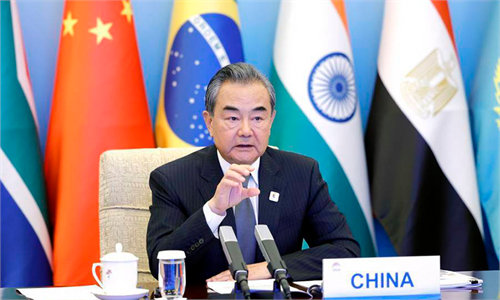

BRICS Photo: brics-russia2020.ru

June is looking more and more like a month for summiteers. In addition to the IX Summit of the Americas to be held in Los Angeles, California, we shall also have the 14th BRICS summit, hosted virtually by China. Argentina has been invited to attend this summit in what is seen as the first step towards formally joining the group. This would also mean that Argentina would be able to join the New Development Bank, the so-called "BRICS bank", headquartered in Shanghai, an entity with a capital of 50 billion dollars.

This is a big step, and only the second time the group has added a new member since South Africa joined in 2009, during the first summit, held in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Indonesia may also be invited to join, thus expanding further this club of rising powers from the Global South, that includes Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. These are countries with vast land masses and populations, and they are called to play a key role in the new century, one marked by the rise of emerging economies and the decline of Western hegemony.

It is often said that the BRICS gave their name to the "decade without a name", that is, the first decade of the new century ( sometimes also referred to as "the naughties"), as it was their signature rise in a period book-ended by 9/11 and the 2008-2009 financial crisis that was most distinctive about those years. With 20 per cent of the world's GDP and 40 per cent of the world's population, they are an entity to be reckoned with.

Remarkably, the group was the result of a branding exercise of a Wall Street banker ( Jim O'Neill, of Goldman Sachs),as he looked for ways to sell bonds by way of assembling various developing nations into one category that might attract investors.

To this day, most readers of Western media will rarely come across stories about the BRICS, but ever since that first summit in 2009, the group has come a long way. The heads of state and government meet every year, and many ministerial and other meetings are held as well. Derided originally by the West as a mere talking shop, the creation of the NDB in 2015, which has lent some 15 billion dollars since then and is well evaluated by credit-rating agencies, put the BRICS into a whole new category.

In fact, in many ways the BRICS are emblematic of the New South that has emerged in the past two decades, very different from the old Third World of yesteryear. Their rise is closely associated with and is part of what the World Bank has referred to as the "Wealth Shift" from the North Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific, and the rise of South-South trade and investment flows to unprecedented levels. The fact that today there are more billionaires in Beijing than in New York City is perhaps the most revealing indicator of this shift. This brings us to what has come to be known as collective financial statecraft, embodied in entities like the New Development Bank and the Beijing-based Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB).

Whereas in the past, developing nations assembled in large groups such as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the G-77, and practiced what was known as the "diplomatie des cahiers des doleances" ( grievance diplomacy) , aimed at requesting massive transfers of resources from the North to the South for what was known as the New International Economic Order, today they have their own banks, and are able to lend to each other.

Joining the NDB would be an important step for Argentina. Saddled with a huge foreign debt, part of which was recently renegotiated with the IMF, Argentina, enormously rich in natural resources and human talent, needs alternative sources to finance its trade and investment projects. The BRICS countries can step in there.

The question has come up as to whether Argentina's joining would mean adding an "A" tom the acronym (and presumably another "I" to represent Indonesia). That would be a mistake. Part of the success of the BRICS lies in its powerful acronym. Other groupings that have followed suit (CIVETS, MIST, BASIC and BRICSAM, among others) have not done well for a variety of reasons, but at least one of them is their unwieldy names. The notion that each new member would demand being added to the name would make expansion impossible.

At the turn of the 20th century, Argentina was among the Top Five richest countries in the world. This was made possible by its association with Great Britain, in those days the world's hegemon, and a country that provided an ample market for Argentine beef, wool and grains. Yet, the 20th century was not kind to Argentina, and the country has endured many ups and downs since its glory days, including several sovereign defaults. It is thus telling that in 2022 Argentina sees its future not in Old Europe or in the North Atlantic, but in the New South, embodied in the BRICS, and whose core is in the Asia-Pacific.

The author is a research professor at the Pardee School of Global Studies, Boston University, a Wilson Center global fellow and a former Chilean ambassador to China. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn