COMMENTS / EXPERT ASSESSMENT

Simply throwing money may not fulfill Europe's semiconductor dreams

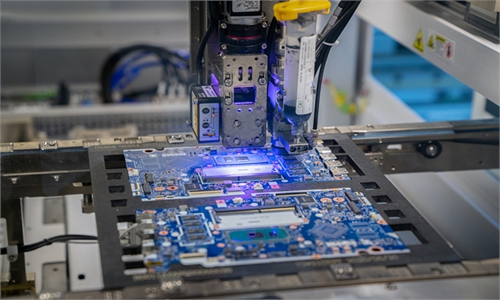

Photo:VCG

Europe's calling to achieve self-reliance on semiconductor production has been gathering momentum recently. The European Commission is reportedly planning to roll out a strategy to support the development of its microchip industry in the short term and EU officials have been holding talks with giants such as TSMC, Samsung and Intel to lure them with high subsidies to build factories in Europe.

Europe's microchip industry did have a glorious history, with its production accounting for 40 percent of global capacity in the early 1990s. However, due to the decline of local electronics, companies like Nokia and Ericsson, as well as the shrinking demand from Europe's electronics industry, European chip makers started to shift manufacturing to the Asia-Pacific region and to focus on development of chip design and technology. The EU now has just 10 percent of global semiconductor production capacity, far behind the US and Asian economies.

As the COVID-19 pandemic shattered global industrial supply chains and triggered a worldwide chip shortage, European auto industries have been taking hard hit, putting more pressure on this pillar of the European economy.

The EU decided to distribute 20 percent of its pandemic recovery fund into chip manufacturing and other digital priorities, showing a consensus among its members to shore up its microchip sector. Also, it has vowed to increase production capacity to at least 20 percent of the world's chips by 2030.

It is true that the EU, to a certain degree, has fallen into a weak position in economic and geopolitical issues due to the lack of domestic chip manufacturing capacity, while production and technology have increasingly become a standard configuration for major powers in the world.

The bloc now regards control of industrial supply chains, including the semiconductors, as an important feature of its strategic independence and digital sovereignty but there is still a huge gap between the chip self-reliance and the reality of this industry.

For starters, achieving complete self-reliance on chip manufacturing itself is not a realistic goal. Against the backdrop of globalization, countries and companies have been developing their most competitive businesses in chip supply chain according to comparative advantages. So far, there is no country or region which can manage to cover the whole industrial supply chain. Trying to achieve a closed-loop development or absolute self-reliance on the chip industry is not only technically difficult but it also demands huge economic and social costs.

The development of semiconductor industry is a long-term project and large-scale expansion of capacity is almost impossible to accomplish in the short term. Building a microchip factory is a systematic project, requiring adequate preparation in talent, land, supporting infrastructure, ensured supply of raw material and energy among other factors, to build an entity linking both ends of the supply chain, rather than simply setting up several production lines or assigning pieces of lands.

Moreover, the EU needs to foster an environment which is conducive to the growth of chip manufacturing. The offshoring of Europe's chip production followed the overall manufacturing shifting trend of global consumer electronics to Asia-Pacific region. It is a normal practice for companies to set up manufacturing near the markets which demand intermediate or end products. The essential task for Europe is to foster demand if it intends to seize a larger proportion of the global chip manufacturing capacity. Products from global giants produced in Europe will ultimately serve the interest of their parent company instead of local manufacturers.

As for the semiconductor sector, Europe's attempt to turn cash into real industrial capacity is more likely to end up as nothing but a dream. Raising investment is only one of the prerequisites to foster a competitive semiconductor industry. It requires more sustained and long-term efforts.

The article was compiled based on a commentary written by Dong Yifan, a research fellow with the Institute of European Studies at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn