Will Japan stop doing evil on nuclear wastewater issue? International community is watching

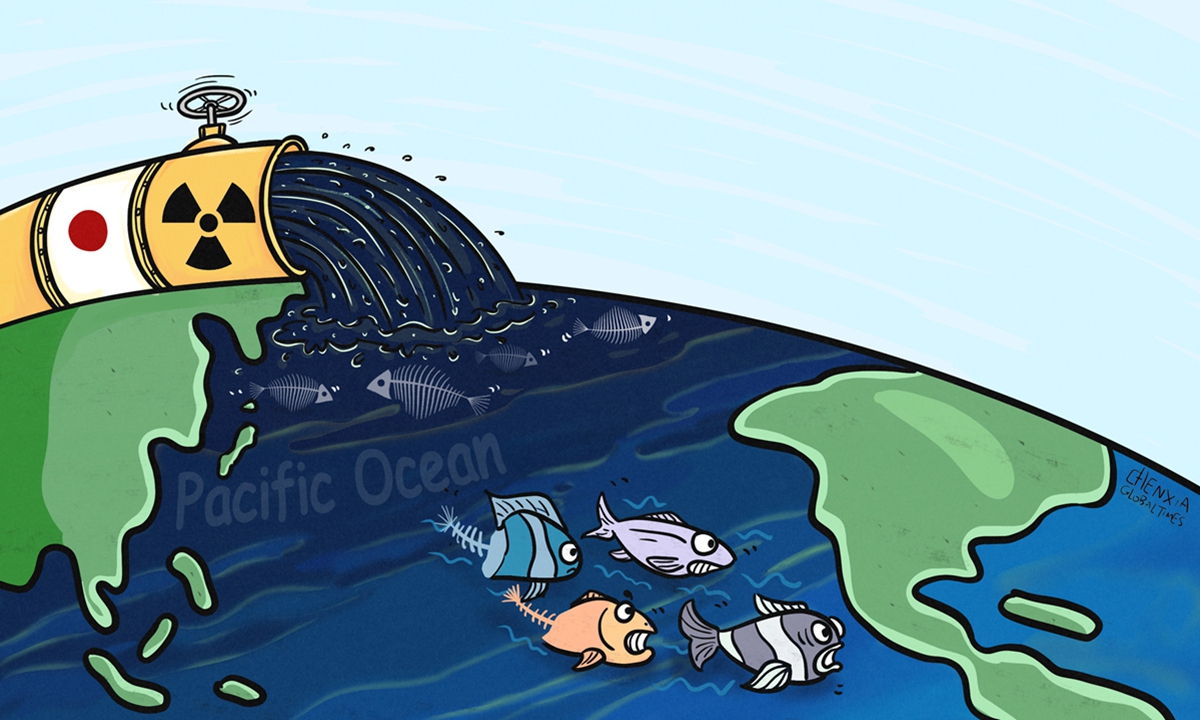

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Editor's Note:

Japan asked the city of Hong Kong and Macau in early June to lift food import ban on seafood and agricultural products from the areas around the Fukushima nuclear plant, trying to address regional concerns over its plan to release more than one million tons of "treated" wastewater from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean. In fact, Japan's decision has triggered strong criticism both inside the country and from its neighboring countries and regions, and South Korean fisheries associations filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government at a local court on May 13. Is discharging the nuclear wastewater Japan's last and only way out? How can the international community resist Japan's decision? Global Times (GT) reporter Li Qingqing talked to Shaun Burnie (Burnie), senior nuclear specialist of Greenpeace East Asia, about these issues.

GT: Greenpeace published an article at the end of April saying that the nuclear wastewater generated since the Fukushima incident had reached over 1 million metric tonnes until March, among it 778,000 metric tonnes is yet to undergo secondary ALPS processing. Nor is there a clear schedule for when the secondary processing can proceed. How will Japan and the international community react if the water is still not properly treated when the 2022 "deadline" comes?

Burnie: The deadline is artificial as there is sufficient storage space on the Fukushima Daiichi site for additional tanks - and there is sufficient storage space outside the facility in Okuma and Futaba districts.

Although no detailed plans have been released by the Japanese government or TEPCO our analysis is that the deadline when discharges are scheduled to begin - which I think will be in 2023 - does not apply to the water that still needs secondary processing.

If TEPCO were to proceed with discharging only the water that can be diluted and at the maximum radiation limit for tritium - it would be just under 30,000 cubic meters per year - with just 500,000 cubic meters of this water it will be between 10 and 16 years to discharge. During this period they would continue to operate a secondary ALPS for the remaining water (778,000).

It's important for all concerned with the discharge plan to seek full disclosure of Japanese government plans, including the operation of ALPS and the radiological content of the tank water; and to call on the Japanese government to abandon plans for discharge and to develop long term storage and processing.

GT: Japan's decision has triggered serious protests from the international community, especially neighboring countries. South Korean fisheries associations filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government at a local court on May 13. How much impact will similar measures impact Japan's decisions?

Burnie: Citizens and the governments that represent them have the right to defend the health, environment and economic well being - in that sense filing court action to address the consequences if Japan were to proceed with discharges is important. What the legal consequences will be very much depends on each case, the evidence presented and the judgment of the court. The Japanese government has been successfully challenged in court in Japan over nuclear operations and it is clear that it has an effect.

GT: Pacific Islands Forum Secretary General Henry Puna on Saturday called for a frank discussion ahead of a meeting with the head of the IAEA after the organization said Japan's dumping plan was technically feasible. How do you evaluate IAEA's response?

Burnie: The IAEA is not a neutral actor in this issue - it strongly supports Japan's nuclear program, and is seeking to support efforts for Japan to continue nuclear reactor operation - as it does with all countries worldwide operating nuclear reactors. The IAEA will play an important role in trying to explain that there are no hazards from the radioactive water to be discharged by Japan. Greenpeace does not support the IAEA in its support for nuclear power and disagrees with its assessment that there are no hazards from dumping nuclear waste into the sea.

GT: As far as you know, is there still room for Japan to improve storage capacity? Is discharging the nuclear wastewater the only option and are there any other alternatives?

Burnie: TEPCO themselves admitted in 2019 there was sufficient storage space on the site; and the committee of the Japanese government concluded in February 2020 that storage space was available outside the perimeter of the Fukushima Daiichi site in Futaba and Okuma. As we concluded in our Greenpeace, Stemming the Tide October 2020 report, "There is no technical, engineering or legal barrier to securing storage space for ALPS-treated contaminated water. It is a matter of political will. But the decision by the government to dismiss the storage option is based on expediency - the least expensive option is to discharge into the Pacific Ocean."

GT: How can the international community and relevant organizations resolutely resist Japan's discharge of contaminated water? What is the significance of this?

Burnie: It is not inevitable that the contaminated water will be discharged into the Pacific Ocean. The Japanese government is under significant domestic and international pressure not to discharge - and importantly, there are alternatives to discharge - specifically long term storage and application of the best available technology to processing and remove radioactivity including tritium from the water. The Japanese government/TEPCO have recently announced a request for proposals for technology to remove radioactive tritium from the contaminated water - this would not have happened with the concerns of citizens NGO's and governments.

It's important to question all aspects of the Japanese government's plans as Greenpeace is doing: Challenge the deadline of 2022/23 - there is storage space; call for best available technology to be used - both for ALPS and for tritium and carbon 14 removal; build more robust storage tanks; confirm that radioactive tritium and carbon 14 in the discharge water has environmental and health consequences.

Continuing to raise these issues, including consideration of legal aspects under the United Nations London Convention and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea are important for all concerned parties to consider.