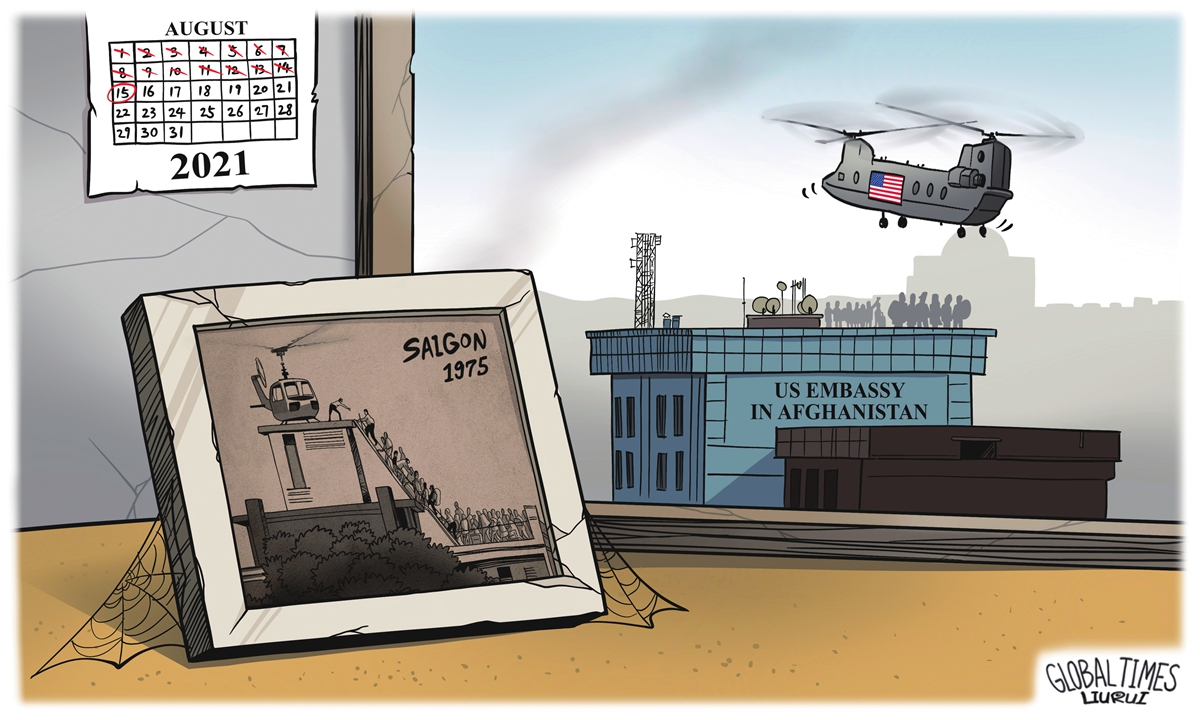

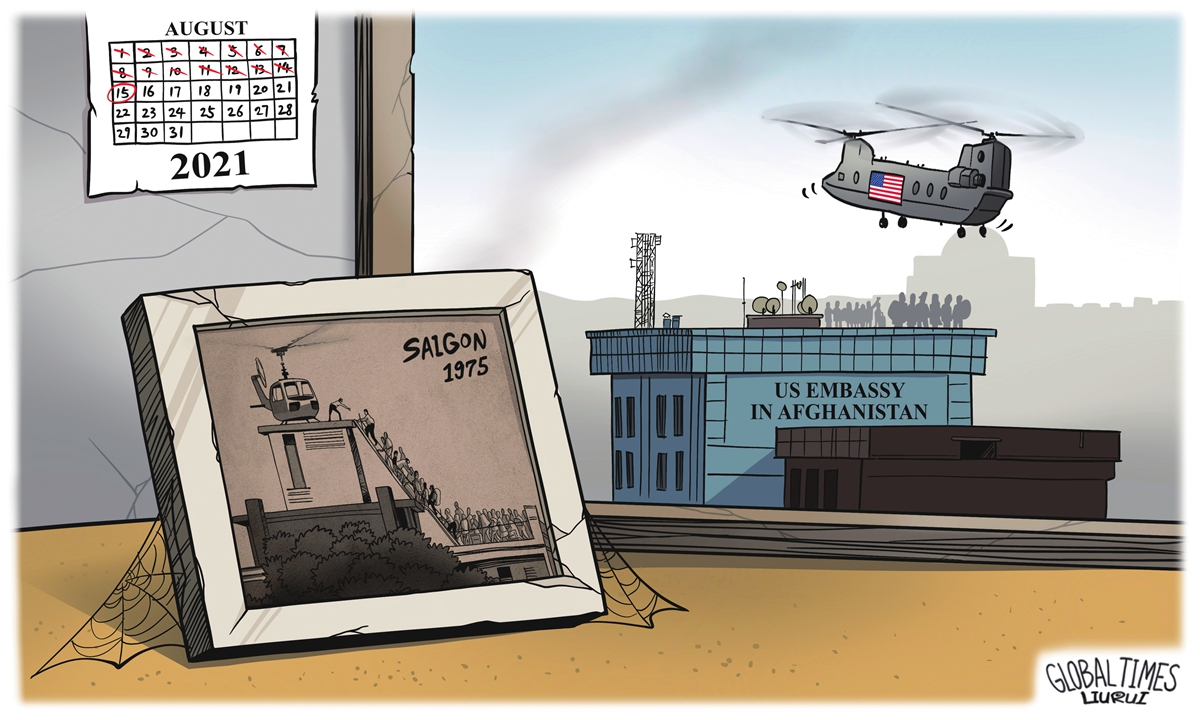

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

August 15, the day that marked the 76th anniversary of Japan's unconditional surrender in World War II, also witnessed the capital of Afghanistan being taken over by the Taliban at a stunning speed and with almost no bloodshed.

US' practices in Afghanistan, which began in 2001 and ended in 2021, as well as US setbacks there, can be viewed as the end of the second period of US strategic profligacy. The first period took place when US decided to intervene in the civil war of Vietnam militarily, trying to establish a so-called model of Western democracy in southern Vietnam, in an attempt to resist the "expansion of Communism" on the Indochinese Peninsula and in Southeast Asia. It ended with an embarrassing evacuation from Saigon in 1975.

The history of US hegemony after 1945 is roughly the following cycle: expansion - profligacy - contraction - buildup of strength - expansion. After withdrawing from Vietnam, the US learned its lesson and behaved itself for a short while.

But obviously, it rushed into a new round of strategic profligacy in 2001. Core decision-makers in the US government no longer pursued a clear and functional goal, but were trapped into a swamp of trivial and endless puzzles. They have been treating US strategic strength and resources as a blank check and expending it without limit.

In the past 20 years, Washington has spent more than $2 trillion on the war in Afghanistan. According to Forbes, this includes $800 billion in direct war-fighting costs and $85 billion to train more than 300,000 Afghan forces. Last Wednesday, a US defense official said that the Taliban would take over Kabul within 90 days. However, the Taliban vanquished the Afghan government army that the US and its allies spent 20 years working to build in less than 10 days.

No matter who is in office in the US - either Donald Trump or Joe Biden, the task the US president faces is to end Washington's strategic profligacy decently and enter a new period of contraction and buildup of strength. If the US is lucky enough, it might even take the chance to truly "make America great again."

In 1975, the evacuation of the US Embassy in Saigon demonstrated the power and efficiency of the fine operation of a giant war machine that a superpower should have. At that time, around 28 ships participated in the evacuation, including at least four aircraft carriers. However, this time in Kabul, it was a temporary combination of impromptu responses: Not only did the security forces in Afghanistan collapse quickly, but also the US Embassy fled Kabul helter-skelter.

And it is not only a question about Washington's image. More importantly, it reflects that there are no longer any experts in the core circles of strategic decision-making who know how US troops could leave Afghanistan properly - in a way that can not only balance the political considerations of US leadership but also maintain the decency and dignity the US needs to show as a superpower.

The US at the moment will certainly focus on exploring various ways to make up its deficiency. Dramas may continue to play out at Kabul International Airport, the only exit route for the US and the rest of the world. But other global actors, when they witness Kabul's "Saigon moment" through the haze above the city, may ask: How much capacity does the US still have to stay in its position as the so-called leader to lead its partners to meet various challenges? Could such a US government that has ridiculously withdrawn its troops from Afghanistan, let alone construct it, really be at the core of Western leadership in dealing with global challenges? Any rational person needs to think about this.

Lastly, people must remain deeply aware of the fact that strategic changes and a major turning point have been taking place. For Washington, reproducing the experience of the Cold War will not help it overcome the discomfort caused by its contraction from strategic profligacy. It may even fall into a stage of accelerated loss of hegemonic strategic resources due to wrong perceptions caused by emotions and stereotypes. It's hoped that Washington could have the wisdom to move on from this flawed perception and outdated mentality, and end this period of strategic profligacy in a right and decent way. This is not a bad thing for anyone, especially the US.

The author is professor at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs of Fudan University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn