China’s democracy is about social concerns, not ‘who’s the coolest, who’s the handsomest’: scholars

The Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee presides over the sixth plenary session of the 19th CPC Central Committee in Beijing, capital of China. Photo: Xinhua

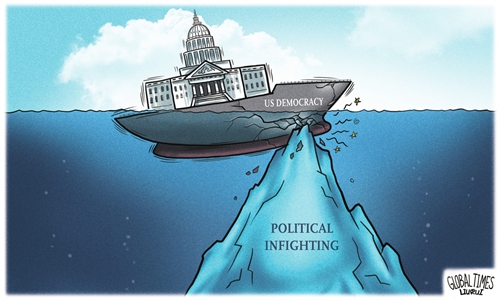

Editor's Note:The so-called Summit for Democracy hosted by the Biden administration kicked off on Thursday. Many have seen this event as an attempt to isolate China, which the US portrays as a non-democratic country. How do knowledgeable foreign scholars view China's democracy? Four scholars from Russia, the UK, the US, and Germany shared their points of view with the Global Times in this regard.

Yury Tavrovsky, head of "Russian Dream-Chinese Dream" analytic center of the Izborsk Club.

Beijing does not try to teach democracy with Chinese characteristics to other peoples. At first glance democracy with Chinese characteristics looks as unusual as Chinese characters. There is no alphabet and there are no letters in Chinese but whole words written in the form of characters. Chinese democracy also operates not with individuals but with masses of people.

China's political system today is as different from Western democracy as Chinese characters are from the Latin or Cyrillic alphabets. But it does not make this system inferior or less attractive. The Chinese call their political system "people-centered socialist democracy" and they have gained remarkable and globally eye-catching social and economic achievements. They have also developed an efficient market economy, which is the second biggest in the world. In the past 10 years they have rapidly improved the livelihoods of Chinese people and eliminated poverty for the first time in human history. Per capita GDP as well as national GDP have doubled and the middle class is now about 450 million people.

The Chinese political system for several decades has avoided populist radicalism. Despite incomes inequalities, vicious conflicts have been prevented among different social groups. Although Chinese people sometimes express opinions on the internet in a fierce manner, China's social governance has generally maintained order.

The Chinese call their political system "whole-process people's democracy" and it is firmly based on local traditions and current realities. It looks as harmonious in the Chinese political landscape as a beautiful pagoda. To challenge it with a rather shaky and dilapidated Western skyscraper is not wise and may even be dangerous.

Martin Jacques, a senior fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies at Cambridge University until recently, a visiting professor at the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua University, and a senior fellow at the China Institute, Fudan University

The West believes that its model is universal and has long sought to impose it on others. In contrast, China believes its model is not for export, that it is distinctive to China, although, that said, the developing world is seeking to learn as many lessons as it can from it.

The Western attempt, in this context, to present the future of governance as a struggle between democracy and authoritarianism entirely misses the point. The challenge facing the world, whatever the tradition of governance, is the quality and effectiveness of governance. It is on this ground that the West is losing the argument and will lose it even more decisively in the future.

China, in contrast, does have a concept of the world that is integral to the history of Chinese civilization, namely tianxia, or "all-under-heaven." In the era of globalization and climate change, a concept of the world, rather than just the nation-state is essential. That is why the Chinese proposition for a "shared destiny for mankind" is fundamental to a new way of thinking about the world and democracy.

Kenneth Hammond, professor of East Asian and global history at New Mexico State University

Western-style democracy overwhelming has been self-defined as having elections on some basis. Here in the US, we have elections at set intervals. At those intervals, voters can go to the polls, and they vote. The way that they make their decisions is strongly influenced by the money that gets spent on advertising and propaganda, and all these other things. But that is what we think of as democracy.

China's process is very different, because it's not based on this kind of public display of a political debate and then "let's pick the winner". It involves a lot of what we might consider a consultative process. They may have somewhat divergent ideas, opinions, and proposals about policies. Those things get articulated in a variety of ways. A lot of that is going on within the membership of the Communist Party of China. The thing that's difficult for people in the West to understand or work with is the idea that there's a lot of debate, discussion, contention, rivalry, and different points of view. That process in China doesn't go on the front page. In China, you don't make a big display. But instead, that process goes on, and then once decisions are reached, once a kind of consensus emerges, then the question becomes putting that into practice, and that's when things move out into the public sphere.

That's very consistent with China's traditional political culture. That idea is it's not good for people to contend with each other for who's the coolest, who's the most electable, who's the handsomest, or things of that nature. Petty interests debated in public don't make for good government. It's very different from the way things have been done here, especially in the modern period in the West. I do think it's a democratic process in China. It's not the same kind of process that we have here. But it is a process that leads to the articulation and the effective management of social concerns.

Peter Herrmann, professor at the Human Rights Centre at the Law School, Central South University, China, and member of the European Academy of Science and Arts

Democracy is about human rights. Democracy is about the climate of trust.

In the West, if there is something going wrong, when there are complaints with respect to so-called liberal rights or political rights, there is a huge outcry, in particular when it happens in countries like China, Cuba, or in Latin America. However, when the same happens to economic and social rights, no voice is heard. In many European countries, hospitals do not have sufficient capacity; important surgeries are being delayed because of the new waves of the pandemic. This is important for democracy: First and foremost, I have to survive, and then I can think about how I want to get involved.

The other thing is that of course it is not just about surviving. Human rights are about having rights to determine one's own life, the way I want to live. This is about a way of living together with others.

What strikes me here in China is "trust". When I arrived here, I didn't have my own telephone number, nor could I surf the internet. People gave me the internet connection. All I did on the internet was on their record. They trusted me not to abuse it.

I see other small things like this. Food is ordered and left on the table, in a large room or on the fences (by delivery guys). You would not trust anybody in Europe to do this. But here, people trust that others won't take it.

Human rights are about trust and trust is about having conditions in which I can trust. If I live under conditions where I have completely fend for myself, , then that is a completely different story.