COMMENTS / EXPERT ASSESSMENT

Development of India's digital economy limited by protectionist policies

A general storel advertises the use of the Google Pay digital payment system in Mumbai, India, on July 17, 2021. Photo: VCG

Google India's Vice President, Sanjay Gupta, said at the recent India Digital Summit that "the startups and the digital ecosystem will really game-change the digital economy of this country [India] - to go from $250 billion to a $1 trillion economy, contributing to more than half the growth that India is going to witness over the next five years." However, can India, which has taken the opposite approach in the opening-up of digital economy, really achieve a rapid development of its digital economy?

In 1998, when global cross-border digital transactions were still at an embryonic stage, WTO members collectively decided to suspend tariffs on cross-border data transfers until a formal agreement was reached. More than 20 years later, it has yet to emerge. The reason is that, along with the expansion of digital economy in size and content, the "digital gap" between countries is widening. Countries are following their own interests and timetables in promoting the liberalization and facilitation of digital trade , and the possibility of reaching a common agreement in the short term is becoming increasingly slim.

Under this circumstance, some economies that are already at the forefront of the digital economy formed a small group under the WTO framework to strengthen global governance of the digital economy. They have been in constant discussions on key issues of the digital economy since 2017 and are expected to reach an agreement this year.

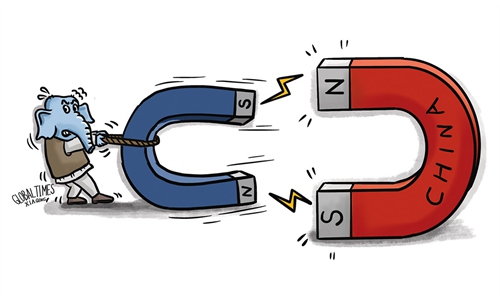

The membership of the group has expanded from 71 to 86 in over four years, including the US, the EU, Japan, China and others. But India has refused to join and some of its practices in the digital economy are clearly at odds with the direction of the international negotiations. In e-commerce, for example, India has been quite slow to open up to foreign investment and its policies have been volatile, largely because of political pressure from small domestic retailers.

However, as the fastest growing and competitive outsourcing service provider, driven by information technology, India is increasingly conservative in opening-up and cooperation on the digital economy. In 2020, India even banned hundreds of Chinese apps under baseless security concerns.

Behind these protective moves, India has an alleged goal of boosting domestic industrial growth. But, will it work? According to the Annual Report on Development of Global Digital Economy (2018) released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, India ranks 22nd overall out of 50 countries. In terms of the size of the digital economy, the US retained the first place with $11.5 trillion, accounting for 59.28 percent of its GDP. China came in second with a total of $4.02 trillion, or 30.52 percent of its GDP. As for India, its digital economy was only about 20 percent of its GDP. In terms of the digital infrastructure and digital innovation capabilities, India was further down the list on the bottom 10 economies.

In 2020, India, together with South Africa, submitted a report to the WTO, where it explicitly opposed the WTO's extension of tariff exemptions on data transmission.

New Delhi's protectionist attitude extends beyond the digital economy. Since the Modi administration came to power in 2014, India has argued that trade liberalization and facilitation arrangements around the world are weakening the policies of developing countries. It insists that developing countries have every reason to demand a timetable for trade liberalization that is incoordinate with developed countries. Holding this principle, India did not sign a single agreement on trade liberalization in the past seven years, regardless of trade negotiations under the WTO or regional trade arrangements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

But can traditional trade policies really protect a country's digital industry by blocking digital transmission? The experience of various countries, as well as India's history since independence, show that protectionist policies are always a double-edged sword for a country's industrial development. Moreover, even the US is emphasizing the principle of reciprocity and it is a question of how many countries would be willing to give unequal opening treatments to India.

The article was based on a commentary written by Liu Xiaoxue, an associate research fellow at the National Institute of International Strategy under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn