Illustration: Xia Qing/Global Times

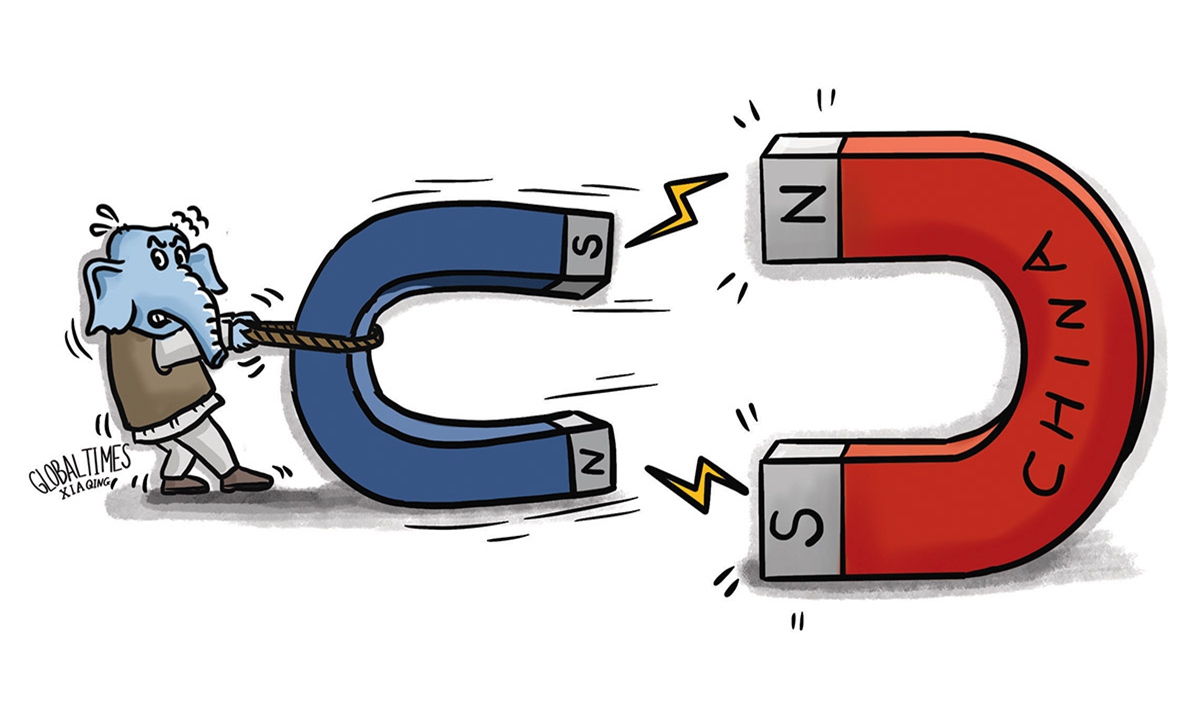

India appears to be showing a sense of unusual urgency in expanding its trade network these days, in contrast to its long-held protectionist stance. However, India must understand clearly that any attempt to exclude China, the world's second-largest economy and biggest trading nation, will seriously hamper its quest for influence in global trade.In the latest effort, India is launching free trade agreement negotiations with the UK, with the first round of talks expected to start next week, according to a statement from the UK's Department for International Trade.

A few days earlier, India agreed to remove a decades-old barrier to allow imports of US pork and pork products to its market. India is in the midst of negotiations for an interim free trade agreement with Australia. It has initiated similar talks with the EU and Canada. New Delhi also hopes to ink a free trade agreement with the United Arab Emirates in early 2022, according to Indian media reports.

The developments seem to be a far cry from the Modi government's previous wariness and resistance to free trade deals. India has opted to pull out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP, because of concerns that a considerable tariff cut would deal a severe blow to its domestic agriculture and manufacturing sectors.

But now it seems that the Indian government has changed its views on free trade deals, perhaps because it finally realized the importance of free trade for the Indian economy as well as its need for better access to global markets.

It is also worth noting that since India has always regarded China as a strategic rival, the South Asian nation may be more inclined to build a trading system that can resist regional economic influence. In this sense, India's trade efforts could be seen as a sign of its intention to counter China's economic influence in the region, especially as the RCEP took effect and tensions between China and India still persist.

But what India needs to understand is that regional cooperation actually does not conflict with India's ambition of moving up in the global industrial chain. Compared with building its own isolated industrial chain, integrating into the Asian industrial chain, which is centered around economies such as China, Japan and South Korea, points to a more practical and realistic approach for its economic development.

For instance, India's textile exports to the US surged in 2021, grabbing market share of Chinese textiles in the US amid China-US tensions. From another perspective, however, Vietnam and India are the two largest importers of sewing machines from China. The example of competition based on cooperation helps show why India needs to consider strengthened cooperation with regional economies like China as a better option.

If the Indian economy opts to develop using an export-led model, then such a growth model will be similar to the rise of China's or Vietnam's economies, which makes use of the regional industrial chain to give rise to its comparative advantage of low labor costs.

It is a good start for India to actively pursue free trade deals with the UK and other trading partners. But more importantly, it needs to attach importance to regional cooperation to support its free trade ambitions.