Spur policy action

US youths leaving care system are given cash handouts amid COVID-19

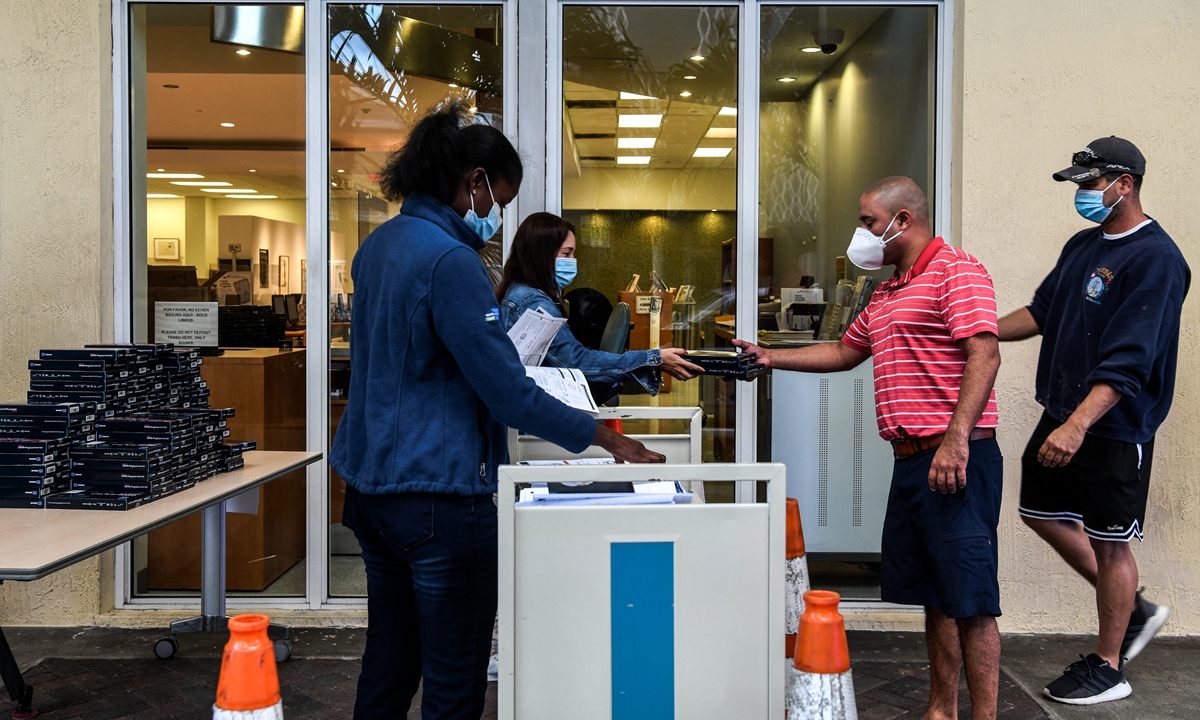

Employees of the Miami-Dade Public Library System distribute COVID-19 home rapid test kits in Miami, Florida, the US on January 8, 2022. Photo: AFP

Like many teenagers in foster care, Korah Loyd dreaded her 18th birthday - a milestone that leaves thousands of vulnerable young people facing homelessness and an uncertain future in the US each year."It was a collective joke among foster kids: When you turn 18, what street are you going to live on?" Loyd, who is now 28 and lives in Seattle, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "You're literally giving yourself up to be homeless."

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred policy action targeting social inequality in the US, and concern about the plight of youngsters "aging out" of the care system has prompted moves to help foster youths shift to financial independence.

The US foster system includes youths placed with relatives, other families and group homes.

California - one of several states to have more recently raised the age for those leaving care to 21, though only on an opt-in basis - has begun cash handouts as a way to cushion the transition to the outside world.

It is helping local jurisdictions give $1,000 a month to foster youths aging out, part of a universal basic income (UBI) program approved by the state in 2021.

The extra money can be transformative, said Marie-Christine Busque, vice president of programs at Pivotal, a nonprofit in San Jose, California, that mentors foster youths.

She cited the example of one young care leaver who had previously been living on $1,100 a month. "You can imagine an extra $1,000 is life-changing - it prevented her from being homeless, allowed her to continue her studies, and now [she] is stably employed," said Busque.

Because they lack parental support, many young people leaving care often need to work while in school more than other students do, potentially delaying or even derailing their graduation, she said.

'Stable income'

More than 400,000 youths have been in the US foster system at any given time in recent years, said the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a nonprofit focused on child welfare issues.

Youths from low-income families and people of color are disproportionately represented in the system, said Jacqueline Burbank, communications director with the National Foster Youth Institute, which advocates on care matters.

"Income is a huge concern," she said. "Often parents can't provide stable housing for their youth because they don't have stable income, or are living below the poverty line."

About 23,000 young Americans each year reach leaving age in the foster system, and the effects are stark, she said.

More than 20 percent become homeless, and a quarter come into contact with the criminal justice system in the first two years - a trend Burbank said is "steadily growing worse."

At a rally in Washington DC earlier in May, campaigners released what they billed as the largest-ever survey of former foster children and others involved in the care system.

The survey from nonprofit iFoster found that respondents think the system is "failing to prepare youth to be independent when they age out," and want transition benefits to be extended.

As the pandemic spurred an array of policies aimed at tackling inequality and keeping people housed, emergency federal legislation was passed to prolong assistance to former foster youths for housing, groceries and other needs up until age 27.

The measures expired in September 2021, and some advocates and lawmakers - including President Joe Biden - are now pushing for some of those to be made permanent.

In April, Biden spoke of the pandemic's "disproportionate impact" on those in foster care, pledging to boost resources for youths leaving the system and proposing to let states support them until age 27, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Advocates have been pushing for such steps for years.

"Having that extra time from 21 to 26 means so much in their development and in their ability to succeed," said Kimberly Hardy Watson, president and chief executive of Graham Windham Services for Children and Families, a New York nonprofit.

Amid budget negotiations set to wrap up by July, Watson and others in New York are pushing for $35 million to extend a model called Fair Futures to all young people aged 11 to 26 who are in or have left the foster system.

The model, which was launched in 2019, connects foster youths with specialists in education, housing, employment and other fields.

It has had some startling results, organizers say, citing as an example a jump in high school completion rates among former foster children from 21 percent to 94 percent.

"This model has meant the difference between many of our youth being able to start and finish college or vocational programs," said Watson.

Reuters