Is China's birth rate low enough to cause population crisis?

Chinese demographers warn critical challenge, but differ on policies

Children play in an adventure playground at a tourist attraction in Nanning, South China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, May 1, 2021. Saturday marks the first day of China's five-day May Day holiday. Photo: Xinhua

Now that the 30-page seventh national population census communiqué which contains thousands of figures has been released, what is behind the data and what does it reveal about the true picture of China's demographic changes? How strong should China's population policy adjustment be to cope with the trend? How low is Chinese couple's willingness to have more children, could it be low enough to result in a population crisis a few years from now? And should China reward couples with 1 million yuan ($155,400) for every child they have, as advised by some demographers?

Chinese demographers have been vigorously debating these questions since Tuesday, but they differ on the interpretation of China's actual fertility rate, the severity of the population situation as well as the incentive policies to encourage more births.

Demographers agreed that China's population has come to a critical turning point as the country's population ages rapidly while the overall growth rate slows, and that the country needs to speed up the removal of the family planning policy, and draft new retirement plans and social policies to lower the cost of raising children.

Some demographers who seemed to be deeply troubled by those figures calculated their own figures which point to a lower fertility rate, predicting an alarmingly worrying future scenario for China's population development to warn that China may become the country with the world's lowest fertility rate. Based on these predictions, they advise the country to spend up to 10 percent of its GDP to reward newborns, by giving bonus up to 1 million yuan to each child one couple has.

But other demographers said China is so far still the world's most populous country with abundant labor resources and promising economic development prospects. All these concerns, no matter too much or not, could be eased or even dispelled through active policies and efforts by society that are adapted to China's current stage of development.

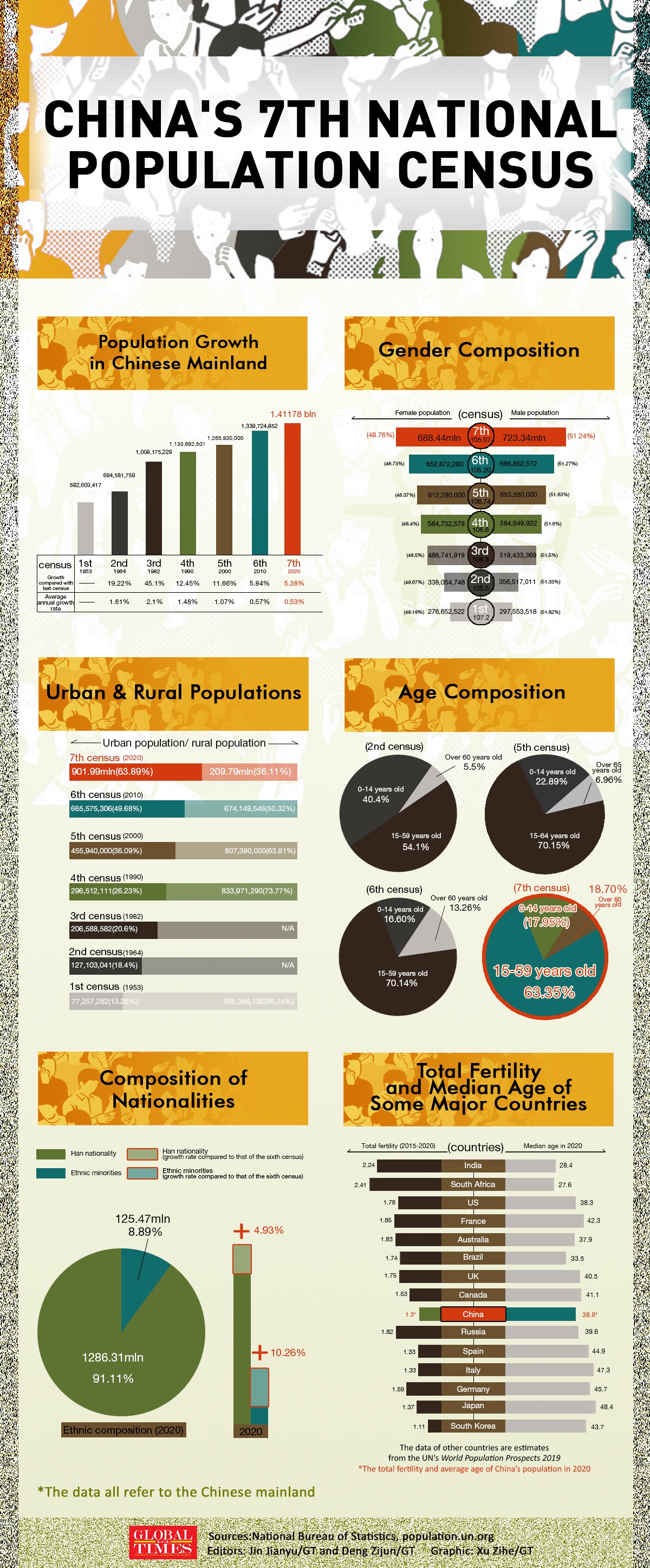

China's 7th National Population Census Infographic: Xu Zihe/GT

Fertility rate much lower?

The number of newborns in China in 2020 was 12 million, down from 14.65 million in 2019, and China's fertility rate of women of childbearing age was 1.3, a relatively low level, according to the census, which was released by the National Bureau of Statistics on Tuesday.

He Yafu, an independent demographer, told the Global Times on Tuesday that the fertility rate of 1.3 contains the disappearing effect of the second-child policy China introduced in 2016, and leaving out this bump, the fertility rate could only stand at around 1.1.

Echoing with He, Liang Jianzhang, an economics professor at Peking University, wrote in an article that China's fertility rate will continue to drop in the coming years, and may become the world's lowest.

"According to the existing data, in the next 10 years, the number of women aged 22 to 35, which is the childbearing period, will drop by more than 30 percent compared with the present data. Without strong policy intervention, China's newborn population is likely to fall below 10 million in the next few years, and its fertility rate will be lower than Japan's, perhaps the lowest in the world," Liang predicted.

According to the World Bank, the birth rate of South Korea, Japan, US and the EU in 2018 was 0.98, 1.42, 1.73, and 1.6 respectively.

He Yafu said that the effect of the second-child policy may fade in 2022 when the number of first children born is expected to outnumber the second, and that is when China's population will start to decline.

Huang Wenzheng, a demography expert and senior researcher from the Center for China and Globalization, expressed his concerns on how fast the rate of population growth is decreasing, and if the trend continues, it will be like the population is jumping off a cliff, he said.

The expert noted that the two-child policy has helped to increase the birth rate and babies, however the number of newborns was lower than previous estimates.

However, some demographers argue that although China faces great pressure on the birth rate and demographic changes, China's fertility rate would not be the world's lowest.

Du Peng, a professor at the School of Sociology and Population Studies at the Renmin University of China, told the Global Times that we could calculate the proportion of first and second children in the total number of newborns, but we cannot split up first child and second child in terms of fertility rate.

The fertility rate of women of childbearing age is produced after calculating the number of births for women aged between 18 and 49, Du said.

Song Jian, a demographer from the Center for Population and Development Studies of the Renmin University of China, told the Global Times the fertility rate of 1.3 reflects the fertility rate of a specific period in China, which may be affected by several factors, including the impact of COVID-19 in 2020.

What is needed to assess whether a country has fallen into the trap of low fertility is replacement level fertility, which refers to the average number of children born per woman in her lifetime. That figure takes a long time to track and calculate, Song said.

But experts agreed that the fertility rate which has been dropping for several years still looks grim, and China needs to figure out ways to encourage couples to have more children.

Want more babies?

China's population structure has been changing since the fifth population census in 2000, and the country needs comprehensive social policies to cope with the new population development paths, Lu Jiehua, a professor of demographics at Peking University, told the Global Times.

"Among those policies, further improving or lifting the family planning policy is at the top of the policy list," Lu said.

Du also believes that China should lift the family planning policy so people can choose themselves whether to have more babies.

But some argued that even if without the policy restrictions, people who do not want to have more children will not choose to have more, even with incentives.

On Weibo, several hashtags relating to choices on whether to have second child have attracted tens of millions of views, with many net users worried about the cost of having more children, believing that only the wealthy can afford it.

Ning Jizhe, head of the NBS, said at a press conference on Tuesday that according to their survey, women of child-bearing age in China are willing to have an average of 1.8 children and "if we can doing a good job on supporting measures, the potential fertility will be released."

A national survey recently completed by Song Jian, echoed Ning's remarks.

Song told the Global Times that they found most Chinese couples surveyed said they are willing to have a second child, but not all of them put this willingness into action.

Chinese people used to think that it an ideal family pattern was a boy and a girl in a family. Knowing what hinders people from having children and adjusting favorable policies in accordance with people's concerns to make a fertility-friendly environment would be crucial to promoting the fertility rate in China, Song said.

Cash bonus needed?

Apart from lifting the family planning policy, how to lower the cost of raising children is the most important question for couples as revealed by many netizens' comments and surveys.

But Chinese demographers differed on how strong the policies in lowering the cost should be, more specifically, could China simply give each newborn cash bonus? How big should the bonus be?

How to encourage fertility should be a key topic for society and this is an all-around program that would include reforms on social policies, Liang said, who suggested China spend 2-10 percent of its GDP on the program. "China's GDP in 2020 was 100 trillion yuan and 10 percent means 10 trillion yuan. If we say that China now needs to have 10 million children additionally every year, it means every child would get 1 million yuan - the subsidy can be in cash, tax reductions or housing allowances," Liang said.

He suggested reforming the education system, adjusting the current land policies to increase land supply and to decrease housing prices as well as offering housing subsidies to families with children, and promoting gender equality to build a female-friendly society. Liang also suggested promoting flexible working models, completing social welfare for single parent families and legalizing assisted reproduction.

However, Du believes that the money would be better spent collectively to build more affordable kindergartens and a fairer education system for society in order to get a sustainable and stable fertility rate.