James Peck Photo: Courtesy of Peck

Editor's Note:The escalated conflict between Russia and Ukraine does not just expose problems between the two countries. It also reveals the realities of other major players in the global geopolitical arena: China, the US, and Europe… How will the ongoing Ukraine crisis end? What should Europe learn from it? Is it possible for China and the US to join hands to resolve the crisis? Global Times (GT) reporter Xia Wenxin discussed these topics with James Peck (Peck), a US scholar and adjunct professor of history at New York University. He recently did an interview with GT on former US diplomat George Kennan. Check out the interview here.GT: What do you think about the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine? Why did Russia and Ukraine, two "brotherly nations," come to war with each other? What role do the US and Europe (especially its NATO members) play in the escalation of the conflict?

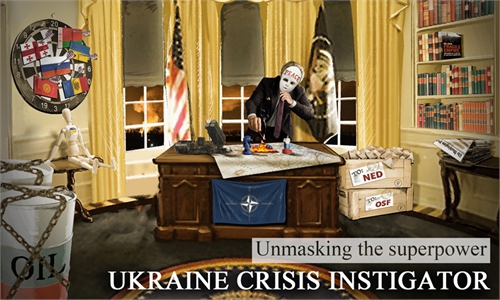

Peck: The crux of the Ukrainian crisis goes back to the refusal of the US and NATO (and the EU) to support an independent, neutral Ukraine that did not threaten Russia. George Kennan and other critics had warned where things were headed long before 1997 when Kennan made his prophetic statements. NATO's enlargement in 1999 and then again in 2004 made all too clear Washington's underlying agenda. First, to significantly cripple Russia's long-term influence. Second, to further entrench US power at the heart of an expanded NATO, one less challengeable by some French and German leaders concerned over the continued US domination of the alliance. Analysts have highlighted the refusal of the US to negotiate the basic issues with Russia and the all too obvious escalatory actions taken over the years by the US in Ukraine - from "democracy promotion," "the Orange revolution," the massive funding, the training and arming of Ukraine forces, etc. It's an extensive list, as analysts like John Mearsheimer have argued. The bottom line is that Washington and a still largely US dominated NATO showed a consistent refusal to be conciliatory toward Russia's deeply felt and understandable security needs. The arguments that George Kennan made so many years were no longer heard.

Europeans sometimes say they are now pursuing a "values-based" foreign policy. If so, they have yet to articulate how this really fits with the US insistence on being the preeminent global power. President Biden's Warsaw speech, with its remarkably strident rhetoric, depicted a period of near endless international strife: "A battle between democracy and autocracy. Between liberty and repression. Between a rules-based order and one governed by brute force. In this battle, we need to be clear-eyed... We need to steel ourselves for a long fight ahead."

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian crisis testifies to the all too familiar US geo-political calculations and rhetoric that fuel global tensions that could often have been managed without escalating into crisis. Of course, there are powerful US military and security forces, along with various domestic political forces, who profit from all this as they argue that the very conflicts the US often aggravates require them to have ever larger budgets to cope with them.

GT: Do you think the Ukraine crisis will take a "dramatic turn"? For example, if the US promises not to allow Ukraine to join NATO, will Russia immediately withdraw its troops?

Peck: It is hard to say where this is headed. If Washington could put itself in Russia's position for a moment, knowing it would never tolerate such forces or foreign presence on its borders (or the Caribbean - or just off its coastal waters), it would suggest the obvious - a neutral Ukraine not in NATO, its independence guaranteed by all powers, no offensive weapons in the country. Even then, Ukraine would have an extremely hard road ahead of it. The severely damaged country has bitter divisions that will not be easy to manage. The Eastern regions have to be given at least a viable, guaranteed autonomy or perhaps some more creative form of protection.

Yet the dangers of a long-term war are considerable - and while European leaders, in this first greatly influenced social media war, are strongly supportive in public, there are growing concerns over the war and the growing risk to their countries and their economies. The terrible ways this crisis could escalate are finally starting to sink in ways that will help fuel ways to end it. The way out and how to do so is possible if the reasons for how it came to this state are really understood.

GT: Should Europe learn something from the current situation? Does it need to reflect on its strategies or decisions?

Peck: The Europeans should think about why they were so against working to make Russia part of a Common European home or cooperating with President Putin in his early attempts to join Russia in a cooperative way with NATO. Unless Europeans are willing to seriously consider the implications of Washington's global preoccupations and how Europe fits into them, they are likely to remain where George Kennan said they would end up long-term again - once again unable to get out of a militarized dynamic that works against a more peaceful Europe. Where Washington is going amidst its own deepening governance problems is anyone's guess. But unlike former days, when mobilizing against an "enemy" often brought an ersatz sense of unity in prosperous times, those days are a thing of the past. Once, the US could afford massive military expenditures, constant wars, and still have relative economic well-being for a majority of its citizens. No more. The domestic implications of this are unclear, but they are not to be underestimated, particularly if serious global economic problems erupt that the war has further aggravated.

Europeans can hardly be confident that Trump or a Trumpian Republican won't be in the White House after 2024. In addition, state to state relations in Europe still have underlying tensions. Europeans have yet to show what role a confident, relatively autonomous Europe might play in the world. Indeed, in various ways, their actions in Ukraine reflect a falling back into some of Europe's less admirable ways from its centuries-long war strewn past.

A notable aspect of this crisis is how the Europeans and the US ("The West," as the American media likes to repeatedly say once again) applied such sweeping sanctions against Russia, all the while pressuring (and certainly not consulting) other nations who are being seriously affected by them. Washington and the Europeans may not like to see how "the West" is once again unilaterally prioritizing its interests over others, but those in the rest of the world certainly see this is the case.

All this is to say that a Europe pursuing a more independent, less aligned way offers a more positive global role, one where Europe could boldly pursue climate and nuclear issues and innovative issues of global governance rather than being drawn into the long-term remilitarization of Europe or perhaps even worse - accepting Washington's urging to expand its military role into Asia.

GT: Do the differences between the US and China outweigh their common interests? Is it possible for the two countries to work together to resolve the Russia-Ukraine conflict?

Peck: If the US shows a degree of flexibility and tones down its rhetoric, then yes, there is much these two countries could do to help resolve the crisis. But, of course, this requires that the United States, not China, change course to a considerable degree. So far, the US has not done so, and President Biden's remarkably histrionic rhetoric in Warsaw may now expose him to harsh attacks in the US for not standing firm if any reasonably fashioned settlement comes into being.

Still, it should be remembered that there are Americans and Europeans, and they will surely increase, who realize that the kind of foreign policies that lead to Ukraine will bring neither a more peaceful world - nor one sufficiently capable of effectively coping with global warming and the threatening existential crises that requires innovative ways of global governance rooted in a sense of justice - ones motivated by a very different spirit than the US and NATO showed towards Russia from the early 1990s on.

GT: Do you think there's still a chance that China-US relations will change significantly under the Biden administration?

Peck: There is some possibility the Biden administration will change aspects of its policy towards China even though most indications suggest an increasingly tense and fraught relationship. The Biden administration is massively increasing the defense budget, has taken provocative steps regarding Taiwan, is trying to mobilize its traditional allies to join its military strategies against China (AUKUS, the Quad), is continuing Trump's efforts to weaponize US trade policies and seeks to use the sanctions against Russia as part of an effort to "de-couple" the Chinese and American economies. All these, of course, are just recent efforts that need to be set within the context of how unsettling China's historic rise has been for the US in all sorts of ways.

So in that sense, the picture is grim. But setting aside possible black swans, here are a few caveats about seeing US policy towards China simply set in stone.

First, this is not a rerun of the Cold War when domestic anticommunist fears blended with demonic depictions of the Soviet Union and China. Yes, US polls reveal a quite negative view of China, but in reality China is way down the list of issues strongly felt by polled Americans. I doubt that many Americans see China as the underlying cause of Washington's increasingly dysfunctional system of governance. The China preoccupation is very much an elite affair and serves key military-industrial interests. It serves as well, those advocating various forms of state economic planning, something Congressional leaders from both parties seek to legitimize in their anti-China rhetoric.

Second, the US political establishment is divided on China. President Biden confronts an increasingly frustrated Democratic party whose progressive wing is becoming deeply disenchanted with the ways his budget and foreign policy agendas clash with their strongly held views on climate change and the diverse domestic reforms they seek.

At the same time, the US corporate elite is also conflicted, though they are not about to publicly question Washington's China policy. For many, decoupling from China in various ways and the Biden sanctions on Russia risk speeding up the weakening of the dollar as the world's reserve currency, something utterly anathema to concentrated financial interests in the US. In private, moreover, some fear the US has lost the capacity to stabilize the global economy on its own when confronted with a future crisis through the operations of the Fed, Wall Street, and vast government deficits. For all the talk among experts about a collapsing China in years gone by, the US has institutionalized, as became evident in 2008, the idea of "systemic risk" into the very heart of its economic operations. Without the actions China took in 2008-09, it's hard to know where the global economy would be today.