ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Architect tells ‘Chinese narrative’ by absorbing ‘Chinese form’ from salvaged traditional wood buildings

Gateway to the past

Zhu Xiaodi Photo: Zou Zhidong/Global Times

Wooden components on display at the Fayuan Architecture Museum in Beijing Photo: Lin Xiaoyi/Global Times

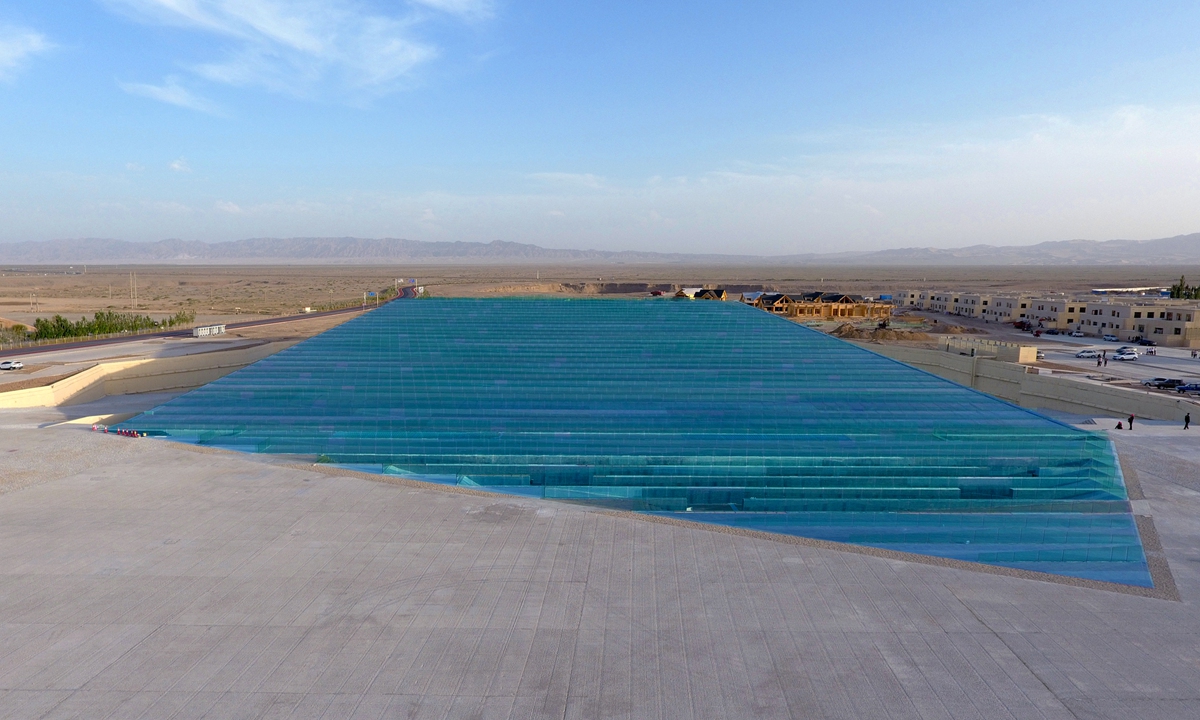

A view of See Dunhuang Again Theater. Photo: Courtesy of Zhu Xiaodi

A dense but staggered arrangement of large arches, columns and brackets resonant with the fragrance of wood in the air, striking the visual and olfactory senses of visitors who enter the Fayuan Architecture Museum.Hidden in the alleyways of Beijing's bustling Qianmen area, the traditional brick and tile courtyard housing more than 100 structural and decorative components from traditional Chinese folk architecture has become a hot topic among literary enthusiasts on Chinese social networks.

Each time a guided tour there has been offered, it attracts many visitors and participants, and calls for an increase in the frequency of guidance offered and more in-depth explanations comes in thick and fast.

"The woodwork collection is a carrier of traditional Chinese architecture and culture. The Fayuan Architecture Museum, where we protect, display, discuss and study traditional wooden architecture, is the dwelling place for my spiritual life. I hope that the museum may also bring visitors solace and inspiration," renowned architect and founder of the museum Zhu Xiaodi told the Global Times.

Entering the public eye

During his work and research in various parts of China after graduating from university more than three decades ago, Zhu, then a fledgling architect, observed that a large number of traditional buildings had suffered from dilapidation of different degrees, or had even been completely demolished amidst a renaissance in modern architecture. Seeing all this lost history, he came up with the idea of collecting all the abandoned, fine, wooden building components he could find.

This marked the start of Zhu's journey to becoming an influential collector, which he stuck to over the years despite relying on a meager monthly salary in the beginning.

Looking back at this journey, Zhu said that he believes that hardships, such as once being knocked unconscious by a beam he tried carrying all by himself and slowly negotiating the acquisition of components by mail in the days before the internet and cell phones, were all valuable experiences that made him who he is now.

As the collection grew, Zhu began to think of ways to create a window through which the public could see and appreciate the collection and learn more about the evolution of traditional Chinese architecture.

"As visitors gaze at this collection, they can imagine how these beautiful components were made and installed, and how these fine pieces caused people to stop and admire them in the past," Zhu said.

Inspired by tradition

The name of the museum came from the book Yingzao Fayuan (Source of Architectural Methods), a salute to folk architectural tradition written by Yao Chengzu during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

There is a common saying in architectural circles in China: "The history of Chinese architecture is written in wood."

Zhu noted that Chinese traditional architecture has a distinctive form, which is based on mortises and tenon joints to mainly make the structure stable. The roof structure includes also complex wooden components such as columns, beams, bracket sets, camel -hump-shaped braces. On the other hand, wooden doors, windows, partition boards and ceilings belong to the category of enclosed components, which creates a consistent spatial atmosphere.

With the technological development of wood carving, some wooden components, for example, sparrow braces, lotus pendants and decorative overhangs, serve a decorative functions, which enhances the feature of architectural art and culture.

In the Fayuan Architecture Musuem, which displays the wooden components of Chinese folk architecture collected by Zhu over the past 40 years from Shanxi, Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong and other provinces, visitors can find the core components that form that most distinctive structural system and spatial atmosphere of traditional Chinese architecture.

At the museum, visitors can see the core components that form traditional Chinese architecture's distinctive structural system and spatial atmosphere.

"No single stroke was repeated in the carving of these intricate components, which tells us much about the woodworkers of the past who devoted themselves to their craft," Zhu said.

Looking back on the development of traditional Chinese architecture, Zhu pointed out that ancient craftsmen used the language of architecture to highlight the beauty and wisdom of Chinese culture.

Zhu noted, for example, that ancient Chinese people designed sloping roofs as concave, curved surfaces rather than straight lines to show the concept of the merger of Heaven and Earth.

"The concept of the unity of Heaven and Man embodies the feelings ancient Chinese had for nature, which is unique to Chinese civilization… Architects hope that the spaces and art forms they create are fascinating," Zhu explained. Inspired by traditional culture, many of Zhu's architectural designs were created with a rational awareness and keen perception toward the natural and cultural environment.

For instance, while designing the theater for a large-scale live performance about the ancient Silk Road, See Dunhuang Again, in 2015 in Northwest China's Gansu Province, Zhu was confronted with the Gobi desert and the splendid historical legacy of the Mogao Grottoes. In response, Zhu used the concept of the preciousness of water in the desert as a metaphor for the importance of the Mogao Grottoes as a world cultural heritage.

Echoing the outstanding blues and greens of the Mogao murals colored with lapis lazuli and malachite, the blue mosaic on the theater's roof and the green glass of the walls reflect each other, symbolizing a desert oasis.

"In the context of contemporary cultural dialogue between the East and the West, we should present a Chinese plan for dealing with the future development of global architectural design," he said.

Zhu said he believes that Chinese architects need to better understand China's long-standing traditional culture. However, they must not stick to simply copying specific cultural symbols, but rather absorb the cultural accumulation behind these symbols, so as to achieve a breakthrough from presenting "Chinese form" to telling a "Chinese narrative."