US human rights

Washington's human rights strategies emerged as a potent ideological weapon after the Vietnam War, having little to do with meaningful human rights - and everything to do with furthering America's global reach.Previously, US leaders never much invoked human rights. A still segregated America obviously made the US highly vulnerable to any human rights strategy and a fierce anti-communist ethos seemed more than sufficient. But after Vietnam and after Nixon's real politick amoral strategizing, Washington was desperate for new ideological weapons to cope with its tarnished image at home and abroad. This "human rights business," senior Carter officials made clear, was to become the very centerpiece of efforts to restore America's post-Vietnam, post-Watergate image

To do this Washington carefully considered how to interact with the newly emerging US human rights organizations. Appalled by Cold War rationales and tactics that came to light in the Vietnam war era, (overthrowing regimes, assassinating leaders, training torturers, supporting dictatorships) leaders of the public rights movement sought to infuse Washington's policies with a human rights idealism just as Washington sought to fashion a rights-based universalistic, individualistic vision of America to support its resurgent global aims. As President Carter said, "Human rights is the soul of our foreign policy." Human rights leaders agreed.

The Carter administration's efforts to develop an "international rights regime" show just how directly Washington used human rights for strategic political purposes. In 1977, Zbigniew Brzezinski set forth to President Carter the reasons for setting up a "human rights regime." What was needed was a "solid intellectual base;" research was also needed to encourage "the varieties of human rights" and their promotion in "diverse social and cultural contexts." But if such approaches were seen as solely government-inspired, they would not be sufficiently effective. So it was necessary to nourish and spread the concepts via the "echo chamber" of foundations, academia, existing organizations, and international groups. In short, Washington wanted US human rights organizations set up and their roles expanded; they wanted to see reports published on human rights abuses and political prisoners. If the cost was sometimes accepting a range of often fierce (but narrowly focused) criticisms about some American actions, it was a burden they had to bear.

It proved an effective symbiotic dynamic. Of course, the movement's leaders noted, Washington itself committed some terrible human rights violations. Indeed, they spent a good part of their time describing them. But when US "mistakes" and egregious acts came to life, human rights leaders began "shaming" Washington into changing its ways, reminding it that America's preeminent power was exceptional in the ways it embodied humanity's great ideals, ideals that legitimized its role as the foremost champion of human rights.

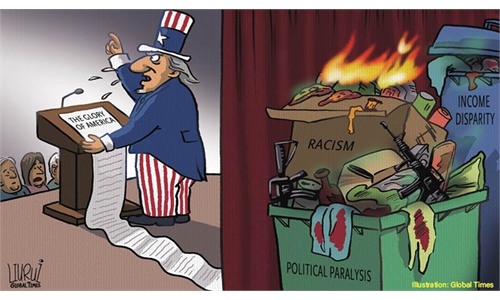

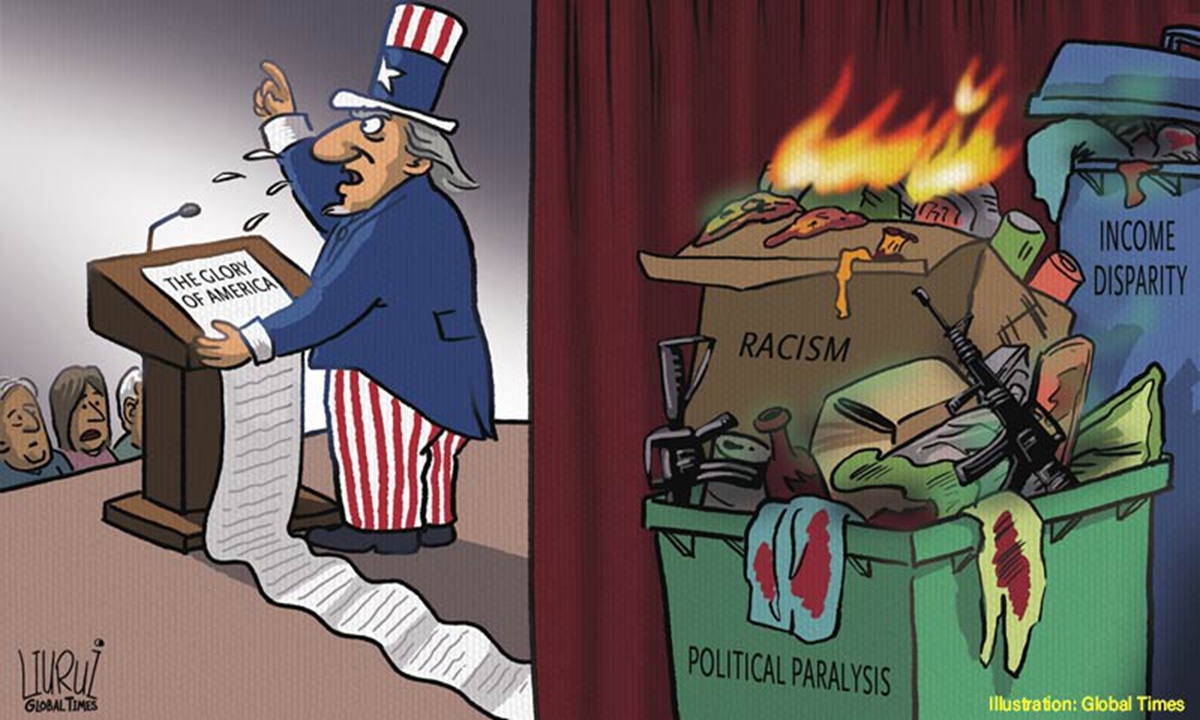

Notable implications followed: First, if human rights abuses were committed by various non-Western nations, they were said to expose the sordid and undemocratic nature of those societies within. By contrast, abuses within the US were aberrant - a reflection of an America not living up to its ideals. Thus Vietnam was aberrant, a "mistake." No examination of systemic flaws in the US was required. Such a divide allowed human rights to become a weapon against entire societies and cultures - focusing on specific issues but in a way that pointed to the sordid, even evil, character of regimes toward which the US often focused its "war of ideas." In this way, "regime change" could become part of a highly politicized US strategy as the US promoted itself as the paragon of human rights and democracy.

Second, this idealized vision worked to polarize and turn against each other various aspects of humanity's progressive traditions both within the US and abroad - dividing needs and rights, individual and collective interests, reform and revolution, equality and freedom. This allowed for little focus on humanity's overwhelming social and economic needs, attacking methods of confronting such needs as a violation of US-proclaimed "universal political rights."

Third, human rights language was not to be part of US domestic political discussions. It was tied to foreign policy debates that allowed America to judge the actions of other nations. From its inception, it was separate from any systemic examination of US power. That was reserved for others.

Finally, the resurgent idealism of human rights organizations effectively repressed what America's war against Vietnam was about. As a consequence, the organizations later took no stand on US aggression, arguing that it could not be defined (as is evident in their failure to take a stand on the invasion of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Panama to name a few). They took no stand on the strategies of "nation-building." One looks almost in vain for accounts that show how US power has long sought to dominate a global system completely open to its economic and political penetration in ways that stand against the efforts of countries throughout the South to find their own independent ways to develop.

The author is a US scholar and Adjunct Professor of History at New York University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn