In the past, shareholder votes on the environment were rare and easily dismissed. Things could look different in the annual meeting season starting March, when companies are set to face the most investor resolutions concerning climate change in recent years.

In the US, shareholders have filed 79 climate-related resolutions so far, compared with 72 for all of 2020, according to data compiled by the Sustainable Investments Institute and shared with Reuters. It is estimated that the count could reach 90 in 2021.

Topics to be voted on at annual general meetings (AGMs) include calls for emission limits, pollution reports and "climate audits" that show the financial impact of climate change on their businesses.

"Net-zero targets for 2050 without a credible plan including short-term targets is greenwashing, and shareholders must hold them to account," said billionaire British hedge fund manager Chris Hohn, who is pushing companies worldwide to hold a recurrent shareholder vote on their climate plans.

Royal Dutch Shell said on February 11 it would become the first oil and gas giant to offer such a vote, following similar announcements from Spanish airports operator Aena, UK consumer goods company Unilever and US rating agency Moody's. While most resolutions are nonbinding, they often spur changes with even greater than 30 percent or more support as executives look to satisfy as many investors as possible.

Companies warm the worldWhile far more companies are issuing net-zero targets for 2050, in line with goals set out in the 2015 Paris climate accord, few have published interim targets. A study from sustainability consultancy South Pole showed just 10 percent of 120 firms it polled, from varied sectors, had done so.

