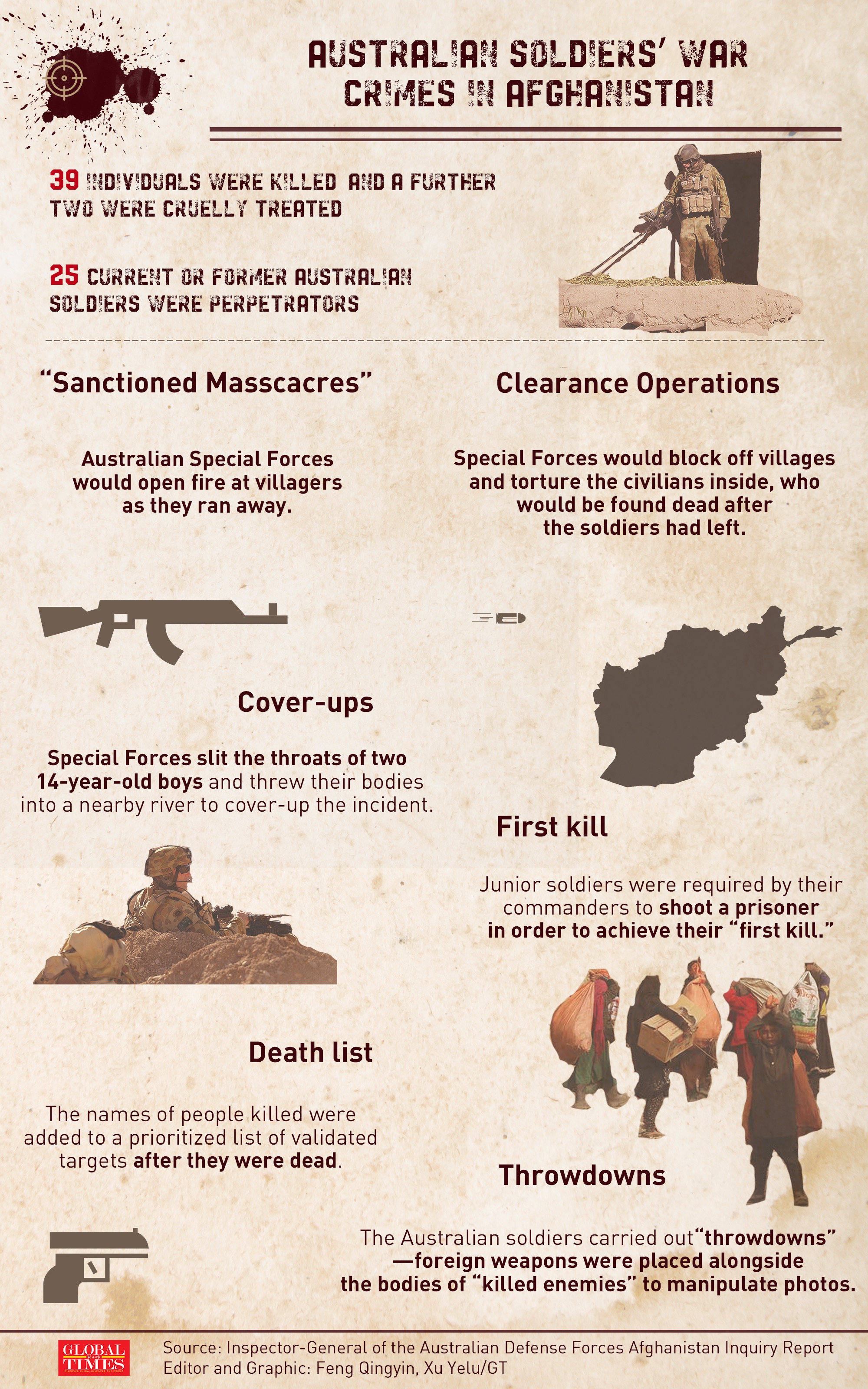

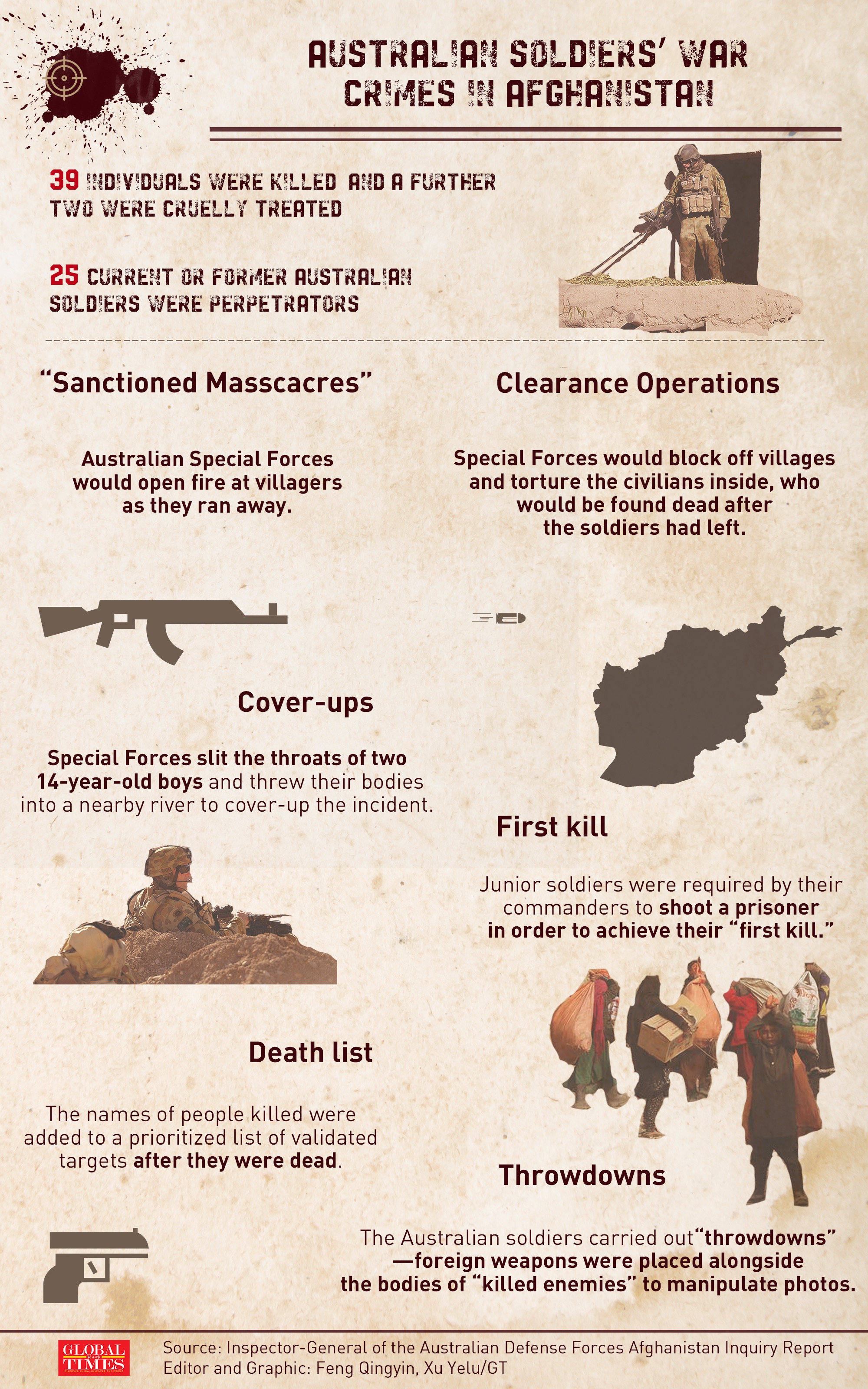

Australian soldiers' war crimes in Afghanistan. Infographic: GT

An end day was put to the longest war so far as Australia is to pull out all its remaining troops in Afghanistan following accusations of war crimes and the U.S. decision of withdrawal. But harm is done, and the scars and wounds will be left open should history was misrepresented, truth veiled again and justice remains undone.

