Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

During his visit in Japan, US President Joe Biden on Monday rolled out the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), the economic pillar of US' Indo-Pacific strategy and an important tool for the US to conduct geoeconomic competition against China.

The Biden administration hopes to use the IPEF to demonstrate the credibility of the US in promoting its Indo-Pacific strategy. However, facing many challenges, the IPEF may make the Asia-Pacific economy more fragmented, and in the long run is not conducive to maintaining regional peace.

Ever since the Trump administration proposed its Indo-Pacific strategy, the strategy has been criticized for lacking an effective economic policy pillar. The problem roots in the Trump administration's "America First" approach and Washington's growing aversion to "free trade." As The Economist, a British magazine, said, the international economic policy adopted by the Biden administration is a kind of "soft protectionism." The Biden's international economic policy, in essence, is the Democratic Party's version of "America First."

The Biden administration is trying to build an economic pillar for its Indo-Pacific strategy while also taking into account the resistance against free trade among American voters. Under such condition, the Biden administration throw out the IPEF.

First, the biggest problem with the IPEF is that it's difficult to provide practical benefits in terms of market access for regional countries. Developing countries in Southeast Asia and South Asia are looking forward to exporting agricultural products and manufactured products to the US. However, US labor groups, most Democrats and Republicans, have opposed measures such as tariff reductions, arguing that they will weaken domestic employment and manufacturing. This is also the reason why the Biden administration has chosen to stay away from regional trade agreements such as CPTPP and RCEP. In the absence of concessions on tariffs, Wendy Cutler, a former US trade official, argued that the IPEF was "not CPTPP clearly," referring to the regional trade accord that the US abandoned.

Second, under the IPEF, the Biden administration is trying to dominate the rules and standards of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and 5G. The framework also includes arrangements for digital trade. But some progressive Democrats believe the IPEF would increase the influence of tech giants. They worry that the framework will introduce rules that harm the rights of American workers and consumers in areas such as digital trade without the approval of the US congress which will lead to deregulation of technology companies and violate the privacy of the American people. In addition, the rules of digital trade and digital technology that the US wants to promote are too "Americanized," and many countries in the region simply cannot meet the so-called "high standards." The IPEF may become a "club of rich countries," and it will be difficult to effectively help regional developing countries to bridge the "digital divide."

Third, it is difficult for the Biden administration to provide sufficient political and economic capital for the framework. Whether it is this year's congressional midterm elections or the 2024 US election, Biden and the Democratic Party will face severe challenges. The IPEF has not been approved by the US Congress, and its political sustainability has been questioned. In terms of funding, the Biden administration is also stretched thin. Taking infrastructure as an example, the US government has so far not announced how much money it plans to invest in Build Back Better World (B3W). In addition, the support of the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) for infrastructure projects in the Indo-Pacific region is also very weak. Washington has always emphasized that it will promote infrastructure by mobilizing private investment, but few US private institutions are willing to participate in such ventures, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

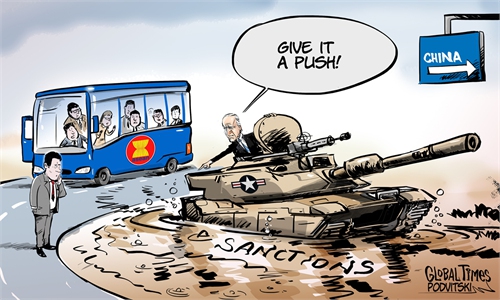

Most importantly, the IPEF, which is driven more by geopolitical considerations than economic factors, excludes China. But regional countries are reluctant to get caught up in the dilemma of choosing a side between China and the US, especially when China is their biggest trading partner. Since the Obama administration, the US has tried to weaken the economic relationship between China and Indo-Pacific countries, which is considered an important foundation of "China's international influence." US strategists say the close economic and trade ties between China and Indo-Pacific countries pose a challenge to US regional dominance. They claim that "China uses economic means to weaken the cohesion of the US alliance system."

Against the background of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, US' "economic war" against Russia is in full swing, and Washington seems to be preparing for an "economic war" against China in the future. The abuse of "national security" reasons by the US has become more and more reckless, and the IPEF may cause artificial disturbance to the stability of regional supply chains. Under the banner of "supply chain resilience," the Biden administration is promoting the formation of a "targeted decoupling" camp in the Indo-Pacific region to reduce the economic dependence of relevant countries on China. Trade relations are conducive to the stability of relations between countries, and regional countries need to watch out for the long-term harm of the US-led decoupling campaign. The weakening of economic ties will only make peace more fragile.

Undoubtedly, the global economy is suffering from multiple shocks such as high inflation, geopolitical conflicts and energy crises, and the Asia-Pacific region is also facing serious threats. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Policy Support Unit released a report on May 20, saying that the region's economic growth in 2022 will slow from 5.9 percent in 2021 to 3.2 percent due to factors such as epidemic resurgence and supply chain disruptions. In this case, what the Asia-Pacific region needs is cooperation rather than fragmentation. The IPEF may not go very far.

The author is a senior research fellow at the Charhar Institute and a China Forum expert at Tsinghua University. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn