G20 Photo:VCG

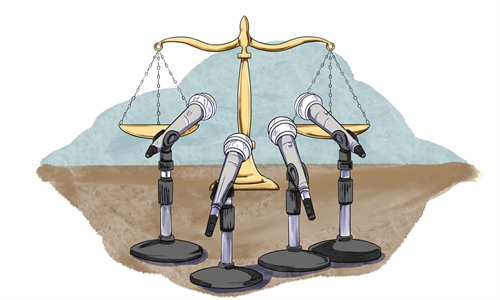

While Western countries are actively pressing ahead with the largest overhaul of the international tax system in a century, whether developing countries will benefit from the redistribution of the global corporate taxation will be an inescapable question for the plan.Finance ministers and central bank governors across the G20 countries issued a joint communiqué endorsing the global minimum tax plan after meeting in the Italian city of Venice on Saturday.

The communiqué called the new tax deal "a historic agreement on a more stable and fairer international tax architecture" and called on all countries in the negotiations to "swiftly address the remaining issues and finalize the design elements" by the next G20 meeting in October, according to media reports.

The development marks the most recent progress after G7 nations agreed on the new tax deal last month and 130 countries backed it at talks hosted by the OECD in Paris at the beginning of July.

On the surface, setting a global minimum tax report of at least 15 percent is aimed at putting an end to abuse of tax havens, as well as extracting more tax revenue from tech giants as well as other multinationals that have eroded the tax base. Yet, it is not hard for some observers reading through the media reports about the new tax plan to realize that these complex tax rules are actually designed to collect more taxes from multinationals.

While the new global tax rules have not been fully finalized, recent progress regarding the fundamental changes to the international tax system still gives the impression that the rules which form the global tax architecture were largely being decided by a group of developed countries, with the developing world being more passive and slow to respond to the overhaul which could potentially strike a major blow to their own taxation jurisdiction.

In fact, some observers already found that many of the new tax rules may have the potential to have big impacts on corporate tax revenues in developing countries. For instance, the global minimum tax of 15 percent may means that tax incentive policy adopted by many countries may no longer be helpful in attracting foreign investment.

Moreover, there are concerns that the complex allocation of profits to jurisdictions based on the arbitrary allocation between residual and routine profits may also impact the interests of developing countries.

It is also a hammer blow for many developing countries that they will have only limited options to tax Western tech giants and are asked to accept mandatory arbitration of disputes upon signing up to the OECD agreement.

Of course, the current deal is not the final. If anything, developing countries need to actively participate in the follow-up negotiations on the new tax rules so as to struggle for more beneficial details such as the base of profits subject to the minimum tax and the way of reallocating taxing rights. A more inclusive global mechanism is needed to invite more low-income developing countries to raise their concerns and requests for the deal. The new tax deal will never work globally if poor countries deem that it is just attempt by rich countries trying to deprive them of tax revenue.