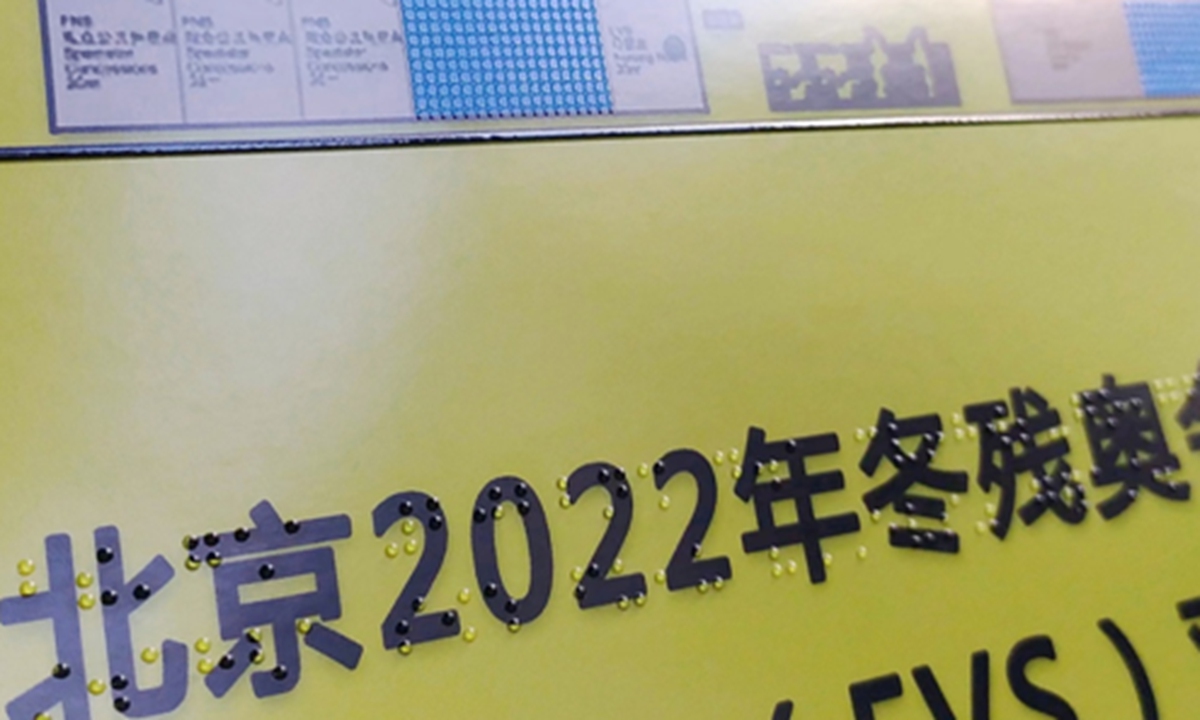

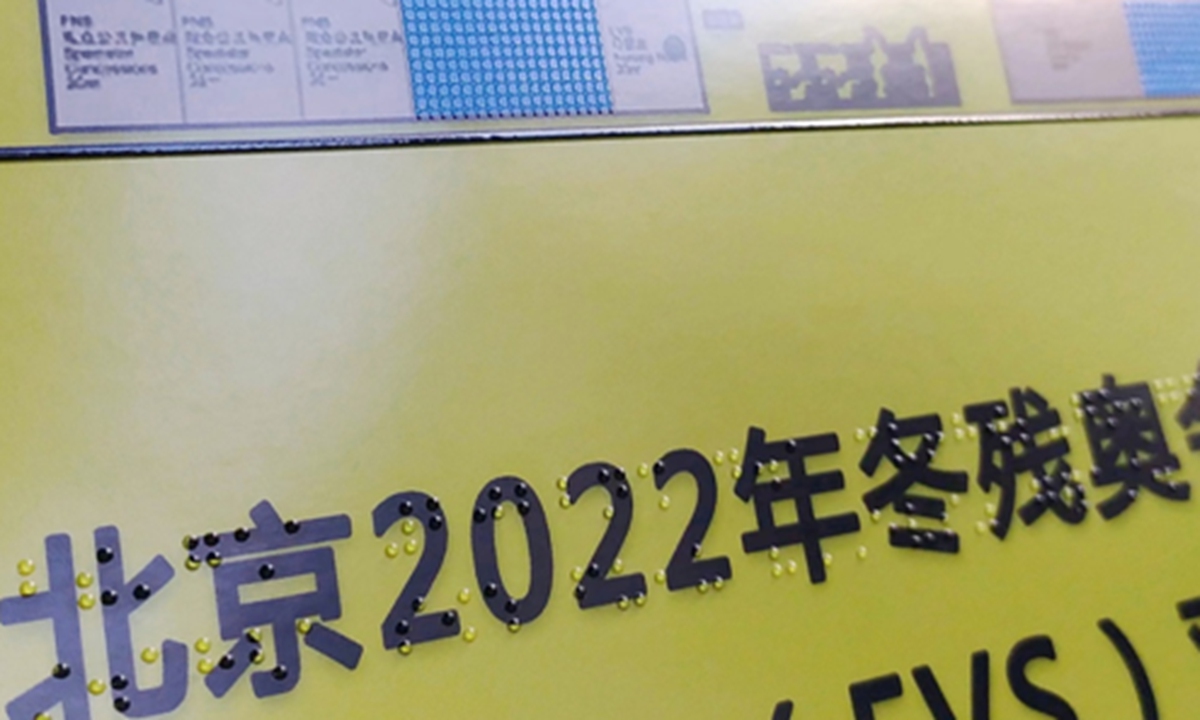

Braille in the Beijing Winter Paralympic Games Photo: Courtesy of Song Yanlin

The upcoming Beijing 2022 Paralympic Winter Games will use an energy-efficient printing technology for the Braille version of the manual for athletes and officials, spectators' guide, venue introduction and maps. It's the largest use of Braille in the history of the Winter Olympics.

Song Yanlin, a scientist from the Institute of Chemistry at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, whose team developed the green printing technology for Braille, told the Global Times on Tuesday that the Paralympic Winter Games serves as a window to show the world China's technological development and progress, especially in caring for people with disabilities.

Song's team printed the spectators' guide for the Beijing Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, service manual for athletes and team officials, introduction book for the National Biathlon Centre and inspection terms for anti-doping, which have large-print and Braille versions.

The introduction, maps and spectators' guide in the large-print and Braille formats were posted at the ticket-checking point of the National Biathlon Centre in Zhangjiakou, co-host city of Beijing 2022.

According to the Beijing Organizing Committee for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, the fundamental purpose of holding the Paralympic Winter Games is to promote an inclusive society that integrates people with disabilities and those without.

The organizing committee highlighted the importance of technology in building a barrier-free environment. Beijing 2022 provided sign language commentary services using an artificial intelligence image in a bid to help people with different degrees of hearing loss.

The green printing technology for Braille has been described by Song as "revolutionary," because it is energy-efficient and low-cost, and allows Braille to be printed on more materials, including paper, glass, stainless steel and pottery, which will last longer than conventional printing, Song said.

He said the conventional process for Braille printing is 15-20 times more expensive than ordinary books, as Braille has to be printed on special paper. The dots easily become flattened by touch, so they don't last long.

Chinese scientists use antibacterial nanomaterial that is able to form a film after penetrating the surface of the paper, and it firmly attaches to the paper so that dots printed through the material are abrasion-resistant.

The green printing technology also allows Braille text to be printed along with Chinese or text in other languages so that the book can be read even by people with visual impairment, Song said. The green printing technique for Braille has been adopted by nine cities and provinces including Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin.

Children at the Beijing School for the Blind started to use Braille books printed with the green technology as early as 2018. In East China's Zhejiang Province, Braille documents and community maps are posted at the entrance of residential communities. Shanghai subways provide direction information for people with visual problems using the green printing technology.

Next, Chinese scientists plan to use the printing technology on food and medicine packaging, so that people with visual impairment can learn expiration dates and read medication guides, Song said.