiazhuang, told the Global Times on the condition of anonymity on Thursday that the reason why many villagers chose to visit his clinics instead of hospitals in the city is because they felt that having a nucleic acid test was a sign of "being sick" and that they will be quarantined immediately.

"Therefore, many village doctors like me would be reluctant to report patients with light symptoms to the city's disease control center or suggest that they get tested," the doctor said. "To be honest, we do not know how to deal with patients with fever, how to protect them and ourselves, and how to find high-risk patients."

Although several provinces such as Anhui, Zhejiang and Jiangxi have implemented restrictive measures to prevent overuse of intravenous therapy, it is still a common practice in villages.

The doctor admitted the reason why they prefer intravenous drip over prescribing drugs is because village doctors can make money that way as the subsidies they receive from the government are small.

"The virus exists in big cities. I live far away from it," this is what most villagers told Li Yuejun, a research fellow from the Institute of Party History and Literature of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, during his visits to villages in Shandong.

"Few villagers have the habit of wearing masks to prevent haze and viruses. Although the relevant knowledge has been popularized through media, my observation in village is that they still do not wear masks," Li said.

Different from downtown communities, villages inside cities are also another potential loophole in anti-epidemic work. Compared with villages in rural areas, it is more difficult to supervise those inside cities as residents living there flow in and out frequently, Wu said.

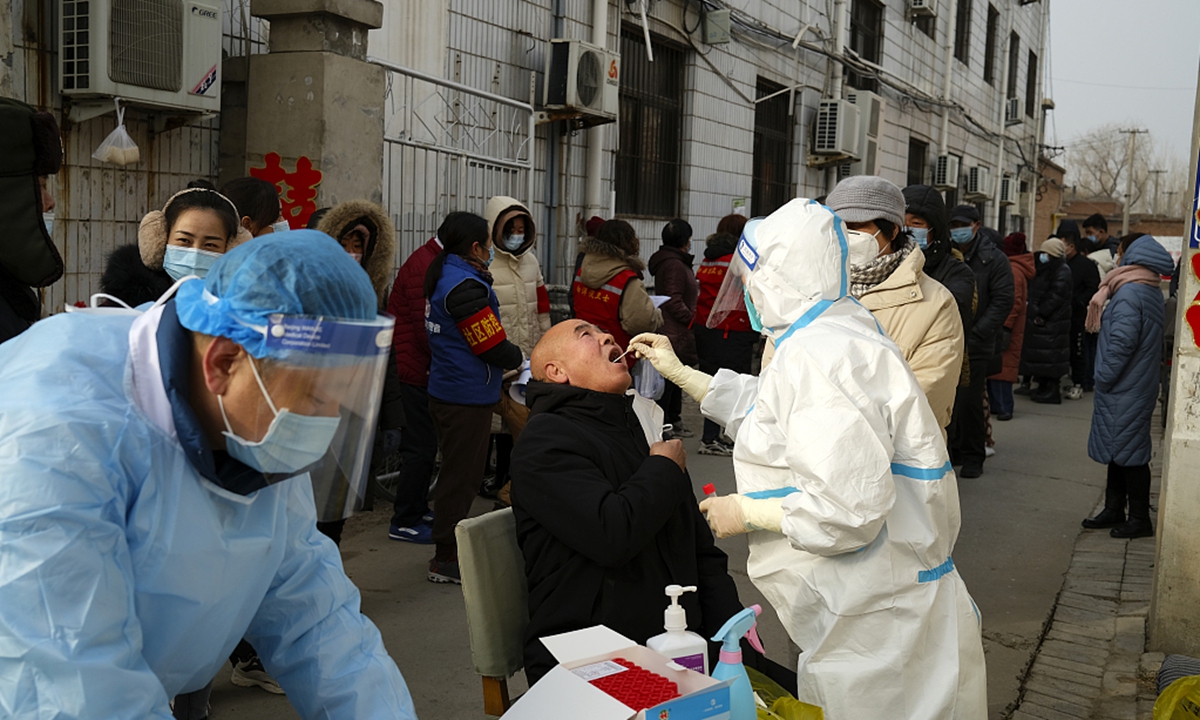

Villagers took a designated bus to quarantine centers in Shijiazhuang, N China's Hebei Province, on January 11. Photo: VCG

Joining the battleSince Monday, after clustered infections in Xiaoguozhuang village turned Gaocheng district into a high-risk zone, authorities in Shijiazhuang started moving 20,000 villagers from 12 villages to other townships for quarantine.

The provincial capital also began building 3,000 makeshift housing units on Wednesday for quarantining patients.

To cope with the new outbreaks, loudspeakers started announcing messages, long banners alerting residents were hung on walls, mechanical diggers and metal plate serving as road barriers were set up to examine vehicles and visitors. Some villages are coming up with new ideas in joining the battle against the recent flare up.

Many cities have announced to cancel group gatherings during Spring Festival holiday. Media reports showed an increasing number of village officials are advocating locals to delay or cancel ceremonies such as weddings, and holding funerals in a simple manner.

Strict monitoring and inspections on people returning home should be implemented to curb the COVID-19 spread in villages, but they are also a valuable source for local officials in promulgating correct knowledge to elderly people, Wu said.