The "good war Afghanistan" is just the opposite of its literal sense. In November 2020, the Brereton Report was released after a four-year inquiry into misconduct of the Australian forces in Afghanistan. What the detailed report reveals is, as some people call it, just "a tip of the iceberg" of the atrocities committed by the Australian Defence Force (ADF).

The Report "discloses allegations of 39 unlawful killings by or involving ADF members, and separate allegations that ADF members cruelly treated persons under control." Frankly enough, the Report admits that none of these crimes was committed during the heat of battle. The victims were noncombatants or no longer combatants. Still, some perpetrators are serving.

The Report also finds that junior soldiers was coerced to take lesson 101 of "blooding" by killing a prisoner. This is how it works: a patrol commander would take a person under control and a junior member would then be directed to kill him. Other soldiers would then feign a combat setting and create a "cover story" for operational reporting and to deflect scrutiny. No one is allowed to say anything. The code of silence ensures a smooth chain of demand and deliberate normalization of cold-blood murder.

In fact, independent reporting and investigation has been going on, trying to hold people involved accountable. Photos taken in 2009 show Australian troops drinking beer out of a prosthetic leg of a dead enemy in Uruzgan province, where a Australia military base is located. In 2015, troops stationed in Afghanistan made confessions of misconducts or even explicit war crimes to a researcher, who was supposed to study the Australian military culture. The author, Dr Samantha Crompvoets, was told that members of the Special Air Service Regiment, an elite group in the ADF, cut the throats of two 14-year-old Afghan boys before dumping their bodies in a river because they thought the boys were Taliban sympathizers. Defence documents leaked to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2017 give a full account of the killing of civilians and impunity that ensued.

The official reactions by the Australian government keep letting the world down. Red flags and warning signs of the troops were neglected, which could have prevented the crimes should actions had been taken in the first place. The reluctance to face facts, the lack of responsibility and failure to reform the military culture seem to have forged the dead cycle of misconduct,disclosure and apologies. Real actions are yet absent. Charges against commandos involved were brought and dropped for reasons unknown. Complaints from locals and human rights groups were dismissed as "Taliban propaganda" or attempts to obtain compensation. The Brereton Report itself determined that responsibility for the alleged crimes "does not extend to higher headquarters."

By the same standard the Australian politicians have been accusing other countries, the murder of civilians and other violent crimes in Afghanistan should constitute crimes against humanity, and the criminals should pay their price in accordance with the Geneva Conventions and related protocols. When the domestic trial model in Australia cannot work efficiently and sufficiently, the International Criminal Court may be a proper place to adjudicate on the cases of grave human rights violations. People cannot be killed and forgotten. Afghan people deserve to hear confession and penitence.

The Afghan people have called for justice. They are still trying hard. The Afghan government strongly condemns the violations and considers them indefensible. The Afghan Foreign Ministry stated that it was working with the Australian government to investigate the wrongdoing of Australian soldiers in Afghanistan to ensure the perpetrators were identified and brought to justice. An editorial in Afghanistan Times stated that the best that Canberra can do is to investigate war crimes in the most transparent manner.

Human rights experts are calling on the Australian government to bring in people directly concerned. Hadi Marifat, executive director of the Afghanistan Human Rights and Democracy Organization, suggested including victims in criminal investigation is the first step toward justice. Shaharzad Akbar, head of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, pointed out witnesses from Afghan forces should be involved to help with prosecutions of Australian soldiers.

But such candidness may be too much to ask. Australia was already offended and flipped out by a computer graphic depicting murders of an Afghan kid, even calling it a "fake photo". Defending human rights in a serious manner, it turns out, is far more difficult than just waving the banner. Admitting human rights problems head on requires extraordinary courage; addressing mistakes, especially those made by one's own, takes many more times of efforts. As the time for "pack-up and go" is drawing close, Australian and other Western troops should urgently consider what they wish to leave behind in Afghanistan. The options are on the table, peace and stability following an orderly and responsible departure, or persisting intrusion and violations of rights.