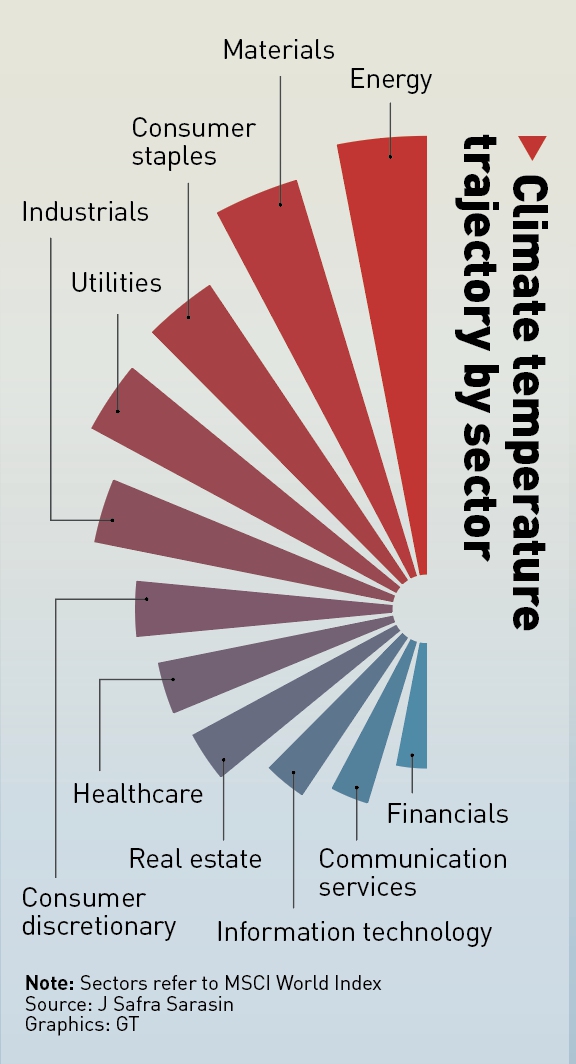

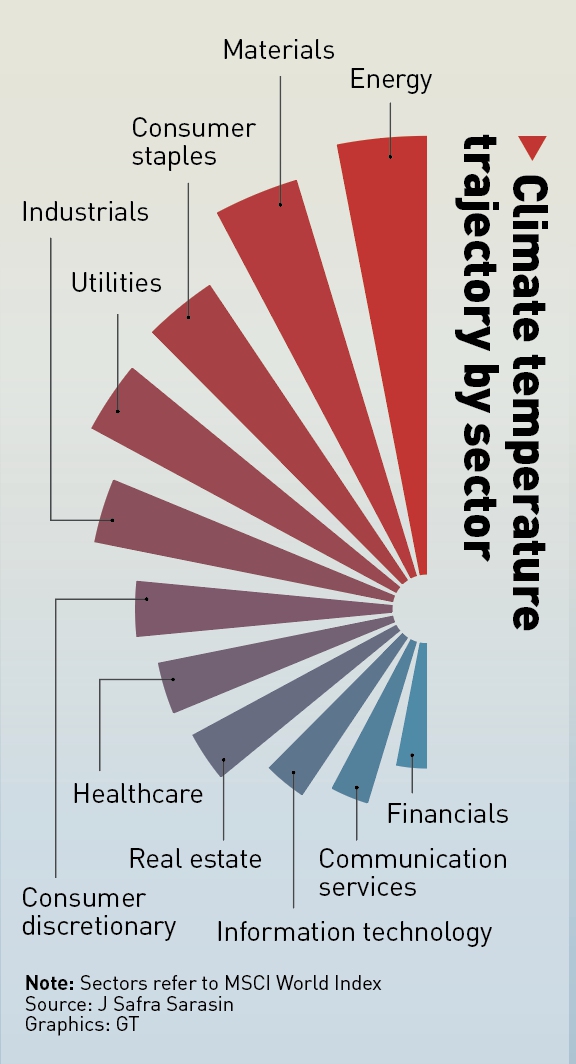

Data analysis from Swiss bank J Safra Sarasin, shared with Reuters, shows the scale of the collective challenge.

Sarasin studied the emissions of the roughly 1,500 firms in the MSCI World Index, a broad proxy for the world's listed companies. It calculated that if companies globally did not curb their emission rates, they would raise global temperatures by more than 3 C by 2050. That is well short of the Paris accord goal of limiting warming to "well below" 2 C, preferably 1.5 C.

On an industry level, there are large differences, the study found: If every company emitted at the same level as the energy sector, for example, the temperature rise would be 5.8 C, with the materials sector - including metals and mining - on course for 5.5 C and consumer staples - including food and drink at -4.7C. The calculations are mostly based on companies' reported emissions levels in 2019, the latest full year analyzed, and cover Scope 1 and 2 emissions - those caused directly by a company, plus the production of the electricity it consumes.

Tailwind on climateSectors with high carbon emissions are likely to face the most investor pressure for clarity. In January, ExxonMobil - long an energy industry laggard in setting climate goals - disclosed its Scope 3 emissions, those connected to use of its products.

This prompted the California Public Employees' Retirement System (Calpers) to withdraw a shareholder resolution seeking the information.

However, Exxon has asked the US Securities and Exchange Commission for permission to skip votes on four other shareholder proposals, three related to climate matters, according to filings to the SEC, citing reasons including "substantially implemented" reforms. An Exxon spokesman said it had ongoing discussions with its stakeholders, which led to the emissions disclosure. He declined to comment on the requests to skip votes, as did the SEC, which had not yet ruled on Exxon's requests as of late Tuesday.

A group of climate activists that have been cycling from the North of the country in stages to draw attention to the climate case are arriving at the Court of Justice on the day that the climate lawsuit against Shell starts in The Hague, the Netherlands, on December 1, 2020. Photo: AFP

Step in right direction Given the influence of large shareholders, activists are hoping for more from BlackRock, the world's biggest investor with $8.7 trillion under management, which has promised a tougher approach to climate issues.

On February 17, BlackRock called for boards to devise a climate plan, release emission data and make robust short-term reduction targets, or risk seeing directors voted down at the AGM. It backed a resolution at Procter & Gamble's AGM, unusually held in October, asking the company to report on efforts to eliminate deforestation in its supply chains, helping it pass with 68 percent support.

Europe's biggest asset manager, Amundi, said on February 18 it, too, would back more resolutions.

Vanguard, the world's second-biggest investor with $7.1 trillion under management, seemed less certain, though. Lisa Harlow, Vanguard's stewardship leader for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, termed it as "really difficult to say" whether its support for climate resolutions in 2021 would be higher than its traditional rate of backing one in ten.

There will be fightsBritain's Hohn, founder of $30 billion hedge fund TCI, aims to establish a regular mechanism to judge climate progress via annual shareholder votes.

In a "Say on Climate" resolution, investors ask a company to provide a detailed net zero plan, including short-term targets, and put it to an annual nonbinding vote.