Stories of Separation and Reunion in China-Japan Friendship — Marshal Nie Rongzhen and His Japanese "Daughter"

On the afternoon of August 24, 2005, Nie Li and Kato Mihoko greeted and hugged each other like sisters in front of the office building of the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, three years after their last encounter, and walked hand in hand into the meeting room.

However, the "sisters" had no blood ties whatsoever. Their story started with Nie Li's father — Marshal Nie Rongzhen.

In August 1940, the Eighth Route Army launched the Hundred Regiments Offensive in Northern China. In Jingxing Coal Mine, the Japanese fuel base along the Zhengding-Taiyuan Railway that was engulfed in fire, Chinese soldiers found little Mihoko and her baby sister wailing in desperation over the body of their deceased mother. Under Commander Nie Rongzhen's instruction that "children committed no crime, and should be sent to the command post," the girls were escorted to the front-line command post in Honghecao Village. Commander Nie said that the children were innocent, and everyone should understand that although the enemy had slaughtered countless Chinese compatriots and children, we must never hurt the Japanese people or their children. During her stay in the command post, Mihoko would drag Commander Nie's clothes and follow him wherever he went. And Commander Nie would feed her porridge and pear slices, and send military doctors to treat her and her sister, just like a father.

However, for the sake of the girls' safety, Commander Nie could not continue raising them amid fierce fighting. They had nothing to do with the war, and should therefore return home safely. Commander Nie decided to send the two girls back to the Japanese military camp. On the day before their separation, Commander Nie held Mihoko's hand and said softly, "Good girl, do you miss home? Come on, let's take a photo, and I'll send you back tomorrow." Sha Fei, then deputy head of the newspaper Kangdibao (literally "Resistance News") swiftly captured this moment with a precious photo.

Commander Nie got up very early the next morning. He wrote a letter condemning the Japanese invaders' crime and demanding that the Japanese side take good care of the girls. In his letter, Commander Nie denounced the four-year Japanese aggression into China that had left countless people of both countries dead, wounded, disabled, and homeless, and stressed that the Japanese invaders should take full responsibility for all these tragedies. He went on to write about the two girls, hoping that they could go back to their families and stay away from the war. Commander Nie ended that letter stating solemnly that the Eighth Route Army was committed to internationalism, compassion and justice, and was determined to fight for the survival of the Chinese nation and the enduring peace of humanity.

Militia and army troops then escorted Mihoko and her sister to the Japanese military camp in Shijiazhuang amid heavy fighting. Sadly, the younger sister who was barely one year old died in a Japanese military hospital in Shijiazhuang, while Mihoko was brought back to Japan safely. Mihoko was too young to clearly remember all that had happened. After returning to Japan, she was cared for by relatives, and nobody knew what had happened to her in China. However, she managed to recall from time to time to her grandmother things like eating pears and sitting in a basket.

Fast-forward to May 1980, the People's Daily carried an article titled Little Japanese Girl, Where Are You? written by Yao Yuanfang, then deputy head of the PLA Daily, and people came to know about Marshal Nie's adoption of two Japanese orphans. On the next day, Japan's Yomiuri Shimbun published the headline Kyouko Sisters, Where Are You? General Nie Rongzhen Is Calling Orphans Rescued amid Gunshots 40 Years Ago, a story of the Chinese Marshal's humanistic rescue of war orphans that spread across Japan. Thanks to the all-out efforts of friendly Japanese, "Kyouko", or Kato Mihoko, was found in Kyushu in less than a week's time. She was then already married with three children, and ran a grocery store with her husband.

On July 10 of the same year, 43-year-old Mihoko visited China again in a Japanese goodwill delegation. She had no idea that she would be greeted in the airport of Beijing like a head of state. Yao Yuanfang, then deputy head of the PLA Daily, welcomed her back to her "second hometown" and hoped that she would feel at home. Nie Li, Marshal Nie's daughter, patted on her shoulder and said, "I'm so happy to see you. My father has been waiting for you. Here are some homegrown roses and sweet flags for you." Mihoko couldn't help but sobbing in Nie Li's arms in deep emotions.

