Many consultations in China's whole-process democracy; 'democracy summit' is provocative to begin with: US scholar

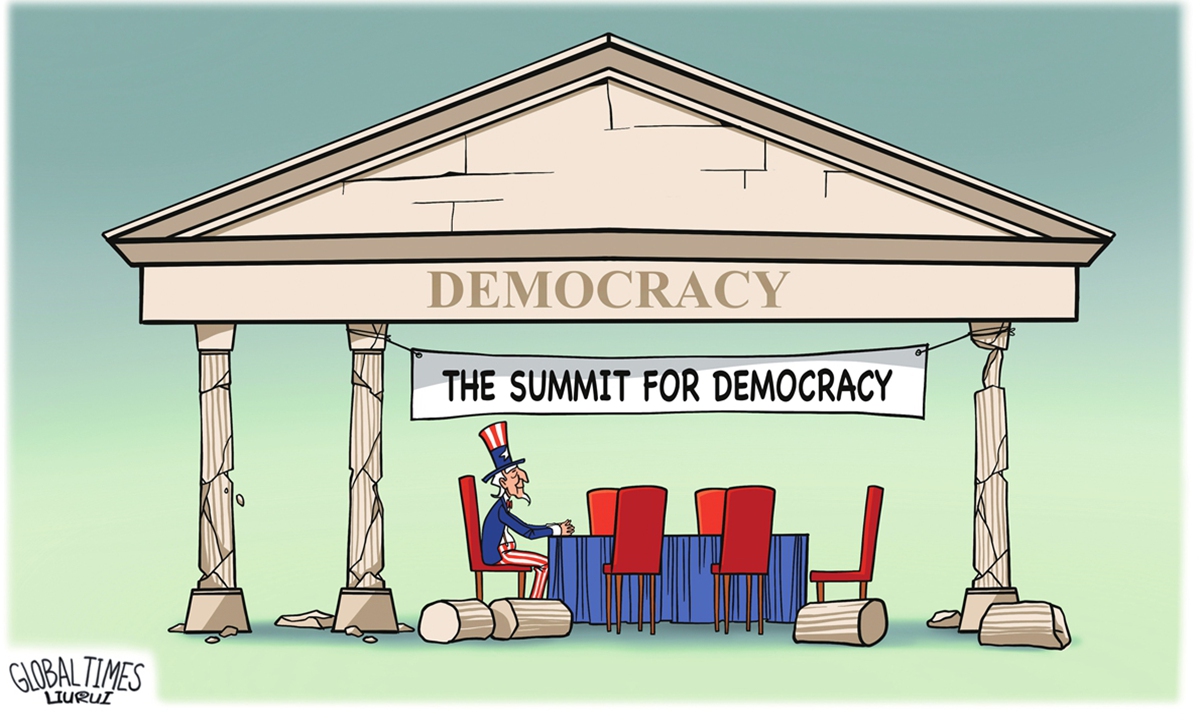

US democracy Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Editor's Note:

The "Summit for Democracy," hosted by US President Joe Biden, took place on Thursday local time amid international doubt over the US' leadership in democracy. Why is the US increasingly detached from the essence of democracy? Can the summit bolster US-style democracy around the world, and at the same time contain alleged adversarial countries like China and Russia as the US wishes? The Global Times reporter Wang Wenwen (GT) talked to Kenneth Hammond (Hammond), professor of East Asian and global history at the New Mexico State University, over these issues.

GT: In theory, a democratic system is maintained to ensure collective interests and force the political machine to self-correct. But what we have seen in the US, from the way it deals with the pandemic and the presidential election in 2020, is the evident frailty of US democratic institutions. How and why is the US detached from the essence of democracy?

Hammond: I think the way that you put it is very good - detached from the essence of democracy. The ideals of democracy are to allow the interests of the people to be articulated in their variety and for those to be addressed or attended to through the state and the government, in a way that tries to represent the complexity of society. But in the US, this isn't something brand new. This has been the nature of our system for a long time. It's gotten worse recently.

We have a constitution and a legal system which is designed to address those concerns, but it has been distorted by money and wealth. It's almost impossible for an individual to run for public office at any meaningful level up to, like, a state governor or a member of congress or anything like that, unless they're very wealthy or they have access to great amounts of money. So most political people who are politically active running for office and serving in office spend a lot of their time trying to raise money. Money becomes the overriding interest, and those people and those interests, those groups or organizations or companies that can provide money are the people that get listened to, so our democracy doesn't really function to represent the mass of ordinary people. What it winds up doing is representing the interests of those who have property and wealth in great proportions.

In the last 20 years or more because of rulings of our supreme court, corporations have been given the same political rights as actual human individuals, which means that corporations that have huge amounts of money at their disposal are active participants in our political process. All of that has distorted the democratic ideals that we profess in our country to give us a system that doesn't serve the needs of ordinary people, but that instead perpetuates the power of those who already have a lot of wealth and influence to begin with.

I think that there's a widespread understanding in the US on the part of many people that there are deep problems with our political system, that there is corruption in the sense of these kinds of structural problems. Unfortunately, most people in the US don't think that it's possible to change that American political culture. And there's a kind of belief that yes things are bad, and the system is broken, or the system doesn't serve our interest. But what can you do about it? There's nothing we can do about it. So I think there's a lot of understanding of the problem, but not a lot of faith in our ability to change it.

GT: A New Yorker article said if the Biden administration is serious about democracy, it should counter the Republicans' anti-democratic machinations. Do you think the US democratic system could bridge the divergence between the two parties?

Hammond: It's interesting that the actual working system that we have now is entirely built around these two political parties - the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. But if you go back and you read the American constitution and you look at the early history of the republic, there is no place for political parties. There's nothing about political parties in the constitution.

And in fact, I feel that the way that these political parties operate is counter to the intent of our constitution and counter to the democratic ideals that help to establish our country. The power in the country passes back and forth between these two parties - what that means in the end is that neither one of them is ultimately responsible. When the Democrats are in power, if there are problems, they blame the Republicans. When the Republicans are in power, they blame the Democrats. So it's a system that allows the power of both parties to be perpetuated by constantly shifting back and forth between them. There are some differences - the Democrats have one way of trying to do things, and the Republicans have other ways of trying to do things. But those differences are all about how best to serve and protect the interests of the wealthy and powerful people. They're not about how to take care of ordinary working people. They have deep divisions between them. That's what gets talked about in the news all the time. All we hear about is rivalries and contentions between the parties. But we never talk about how the difference between the wealthy and the powerful and the ordinary people plays out. They all pay lip service. They all talk about creating jobs and benefiting working people, but the practical realities of what they do go in exactly the opposite direction.

GT: What is your biggest worry for US democracy?

Hammond: Right now we are facing some very serious challenges to the continuing legitimacy of our political system. President Trump, when he lost the 2020 election, simply refused to accept that. We had the incident on January 6, 2021 where people who were supporting President invaded the capitol. That kind of thing is unusual to say the least here. And I think that there are real dangers that the alienation and the mistrust that many people feel will get translated not into a movement to empower ordinary people, but into the kind of movement about a great figure or a powerful leader that will further undermine real democracy. That's a very real concern.

I also think that what prevents us from solving these problems or moving forward to a more truly democratic way is this lack of faith that people have in the ability to change it. People don't believe in the possibility of an alternative. There's a saying that it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitals. People can't imagine how to go from the system that we have now that doesn't work for us to creating a system that would work for us that would serve our interests and would allow us to take care of each other.

GT: Many media outlets are pessimistic about the results of the summit, including the US media. Do you think it as proof of the world's doubt toward US leadership in democracy? Can the summit bolster US-style democracy around the world, and at the same time contain allegedly adversarial countries like China and Russia as the US wishes?

Hammond: In some ways, I'm not even sure what the point of this summit actually is. On the one hand, it's kind of a political provocation just to convene this, because you're creating a dichotomy of division saying these countries are democratic and therefore good, and those countries are not democratic and therefore bad. Right away that's creating a schism in global society where we ought to look forward to things that will draw us together.

That's a problem right in the whole concept. The idea that the US gets to be the decider to say who's good and who's bad also seems to me to be out of touch with the reality of circumstances in the world.

Today, we live in a much more multicentric and diverse world than we did decades ago. The US is kind of refusing to recognize the realities of the changes that are taking place in the world. I don't think that's very productive either. So it's not surprising many people around the world have expressed their concern to say the least about this. I think it indicates that there's a real questioning of the legitimacy of American claims to be the arbiters of who's democratic and who's not.

Democracy is not just a matter of whether you have multiparty elections. Democracy is about finding ways or whatever institutions you can create to allow the interest of ordinary people to be articulated and taken care of. Our electoral system is pretty broken and distorted. I don't think it's the most effective mechanism for achieving that. And I don't think that using the electoral process as the one and only defining feature of what's democratic and what's not is a realistic approach to understanding the way the world works today.

Restoring US leadership in democracy and containing China are part of why this summit is being organized by the US. I don't think that's going to be an ultimately effective strategy. I think it is a defensive move. It's trying to hang on to a position which really the US has already seen erode considerably. The US is not a sole superpower. It's not the only decision-making source in the world. It doesn't run the world the way that it tried to do even just maybe 20 or 30 years ago. The world is changing very quickly and this kind of trying to hang on to the past is a futile undertaking. I don't think in the long run, it's going to change the tide of history. The changes taking place in the world today are structural, fundamental.

Rather than trying to hold things back, if President Biden wants to convene a summit, why not convene a summit of all the important people in the world to talk about how we can work together to make it a better world for everyone? Setting up this kind of polarity and opposition is not going to work. It's a counterproductive effort to begin with.

GT: The US always uses the word authoritarian to describe China. However, the word has increasingly gotten used by US media and scholars to describe the US itself. How do you see this trend?

Hammond: The term authoritarian is one of those value-packed words that we use in American political culture to criticize the governments that we don't agree with. It's not used in a very technically precise way. We give a lot of support to many countries where the state system and the leadership is clearly authoritarian, but we don't call them authoritarian.

But China, which has a political system that is, in fact, very different from that of the US, has its own history and political culture, and it has a system that functions well for it. It's clearly very different from what we have in the US. Rather than try to understand that system and how it operates and the ways in which it is able to articulate the needs of people and deal with them, it's easier to take a very superficial view, without making any real effort to understand the nature of the political process and leadership and activity within the system.

The US uses its own system as the template. Anyone that diverges from that, if we don't approve of them, we will then call an authoritarian. If we're friends with them, we just don't talk about it. So there's a very opportunistic element to that.

The idea that many people are starting to question whether the US is moving in a more authoritarian direction is a very important one. As we were talking about a little bit earlier, there's a real danger in the US these days of the frustration and the unrest that many people feel. They see the system as unjust and favoring certain elites. Unfortunately, many people, instead of thinking about how we can empower ourselves, look for a strong leader, someone like, in their view, President Trump, and want to invest their interests in that figurehead. That is how you wind up with an authoritarian system.

It's short-sighted and self-serving for American leaders to point the finger and blame other countries for authoritarianism when they seem rather incapable of dealing with that threat here at home.

GT: China has been promoting and practicing whole-process democracy. In your view, how does it differ from Western-style democracy? How does it fit into China's reality?

Hammond: Western-style democracy overwhelming has been self-defined as having elections on some basis. Here in the US, we have elections at set intervals. At those intervals, voters can go to the polls, and they vote. The way that they make their decisions is strongly influenced by the money that gets spent on advertising and propaganda, and all these other things. But that is what we think of as democracy.

China's process is very different, because it's not based on this kind of public display of a political debate and then "let's pick the winner." It involves a lot of what we might call a consultative process. They may have somewhat divergent ideas, opinions, and proposals about policies. Those things get articulated in a variety of ways. A lot of that is going on within the membership of the Communist Party of China. The thing that's difficult for people in the West to understand or work with is the idea that there's a lot of debate, discussion, contention, rivalry, and different points of view. That process in China doesn't go on the front page. In China, you don't make a big display. But instead, that process goes on, and then once decisions are reached, once a kind of consensus emerges, then the question is putting that into practice, and that's when things move out into the public sphere.

That's very consistent with China's traditional political culture. If you think I don't want to get too esoteric, but if you think back to the Song Dynasty and you think back to a figure like Ouyang Xiu who wrote a very important essay, Discourse on Factions. That idea is it's not good for people to contend with each other for who's the coolest, who's the most electable, who's the handsomest, or things like that. Petty interests debated in public don't make for good government. What you need is people who are committed to the public good and are going to work, not to advance their individual or even their group interest, but to find the things that are going to work best for society as a whole. I think that's the tradition that is deeply rooted in Chinese culture. It's very different from the way that things have been done here, especially in the modern period in the West. I do think it's a democratic process in China. It's not the same kind of process that we have here. But it is a process that leads to the articulation and the effective management of social concern.