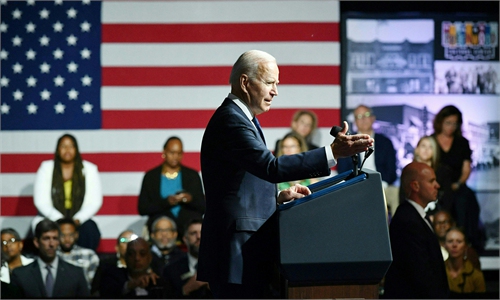

Members of the Black Panther Party and other armed demonstrators rally in the Greenwood district during commemorations of the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre on Saturday in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the US. Photo: AFP

When the history is inglorious, the first instinct of the United States is to bury it with everything at disposal - shovels, bulldozers and political manipulation. A century later, the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921 finally came to public attention. The horror is not a bit less. The wealthiest US Black community of Greenwood, Tulsa, was burned into ashes. An estimation of 300 Black Tulsans died and nearly 10,000 were displaced amid hours of fire and smoke. White mobs attacked with weapons supported by local authorities and with impunity. The tragedy is finally brought to daylight. Still, no one has been held accountable and zero compensation made.How could this issue be hidden from the public for generations? Is the cover-up removed now? To find the answer, one needs to check not what has been said, but what has been done.

Gatekeeping or erasing evidence

There is nothing wrong with the concept of gatekeeping per se. But when all access to certain information is denied, that raises an alarm bell. Dead bodies were buried or discarded into rivers. Documents and newspaper were destroyed by local authorities. The atrocity remained banned from the school curriculum and the textbooks of local public schools in Oklahoma before 2000. For such reasons, the official number of victims in the Tulsa Massacre has not yet been confirmed. Most young Black Tulsans learned in disbelief what their hometown had gone through from people outside the State of Oklahoma.

Consoling or muzzling victims

Silence was the only answer to any inquiry of the Tulsa Massacre. Some say, let wounds heal by not mentioning the past. But the gag policies tell a different story. Locals who talked about the history faced life threats. Immigrants were warned not to discuss it. Some survivors went to the Tulsa District Court for compensation. The appeal was dismissed and they were not allowed to sue within two years. Another lawsuit at the Federal High Court did not meet any luck either.

Rebuilding or ripping apart the community

The race massacre, though tragic, did not kill local Black Tulsan's initiative to revive their community. The neighborhood survived, only to be ultimately destroyed by a more unrelenting foe: infrastructure development plans. Local government raised the standard of reconstruction of the community to a level above what the Black residents could afford. The federal government also listed the Greenwood community as a "dangerous area", making it impossible for homeowners to apply for mortgage. Eventually, those who call the land home were forced out; the government claimed the land for its own purpose.

In late 1960s with federal funding, highways were built through North Tulsa. As in so many other US cities, freeway was constructed to divide and isolate communities of color. Like a sword that cut through the heart, Greenwood was demolished and depopulated. The new Interstate 244 on the one end cordoned off the community with an old rail line on the other. The big overpass also shadows the very buildings that were described as "once a Mecca for the Black businessman". The previous downtown area can hardly make a transit now.

While North Tulsa is dying, the South is thriving. Some in the South even advocate for turning the memorial of the Massacre into a tourist attraction for more profits. The two sides of the traffic route are divided into disparate conditions. The Black identity that used to unite the people together against oppression from the White community is shattered by the widening wealth gap allowed by the US government.

Beyond burying the Massacre, the US was and still is reshaping the collective memory. It is no longer about cover-ups but the destruction of history. Americans are living with racial tension as part of their daily life. But history taught them little about the country's racial endemic. The only three survivors from the bloodshed - all above the age of 100 - are witnessing the disappearance of evidence and drainage of insistence on truth and justice.

The author is a commentator on international affairs. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn