Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Since the Biden administration took office, the word "ally" has become a mantra of many American politicians. But in fact, for the US, making alliance is more like a business deal. The US will form alliances with other countries only when this relationship suits US' global strategy and is dominated by the US. The US-Japan alliance is the best example.Senior Japanese and US diplomats recently agreed to aim for an early visit to the US by Japan's new Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for a meeting with US President Joe Biden. Japan, like many other US allies, wants the US to support it unconditionally if the US sees Japan's sincerity. In its strategic game against China, Japan expects the US to support Japan with military force on the issues about the Diaoyu Islands, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea.

Japan believes that it is in a weak position alone against China. If it has strong support from Washington, it can use the power of the US to contain and suppress China. In fact, Japan is more afraid of China's rise than the US. It therefore wants to set up some issues that bind the US firmly in East Asia and remind the US of its "responsibility" to protect Japan and other allies. This also shows that Japan does not trust the US deep in the heart and is afraid that the US may forget Japan in the twinkling of an eye.

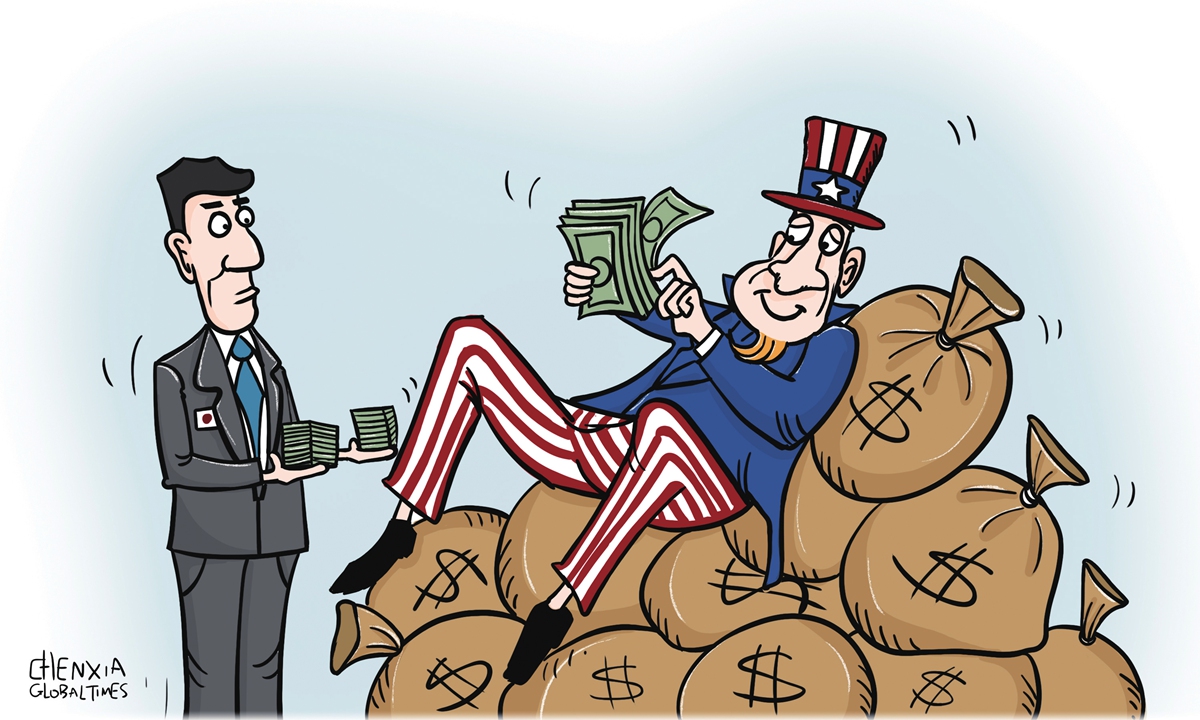

Japan is actually "inviting the wolf into the house" in East Asia. The US gains economic benefits from this alliance, and simultaneously keeps Japan firmly under its jurisdiction. While welcoming and encouraging Japan to increase its military expenditure, the US is also restricting Japan's military development. From Washington's viewpoint, Tokyo does not need to fight globally and has no need to have, for example, strategic bombers. This is why Japan has no real strategic bombers.

If Japan expands its military massively, it will no longer need American troops stationed in Japan, which will be a loss of money for the US. Why would the US allow that? After all, the US alliance strategy is more concerned with its own economic gains. Because of this, conflicts of interest between the US and its allies are bound to increase.

According to Kyodo news on November 10, Daniel Kritenbrink, assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs under the Biden administration, welcomed Japan's plan to increase its military budget. Observers analyzed that he is referring to his expectation that Japan would increase the spending to support US troops stationed in Japan.

The US certainly will welcome Japan's increase in defense budgets. With the rise of China worrying the US, Washington wants to check and balance Beijing's influence by working with Tokyo. Therefore, the US has been encouraging Japan to boost its military power, and during the process Japan will inevitably rely on American arms and technology. Hence, this can promote the sales of American arms and benefit the development of the American arms industry. In addition, it wants to urge Japan to pay more for the US military in Japan.

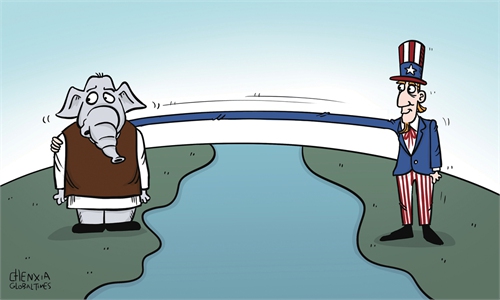

Actually, the US is not only targeting its Asia-Pacific allies like Japan and South Korea, but also asking NATO allies including Germany to pay for the US troops and increase their military spending. Why? Because the alliance is a business deal for the US. It sounds like the countries in alliance are equal, but they're not. The relationship between the US and its allies should first be suitable for the US' global strategy. Second, all allies are subordinate to the US. Although NATO is a multilateral platform, its commander is predominantly Washington while the fundamental power of NATO rests with the US. Third, the commitment between the US and its allies is based on the fact that the US may only consider sending troops to help its ally when that ally is in danger and US interests are threatened.

However, will the US send troops when an ally is in danger but the US' own interests are not touched? Absolutely not. US allies are cannon fodder for the US to achieve its own interests.

The article was compiled by Global Times reporter based on an interview with Zhou Yongsheng, a professor in the Institute of International Relations at China Foreign Affairs University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn