Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The abolition of slavery in Canada was officially recognized nationwide for the first time on Sunday. Even though slavery was abolished in the British colonies, including Canada in 1834, it had taken nearly 200 years before members of Parliament voted to designate August 1 as Emancipation Day on March 24.Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued a statement on the day, admitting, "Today, Black Canadians continue to face prejudice, discrimination, and longstanding disparities in access to education, housing, and employment that limit their full and equal participation in society."

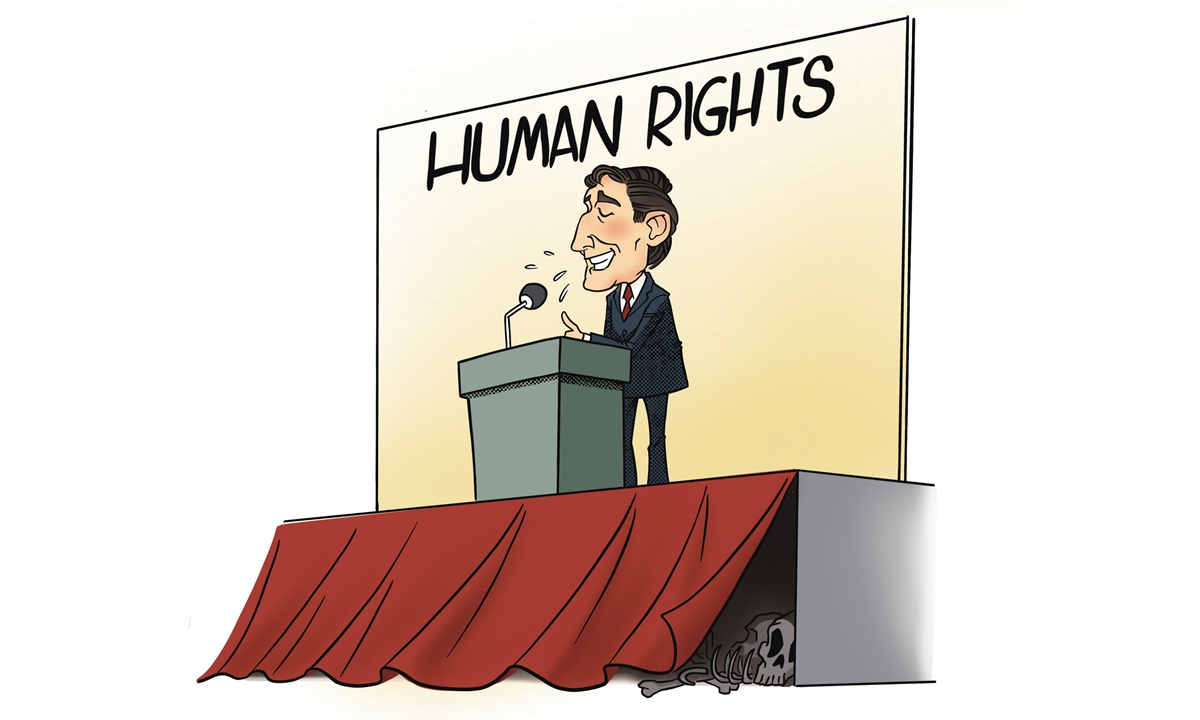

The Canadian government likes to play human rights card internationally, and has formed an image as a bastion of human rights. However, the fact that it took so long to recognize the emancipation at the federal level is a powerful illustration of Ottawa's hypocrisy over human rights.

Why has it taken such a long time before the day is officially recognized? Why is it that Canada's political parties only seem to be opening up to recognizing the widely known injustices suffered by so many of African descent in Canada? Shouldn't Canadian politicians, who often talk about human rights, have the best understanding of their country's human rights situation?

Perhaps it is because of these politicians' awareness of the truth that they have been striving to gloss over the injustices suffered by ethnic minorities such as African Canadians in order to maintain Canada's image as flag-bearer of human rights. But as the worldwide backlash against racism triggered by the murder of George Floyd had also impacted Canada, politicians have to consider how to appease the rising discontent of an increasingly awakening public.

From this perspective, Ottawa's gesture has more to do with political considerations than a genuine desire by politicians to tackle racism issues once and for all. Liu Dan, a research fellow with the Center for Canadian Studies at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, believes that Canada still has a very long way to go before it can address the racial problems or realize reconciliation.

"Racial problems are long-standing and deep-rooted. Many administrations have done something but the situation remains unsatisfactory. As the environment changes, racism, populism, and anti-globalization ideas are often intertwined," Liu noted.

Canadian historian Taylor C. Noakes wrote in the National Post in March that "far too many Canadians have held on to the belief that some cultures and societies are better than others and therefore have a right to impose their will on anyone they deem subpar." Noakes suggested that deep-rooted white supremacy is the key issue that hinders many Canadians from going straight. Against such a backdrop, "institutional and systemic forms of racism" affirmed by Trudeau has long been targeted at non-White ethnic groups in addition to those of African descent.

Just days before this year's Emancipation Day, in a park in Surrey, a city in British Columbia, an angry couple took garbage out of the trash can and started throwing it at South Asian people, including the elderly and children, who were gathering in the park. The couple also shouted at them, "We're in Canada, speak English, don't you speak English?"

Shockingly, when a police officer eventually came to attend to the case, the officer simply said, "Maybe they [the couple] were just having a bad day." The skin color of the couple and the officer was not mentioned in media reports. Nonetheless, such an attitude and behavior clearly reflect many Canadians' ignorance and indifference to racism. With such being the case, how can racial problems in Canada be properly addressed?

It is hoped that Canada can put words and deeds together so that Emancipation Day can truly be the beginning of addressing the racial problems in Canada, rather than just another meaningless political show.