Nobel Physics Prize honors climate work, setting global warming alarm

Preparations take place at Stockholm's City Hall to convert the venue for the Nobel Prize banquets into a COVID-19 vaccination centre for a day on February 21 in the capital of Sweden, amid the novel coronavirus. Photo: VCG

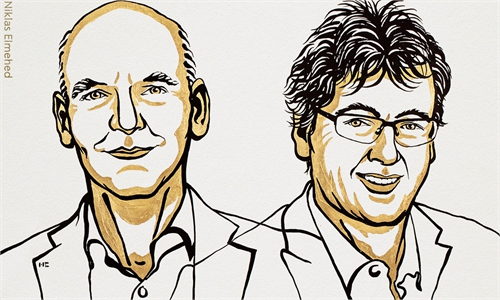

Japanese-American scientist Syukuro Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann of Germany and Giorgio Parisi of Italy won the Nobel Physics Prize for climate models and the understanding of physical systems, a message weeks before the COP26 climate summit as the rate of global warming sets off alarm bells around the world.

"The world leaders that haven't got the message yet, I'm not sure they will get it because we are saying it," said Thor Hans Hansson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics. "What we are saying is that the modeling of climate is based in physics theory."

Manabe, 90, and Hasselmann, 89, will share half of the 10 million kronor ($1.1 million) prize for their research.

Parisi, 73, won the other half for his work on the interplay of disorder and fluctuations in physical systems.

"Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann laid the foundation of our knowledge of the Earth's climate and how humanity influences it," the Nobel Committee said. "Giorgio Parisi is rewarded for his revolutionary contributions to the theory of disordered materials and random processes," it added.

Manabe, who left Japan for the US in the 1950s, is affiliated with Princeton University, while Hasselmann is a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg.

Parisi, who also won the prestigious Wolf Prize in February, is a professor at Rome's Sapienza University.

Working in the 1960s, Manabe showed how levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere correspond to increased Earth surface temperatures. Crucially, he recognized the role of water vapor in trapping heat, which is much more than carbon dioxide alone.

Manabe's seminal models, carried out at a time when computer power was a fraction of what they are today, remain a blueprint for the field.

But at the time he had little idea of his work's critical importance, telling reporters at a press event at Princeton, New Jersey, that he carried out his research "because I really had great fun."

Hasselmann was credited for working out how climate models can remain reliable despite sometimes chaotic variation in weather trends.