On July 14, Marshal Nie met with Mihoko in Xinjiang Hall of the Great Hall of the People, 40 years after separation. The reunion of the father and daughter was a deeply moving scene. Marshal Nie said to Mihoko that China and Japan were neighbors linked by a narrow strip of waters, and there was no reason for unfriendly sentiments. To develop friendship between the two peoples is of great significance, and only with closer people-to-people exchange could the bond and friendship between them be strengthened. We Chinese and Japanese must carry forward this friendship from generation to generation.

After that reunion, Mihoko became a special messenger for China-Japan friendship, and visited China many more times including in 1986 and 2002, devoting to promoting friendship between the two peoples. Mihoko and General Nie Li became close sisters, and Mihoko's hometown Miyazaki of Miyakonojo and Marshal Nie's hometown Jiangjin of Sichuan Province also became sister cities.

Mihoko's story was just a miniature of Japanese war orphans in China. In August 1945, as the Soviet Red Army launched fierce offensives on the Kantogun army, Japan attempted to use its 270,000 "Pioneer Corps" settlers to hold back the attacks. Before its surrender, an internal armistice report of the Japanese military cruelly ordered that nobody except wounded soldiers would be allowed to return to Japan. As a result, by 1950, there were still more than 50,000 Japanese stranded in Northeastern China, including a large number of war orphans, most of whom were from ordinary Japanese households. The Chinese people kindly extended their helping hands to these poor orphans, bringing them up and sending them to schools. In the 1980s, as China's economy took off and China-Japan relations improved, the war orphans began to return to Japan and search for their families. Throughout all these years, many were impressed by China's generosity, and by the admirable benevolence of Marshal Nie as well as many other Chinese foster parents.

However, the "sisters" had no blood ties whatsoever. Their story started with Nie Li's father — Marshal Nie Rongzhen.

Nie Li (right) presents Kato Mihoko a calligraphic work.

In August 1940, the Eighth Route Army launched the Hundred Regiments Offensive in Northern China. In Jingxing Coal Mine, the Japanese fuel base along the Zhengding-Taiyuan Railway that was engulfed in fire, Chinese soldiers found little Mihoko and her baby sister wailing in desperation over the body of their deceased mother. Under Commander Nie Rongzhen's instruction that "children committed no crime, and should be sent to the command post," the girls were escorted to the front-line command post in Honghecao Village. Commander Nie said that the children were innocent, and everyone should understand that although the enemy had slaughtered countless Chinese compatriots and children, we must never hurt the Japanese people or their children. During her stay in the command post, Mihoko would drag Commander Nie's clothes and follow him wherever he went. And Commander Nie would feed her porridge and pear slices, and send military doctors to treat her and her sister, just like a father.

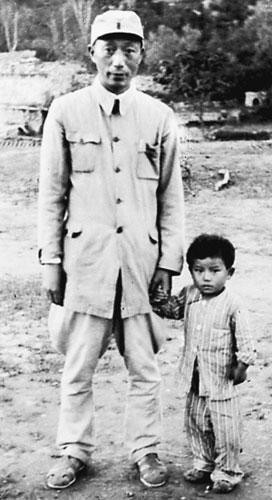

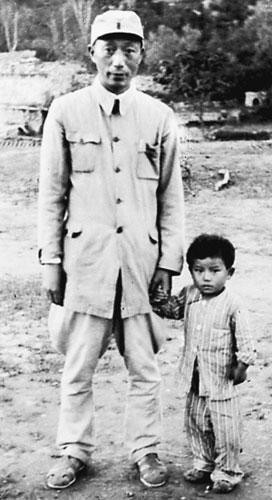

However, for the sake of the girls' safety, Commander Nie could not continue raising them amid fierce fighting. They had nothing to do with the war, and should therefore return home safely. Commander Nie decided to send the two girls back to the Japanese military camp. On the day before their separation, Commander Nie held Mihoko's hand and said softly, "Good girl, do you miss home? Come on, let's take a photo, and I'll send you back tomorrow." Sha Fei, then deputy head of the newspaper Kangdibao (literally "Resistance News") swiftly captured this moment with a precious photo.

Nie Rongzhen and little Kato Mihoko

Commander Nie got up very early the next morning. He wrote a letter condemning the Japanese invaders' crime and demanding that the Japanese side take good care of the girls. In his letter, Commander Nie denounced the four-year Japanese aggression into China that had left countless people of both countries dead, wounded, disabled, and homeless, and stressed that the Japanese invaders should take full responsibility for all these tragedies. He went on to write about the two girls, hoping that they could go back to their families and stay away from the war. Commander Nie ended that letter stating solemnly that the Eighth Route Army was committed to internationalism, compassion and justice, and was determined to fight for the survival of the Chinese nation and the enduring peace of humanity.

Militia and army troops then escorted Mihoko and her sister to the Japanese military camp in Shijiazhuang amid heavy fighting. Sadly, the younger sister who was barely one year old died in a Japanese military hospital in Shijiazhuang, while Mihoko was brought back to Japan safely. Mihoko was too young to clearly remember all that had happened. After returning to Japan, she was cared for by relatives, and nobody knew what had happened to her in China. However, she managed to recall from time to time to her grandmother things like eating pears and sitting in a basket.

Nie Rongzhen sends Mihoko back.

Fast-forward to May 1980, the People's Daily carried an article titled Little Japanese Girl, Where Are You? written by Yao Yuanfang, then deputy head of the PLA Daily, and people came to know about Marshal Nie's adoption of two Japanese orphans. On the next day, Japan's Yomiuri Shimbun published the headline Kyouko Sisters, Where Are You? General Nie Rongzhen Is Calling Orphans Rescued amid Gunshots 40 Years Ago, a story of the Chinese Marshal's humanistic rescue of war orphans that spread across Japan. Thanks to the all-out efforts of friendly Japanese, "Kyouko", or Kato Mihoko, was found in Kyushu in less than a week's time. She was then already married with three children, and ran a grocery store with her husband.

On July 10 of the same year, 43-year-old Mihoko visited China again in a Japanese goodwill delegation. She had no idea that she would be greeted in the airport of Beijing like a head of state. Yao Yuanfang, then deputy head of the PLA Daily, welcomed her back to her "second hometown" and hoped that she would feel at home. Nie Li, Marshal Nie's daughter, patted on her shoulder and said, "I'm so happy to see you. My father has been waiting for you. Here are some homegrown roses and sweet flags for you." Mihoko couldn't help but sobbing in Nie Li's arms in deep emotions.

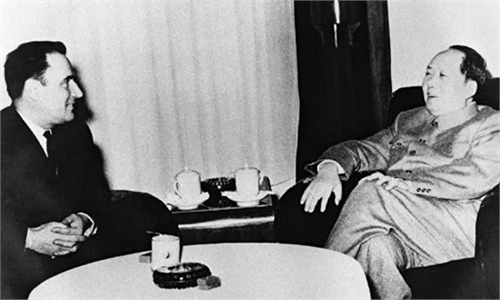

On July 14, Marshal Nie met with Mihoko in Xinjiang Hall of the Great Hall of the People, 40 years after separation. The reunion of the father and daughter was a deeply moving scene. Marshal Nie said to Mihoko that China and Japan were neighbors linked by a narrow strip of waters, and there was no reason for unfriendly sentiments. To develop friendship between the two peoples is of great significance, and only with closer people-to-people exchange could the bond and friendship between them be strengthened. We Chinese and Japanese must carry forward this friendship from generation to generation.

Reunion of Marshal Nie Rongzhen and Mihoko

After that reunion, Mihoko became a special messenger for China-Japan friendship, and visited China many more times including in 1986 and 2002, devoting to promoting friendship between the two peoples. Mihoko and General Nie Li became close sisters, and Mihoko's hometown Miyazaki of Miyakonojo and Marshal Nie's hometown Jiangjin of Sichuan Province also became sister cities.

Mihoko's story was just a miniature of Japanese war orphans in China. In August 1945, as the Soviet Red Army launched fierce offensives on the Kantogun army, Japan attempted to use its 270,000 "Pioneer Corps" settlers to hold back the attacks. Before its surrender, an internal armistice report of the Japanese military cruelly ordered that nobody except wounded soldiers would be allowed to return to Japan. As a result, by 1950, there were still more than 50,000 Japanese stranded in Northeastern China, including a large number of war orphans, most of whom were from ordinary Japanese households. The Chinese people kindly extended their helping hands to these poor orphans, bringing them up and sending them to schools. In the 1980s, as China's economy took off and China-Japan relations improved, the war orphans began to return to Japan and search for their families. Throughout all these years, many were impressed by China's generosity, and by the admirable benevolence of Marshal Nie as well as many other Chinese foster parents.