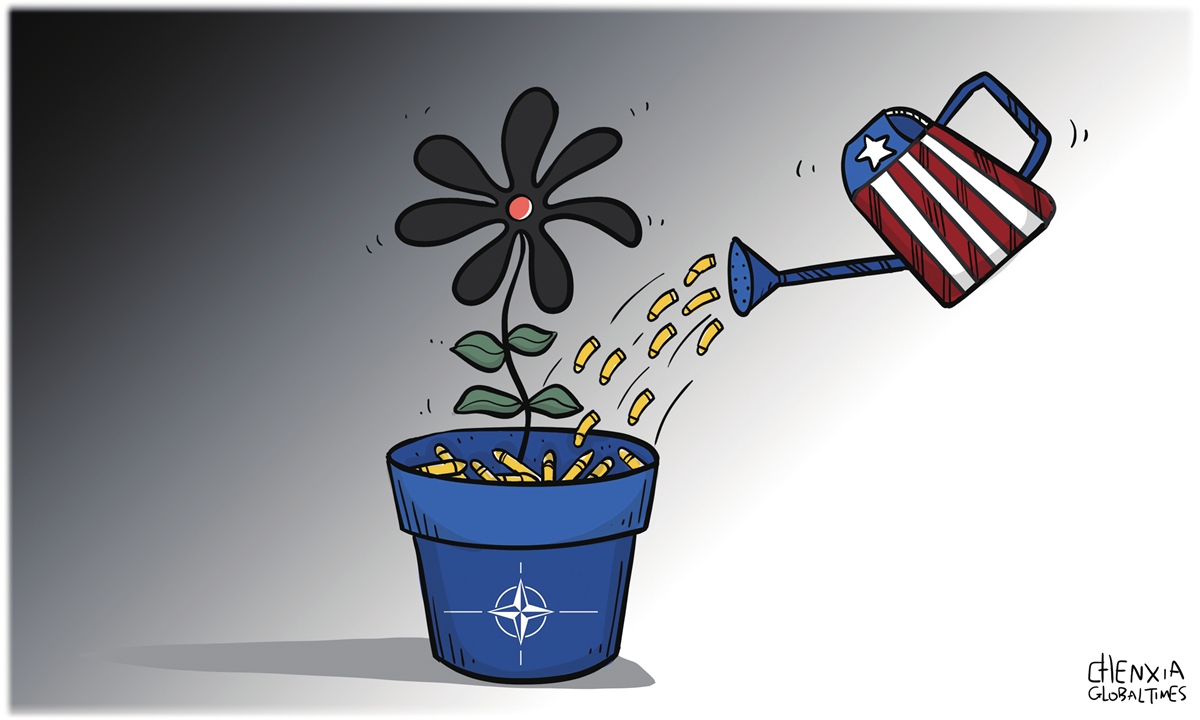

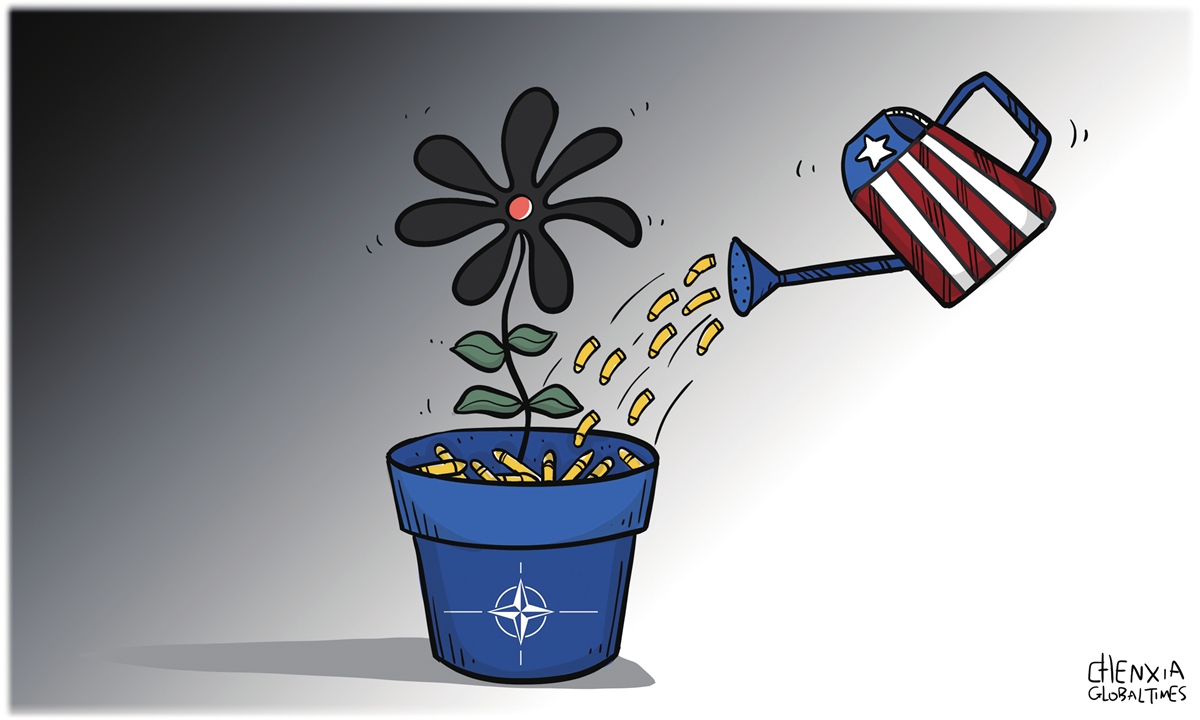

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Click here to stay tuned with our live updates on Ukraine tensions. The Russia-Ukraine war is both a natural consequence of the dramatic geopolitical changes in Europe in the wake of the Cold War and the nature of NATO - the world's single most powerful military bloc.

NATO consists of a total of 30 countries in Europe and North America, most of which developed ones. Its military expenditures account for around 60 percent of the entire world's defense spending.

Because NATO is a military bloc, it prepares for war and is bound to have an enemy. That enemy during the Cold War was the Warsaw Pact, led by the Soviet Union.

Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty clearly establishes the principle of "collective defense," which means that whenever one or more NATO member countries are attacked or invaded by an external military force, it can be considered an attack or aggression against all member countries, and the military forces of other member countries are obliged to aid in defense or retaliation, without the need for authorization from national governments anymore.

After 9/11, NATO countries invoked Article V for the first time and supported and participated in the US military strikes against bin Laden and his terrorist organization.

When the Cold War ended, the Warsaw Pact disintegrated. But NATO remains intact, and it is always looking for a "grip" to continue to survive and thrive.

First, it has tried to transform itself into a values-based political alliance, and then it came up with "new concepts" to justify NATO's global military intervention in response to the changing global security environment.

Central and Eastern European countries like Poland, Hungary, and Ukraine also need NATO's continued presence out of concern for their own security.

Following the end of the Cold War, the US and Europe knew if they couldn't rope Russia to their sides, they would be unable to regulate it and Europe would not feel secure. Therefore, some NATO experts suggested that the most desirable goal of NATO's eastward expansion is to integrate Russia into the European system after completing its "evolution," making Europe a permanent haven of peace.

But they forget that NATO was not created to unify all of Europe through cooperation, but only to check the Soviet Union and its former allies with the help of strong military power. In essence, NATO was to bring Russia down as it did to the Soviet Union. So how could such a military bloc be used to pull Russia into their paradise?

US-Russia relations also dictate that such a vision can only be an illusion.

I visited Poland in 1996. At that time, Poland was actively seeking to join NATO. A professor at Warsaw University reminded me of two things. First, that joining NATO was about getting a "green card," while joining the EU was about "naturalization;" and second, that they had not forgotten that it was the Americans who helped them finally achieve "back home."

In 1999, I witnessed the flag-raising ceremony at NATO headquarters for Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary to join NATO.

A small incident happened that is still interesting to think about. Before Poland became a full member of NATO, the Polish ambassador sat next to the US ambassador as an observer at every major event, but after Poland became a full member, the Polish ambassador's seat was moved alphabetically between the Norwegian and Portuguese ambassadors, thus becoming distanced from the US ambassador. "I will think of my old friends," the Polish ambassador said meaningfully.

When NATO "integrated" some former Warsaw Pact members under Soviet control, it moved closer to Russia geographically. These moves were bound to increase Russia's fears of geopolitical change.

The outcome of this ongoing Russia-Ukraine crisis, regardless of who wins, will increase the raison d'être of NATO as a military bloc and strengthen and expand it. The Russia-Ukraine war shows that the Cold War is really only half over and the second half just starts.

The author is a senior editor with People's Daily, and currently a senior fellow with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China. dinggang@globaltimes.com.cn. Follow him on Twitter @dinggangchina