Dearth of blue-collar workers in China severe after the Spring Festival

Labor shortage no threat to economic rebound

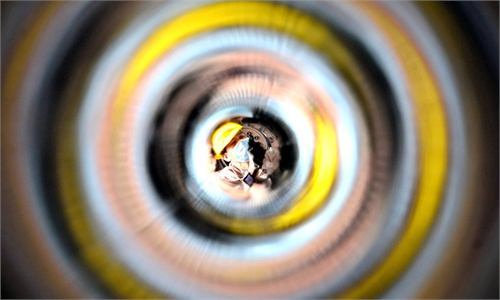

Workers who chose to stay at their factory in Shaoxing, East China's Zhejiang Province during the Spring Festival holidays decorate their dormitories on January 28. Photo: Yang Hui/GT

As the world's factory stages a strong economic recovery in the post-COVID era, manufacturers throughout China are grappling with a worsening shortage of blue-collar workers after the Spring Festival holiday.

But an expert said that the shortage poses no threat to the nation's sound economic recovery as it's a longstanding problem, and major companies have stepped up efforts to solve it by introducing automation.

A video reflecting how severe the shortage is went viral on Chinese social media. In the video, the owners of garment factories stood in a line of about 3 kilometers in an alley in Guangzhou, South China's Guangdong Province.

Holding their ready-made clothes and advertising board that clearly showed job posts and salary levels, the owners hoped that pass-by job applicants would stop, look and perhaps ask for a job.

"We used to be the ones who picked the workers. Now the workers pick the bosses," Li Ailian, owner of a garment factory, said in the video.

The Global Times heard similar comments from managers at other manufacturers. "The labor shortage has been severe after the Spring Festival holiday, as workers went back to their hometowns before the festival, but many have not come back yet," said Hong Shibin, deputy executive director of the marketing committee of the China Household Electrical Appliances Association.

Taking the home appliance industry as an example, Hong said that skilled technicians are badly in need after the Spring Festival, when the demand for home appliances, such as air conditioners, will soon reach the peak selling season.

Hong, who owns a home appliance company in Guangdong Province, told the Global Times that his plant is short of one-third of the necessary workers, or about 100 people, leaving the risk of back orders.

"We are now encouraging all employees to recommend applicants to work for us. Anyone who recommends a successful candidate will be given a reward of 300-500 yuan," or ($46-78), Hong said, adding that the factory also gives incentives to long-serving employees.

John Ng, the factory manager of Maisto, a model toy maker in Dongguan, Guangdong, told the Global Times on Monday that the company has also experienced a labor shortage after the Spring Festival. As the company adjusted production plans before the holidays, the impact is limited.

"We produced the parts that could be pre-made before the holidays to ease production pressure afterwards," Ng said, and the company is also working with recruiters to hire people from less developed areas.

However, he said that there is no instant solution for the labor shortage. In the long run, the company will improve the management structure to increase working efficiency.

Labor demand by manufacturers during this Spring Festival holiday period rose 115.2 percent compared with 2020, and it was 64.9 percent higher than in 2019, job-hunting platform Zhilian Zhaopin told the Global Times on Monday.

"In previous years, workers came back to factories after the two-weeks Spring Festival. But in 2021, many migrant workers choose to stay put during the holiday, while also driving further labor shortage in the manufacturing sector," the company said.

In China, labor shortage first emerged in 2003 and then expanded from southeastern coastal areas to the entire nation, according to Li Chang'an, a professor at the department of public economics at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing.

"The main reason is the shift in China's demographic structure with a declining labor force proportion," he told the Global Times.

Official data show that the number of working-age people in China has decreased since 2012. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security announced on Friday that China's working-age population may drop by 35 million from 2021-2025, entering a moderately aging society.

In addition, working in cosmopolitan cities has become less attractive to rural workers, Li Chang'an noted. "High living costs in big cities have diminished their interest in working in cities, while the country's rural revitalization plan has pulled some people back to the countryside."

For Hong, the reason for the dearth of blue-collar workers is that many people who were born in 1990 and thereafter want more than just money. "Companies should also have canteens, libraries, fitness rooms and small cinemas, as well as flexible working hours."

With the flourishing development of the online economy, many young people in China have shifted to delivering parcels or food, or working for ride-hailing companies. According to a report by China News Week, nearly 30 percent of the 2 million new deliverymen working for online take-out platforms Meituan Dianping and Eleme.com used to be manufacturing workers.

To solve labor shortages, Li Chang'an suggested companies develop vocational training for migrant workers and resort to more automation. "Prolonging work age of 60 years old for most men could also be a choice."

Increasing labor costs would affect China's advantage in manufacturing, he admitted, but won't weaken its overall comparative advantages. Instead, it may push forward the country's industrial upgrading and transformation.