Japan must fix domestic human rights issues first

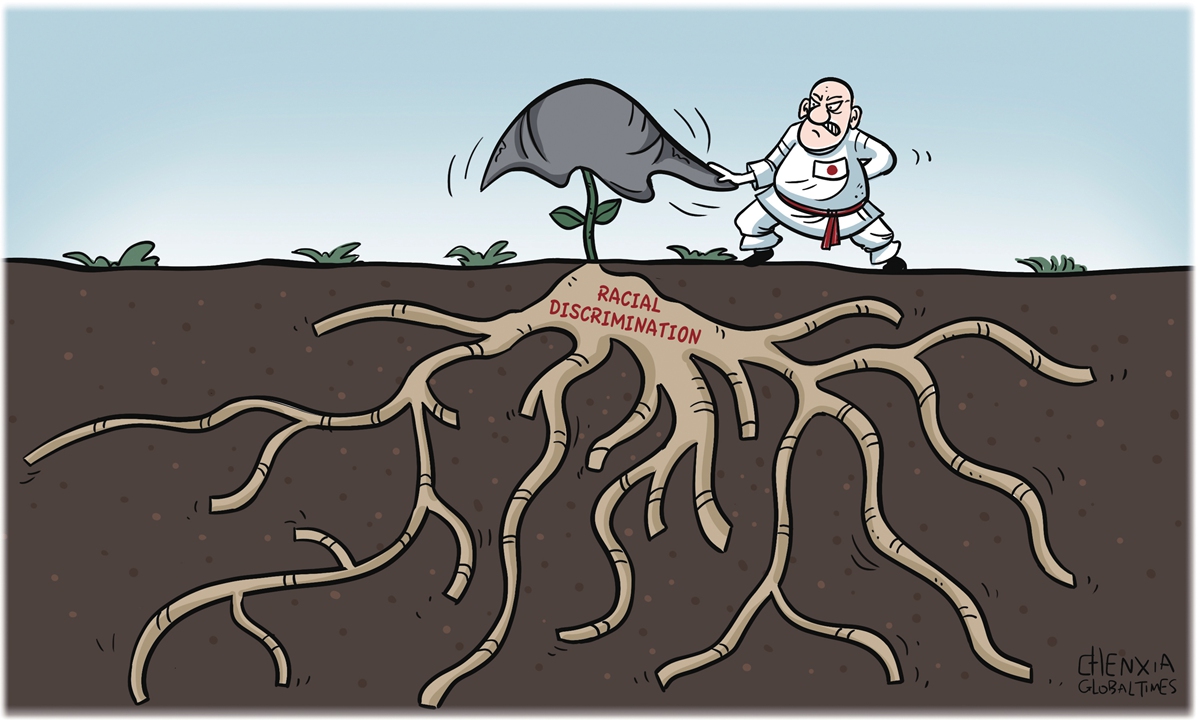

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

In recent years, the Japanese government has focused on "human rights" in its foreign policy, and some Japanese politicians with extreme ideas have followed the US and hyped up the topic for political purposes, unilaterally glorifying Japan's own human rights approach. In fact, because of the long-existing serious problems in Japan, the country has been repeatedly admonished by relevant UN agencies and is subject to frequent public protests. The international community and even the Japanese public considered the country to have performed poorly in terms of human rights.

Ethnic and racial discrimination has long existed in Japan, with a resurgence of related incidents. The Japanese government takes a conservative stance on this issue and claims the country to be a "mono-ethnic nation," ignoring or even denying the existence of other ethnic groups. This has led to conflicts.

For example, the Ainu people have lived mainly in Hokkaido for a long time, but their status as indigenous people was not officially recognized until the early 21st century. The government's policies for the Ainu were labeled as "protection and assistance," but in reality were more indicative of forced assimilation, resulting in the shrinking of their population and discrimination in education and employment.

Although Japan ratified the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1979, the Japanese government refused to recognize the status of the Ainu people as an ethnic minority and indigenous people on the grounds that "Japan is a mono-ethnic nation" despite several reminders from the UN Human Rights Committee. After a long struggle by the Ainu people, it was not until June 2008 that both houses of the National Diet passed a resolution officially recognizing the Ainu as indigenous people and the myth of a "mono-ethnic nation" was finally broken in terms of law.

However, in Japanese society, especially among the conservative political elites, there is the "mono-ethnic" myth and the denial of Ainu people as indigenous people. For instance, Taro Aso, then deputy prime minister of Japan, claimed that "no country but Japan has lasted 2,000 years with one language, one ethnic group and one dynasty" during a gathering in his home constituency in Fukuoka Prefecture in January 2020. He was immediately protested by the Ainu affiliated groups and apologized just one day after that statement.

On March 12, 2021, NTV, one of the five major commercial TV stations in Japan, aired a program using a pejorative word - to be precise, the word "inu" which means "dog" - to refer to the Ainu people, causing a public outcry. Despite the apology of NTV and the program's producers, the case revealed the discrimination against the Ainu people.

In addition to the Ainu, the Ryukyu people, who live mainly in Okinawa, are also distinctly different from the Yamato people on the main islands of Japan in many aspects, such as social culture and lifestyle, and they have long strived for greater autonomy. Since 2008, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has repeatedly recommended in its reports that Japan recognizes the Ryukyu people as indigenous people and increases its efforts to protect their rights. But the Japanese government has so far refused to do so. Instead, some conservative politicians accused the UN's advice as being intent to create national division in Japan.

Foreigners in Japan have long suffered from unfair treatment. Due to the long-held "mono-ethnic" myth, Japan has been closed and conservative in its immigration policy. There are inequalities in education, employment, livelihood security and political rights between foreigners and Japanese citizens. Foreigners are often treated unfairly in terms of rental housing, working conditions and social security, even though Japan is in urgent need to bring in foreign labor due to the aging Japanese population.

In addition, some foreigners in Japan's Technical Intern Training Program have to deal with harsh work conditions despite limited benefits. There are even cases of bullying and discrimination against foreign interns. Although an act came into effect in 2017 to protect these people, an effective and adequate monitoring mechanism for law enforcement is still badly needed.

Besides, even those apply for refugee status in Japan have to undergo the process of detention and investigation that is nontransparent and prolonged. During that process, injury and even death of detainees happen from time to time. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has adopted several admonishments to touch on this very serious issue in Japan.

The violation of Japanese laws by US military personnel stationed in the country has long become an important human rights issue for the locals.

Frequently, US soldiers stationed there committed crimes, including rape and murder, in Japan. Yet, according to an agreement between Tokyo and Washington, US military authorities have the primary right to exercise jurisdiction over members of the US army. This has made it difficult for the Japanese judiciary to intervene in the cases and to fully protect the rights and interests of local residents, resulting in strong dissatisfaction and protests from the Japanese public.

And during the COVID-19 epidemic, US troops in Japan would usually disregard local epidemic prevention and control measures. This has endangered Japan's anti-epidemic efforts.

It is absurd how different foreign groups can be treated in Japan: On the one end, discrimination and suppression; and on the other, overprotection.

Human rights are a sign of the progress of human civilization. Japan needs to pay more attention to and improve its own human rights situation. It has to effectively and efficiently solve its human rights abuses. If a country does not take its human rights problems seriously but points its finger at others based on political manipulation, it won't be taken seriously.

The author is an associate professor at Nankai University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn